Naquail Weaver wasn’t expecting to be home with his family for Christmas. The 22-year-old was in East Baton Rouge Parish Prison, held on a $3,000 bail with expectations of a release sometime in early January.

But Weaver got to spend the holidays with his fiancée and his 3-month-old son after students from LSU’s Democracy at Work paid his bond on the morning of Dec. 25.

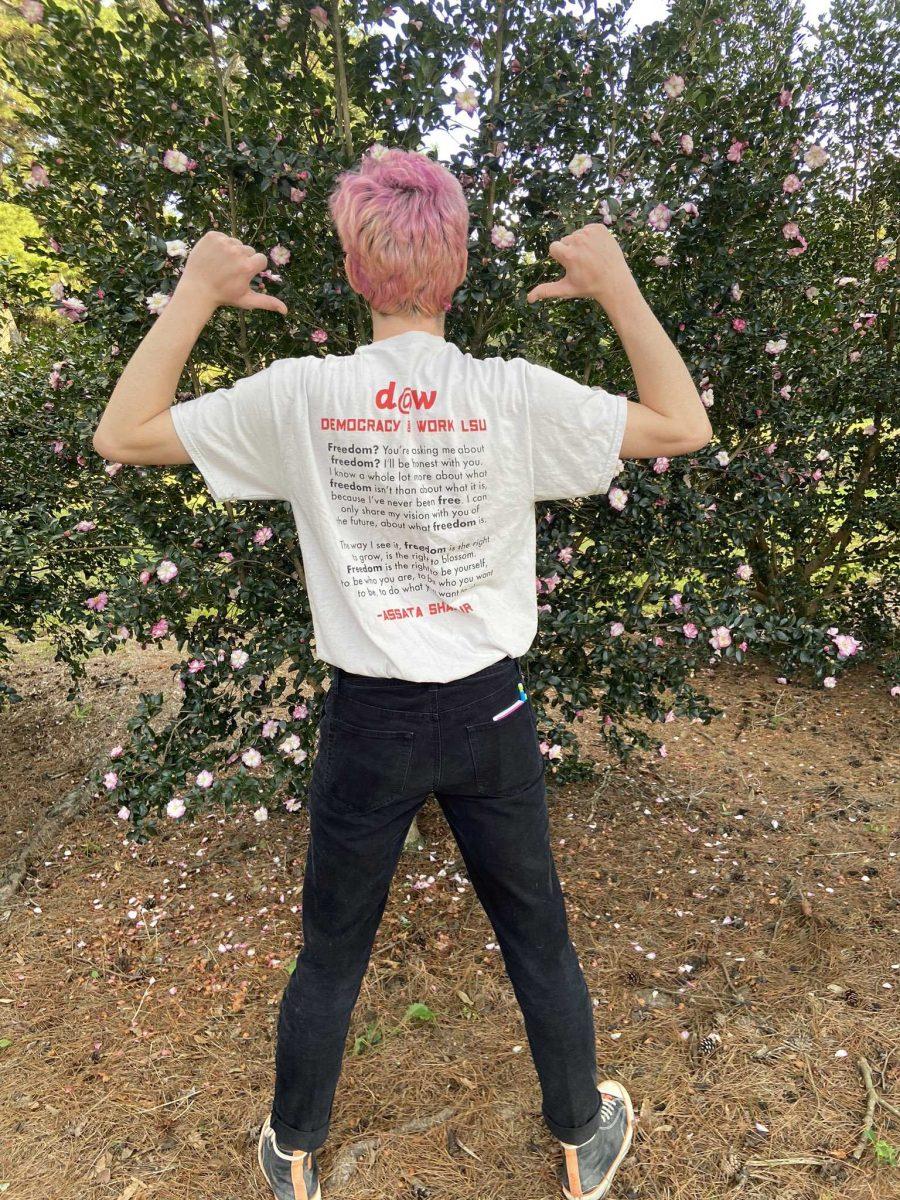

Weaver was one of six prisoners the organization freed by using profits from t-shirts it sold on Etsy.

“Sometimes I still think, ‘I’m not supposed to be home,’” Weaver said. “But God answered my prayers and those people came through.”

LSU Democracy at Work, a student-led grassroots organization, was founded in 2018 and spearheaded other activist efforts, such as advocating to rename 13 University buildings named after individuals with racist pasts.

Democracy at Work member and sociology senior Sebastian Brumfield Mejia said the members came up with the idea after reading Angela Davis’ novel “Are Prisons Obsolete?”

“We developed this bail project because we wanted to not just be reading about these issues but to actually go into the community and address them,” Brumfield Mejia said.

Biological engineering senior and club member Soheil Saneei based the fundraising project on a t-shirt he designed featuring a Malcom X stamp.

“I thought it would be cool to put a stamp of different people that we look up to that have paved the way for activism,” Saneei said.

Saneei originally chose to feature Indian revolutionary Chandra Shekhar Azad on the shirts, inspired by Azad’s work to establish India’s independence from Britain and the fact that “Azad” translates to freedom in both Indian and his language of Farsi.

The design evolved to incorporate photos of other well-known activists and the word “freedom” written in multiple different languages.

On the back of the shirts is a quote from former Black Liberation Army member Assata Shakur: “Freedom is the right to grow, is the right to blossom.”

Saneei said between Twitter and Tik Tok promotions, the organization was able to sell around 370 shirts.

The group coordinated the aunt of Alton Sterling and bail bondsman Sandra Sterling to help them navigate the system. Bond recipients were selected based on bond cost and the crime committed.

“We don’t want to emphasize non-violent crime because the description can be arbitrary, but we also don’t have the capability to make sure that someone who committed, say… second-degree murder won’t hurt anyone,” Saneei said. “We wanted to make sure these people wouldn’t harm anyone.”

What struck Weaver the most was how he was selected out of hundreds of pretrial detainees. He had just woken up and was talking to a family member on the phone when a guard interrupted the conversation and told him he was going home.

“I thought it was a lie, at first,” Weaver said. “They could’ve chosen anybody, but they chose me.”

When Weaver walked through the front door of his house on Christmas morning, he said his fiancée “dropped to her knees” in shock.

However, not all of the former inmates could return somewhere welcoming.

Saneei said three of the prisoners released were homeless and one needed mental care.

The club members, along with Sandra Sterling, helped arrange temporary shelter for the bond recipients.

“It’s not like either option is good – being in prison or having to find temporary shelter or else being homeless – but the people we spoke to were very grateful to be bailed back and did not want to return to the prison,” Brumfield Mejia said.

The group was planning to post bonds for more inmates on New Year’s Eve but decided to focus on expanding its resources through partnerships with other organizations such as the Bail Project, which recently began work in Baton Rouge.

In the meantime, the group plans to continue fundraising efforts and organize meetings with LSU administrators regarding the University’s prison inmate labor practices.

LSU’s contract with the Dixon Correctional Institute, a Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections facility in Jackson, provides the University with around 28,000 hours of prison labor each year.

Inmates can opt to be paid four to 70 cents an hour or work to earn credit toward their release.

“We want to convert that exploitation of labor into a pipeline to a jobs program and a scholarship program, so they can get their time reduced in prison and they’re actually paid for the labor,” Saneei said. “They [should] either have a job opportunity or an opportunity to attend a college that they created so much wealth for… If we could get LSU to commit to that jobs program it would be huge.”

As for Weaver, he hopes this will be the first of many Christmases spent with his son.

“I’ve never had a chance with luck at all,” Weaver said. “I’ve always had bad luck. I’ve never won that route. When they told me they chose me out of 230,000 inmates, I knew that was God at work.”