The skin behind my ears was burning.

I put some tissue paper behind the cutting elastic holding my mask on tight, and that reduced it to a dull ache. I had been sitting for nearly eight hours and had four hours to go before the polls closed. And I was loving it.

Let me explain.

A few months ago, I was reading a news story in The Advocate about how our local election officials in Louisiana were worried about finding enough people to work as poll commissioners — commonly called “election workers” — due to the pandemic. I’d been wanting to do something to serve my community, “even” something small, and volunteered, taking the online test with the Louisiana Secretary of State and contacting the East Baton Rouge Parish Clerk of Court office.

Many other young people had the same idea, and a number answered the call for help. Last Friday, I got a phone call from Fred Sliman, who works for the Elections Department as a spokesman. He had received my application and asked where I wanted to work — anywhere close to my precinct in Mid City, in Baton Rouge, I told him, would be great, nervously adding that I was a newbie at all this.

Don’t worry, he reassured me. The commissioner-in-charge was a veteran and would tell me what to do.

I got a follow-up call on Monday before the election and was told to report to a local elementary school at 5:30 a.m., which I dutifully did. I had flashbacks to my days as a Navy reservist as I walked up Government Street on the cold, predawn morning. Arriving in the midst of organized chaos, I found myself posting signs, pushing voting machines, setting up chairs and tables and then writing down names in a ledger book as a double-check to the voter rolls, as the more experienced — and almost all women — volunteers ran the poll site itself. I saw them handle complicated tasks with grace and confidence. As watchdogs for our representative democracy, they patiently answered questions, solved problems and made everything run with minimal fuss.

As a junior, assistant poll commissioner, I did my best to do what I was told and learn. For instance, I discovered that my handwriting remains truly atrocious — a fact my students can attest to — and that there is an official way to make corrections that doesn’t involve scribbling over the letters again like a little kid.

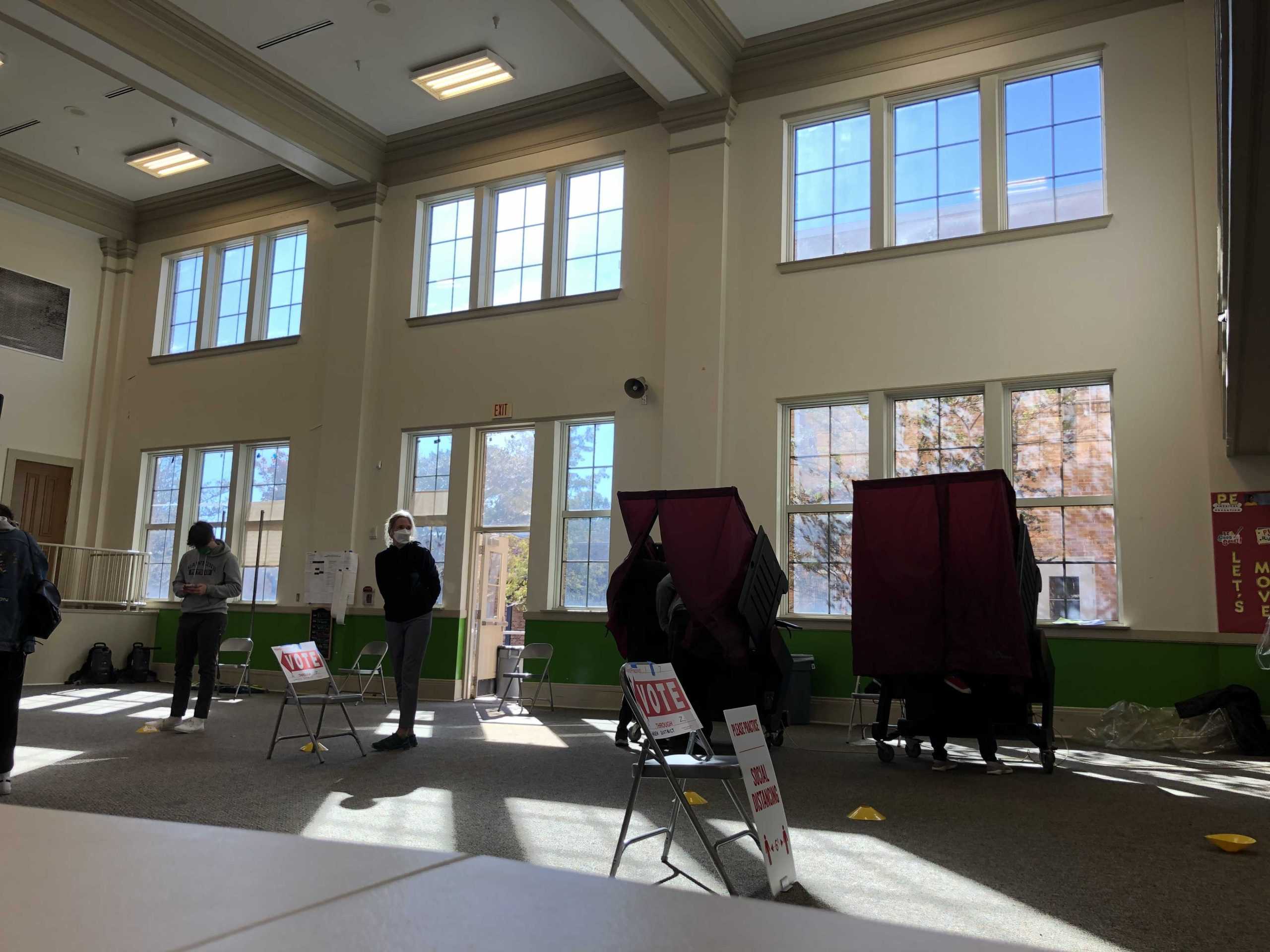

After a busy morning — with hundreds of voters lining up and then successfully casting their ballots, smoothly and safely making it through our precinct’s designated spot in the bright, airy school auditorium — things slowed down a bit. Although there were spurts of busyness, they never caused any real issues. As with many other polling sites, here and across the country, there was less drama and intensity than feared. Many people worked hard to make that happen. It was not an accident.

The pervading air I sensed — despite a couple of exceptions — was one of cautious optimism, patriotism and hope for the future. I saw fellow younger volunteers helping older folks, who had been doing this work for years. I saw parents taking photos of their kids in front of voting booths. I met first-time voters who were in their 20s, voters in their 60s who said they were doing this for their younger friends. I saw people knitting, reading in line and, of course, with this being Louisiana, talking. Talking to each other, talking on the phone, talking to me, the dweeby guy with a pen and a notebook, writing down their middle names, or asking them to spell their last names yet again. There are a lot of ways to spell names. The people behind the names had come from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures and beliefs. And they were nearly universally courteous, kind and civil to one another. While it may sound a little cheesy, in that moment, as an American, I was proud.

Regardless of the outcome, my fellow Americans voted with pride and intelligence, studying their voters’ guides and showing up knowing — and appreciating — their hard-won rights. Whether they voted absentee, early or on the day of, they all had confidence that their votes would be counted, even if took some time.

I saw my neighbors saying “hi,” calling me out by name, behind their masks. I saw people coming straight from or going to their jobs in suits, dresses, coveralls and uniforms, all washing their hands and staying six feet apart. Some parents brought their children. Older teenagers brought their parents. Despite differences, some profound, I saw the best of our country.

“We may not be on the same page,” a fellow poll worker told me, at one point, in a late-afternoon lull, “but we’re better than that.” The “that” she was referring to was the division and even hatred that has come, sadly, to define too much of a local and national politics. But it doesn’t have to define us forever. My own sense of things — as a media historian, who studies other moments of tension and conflict in our society — is that it won’t. It’s a choice. And it’s one that I’m increasingly hopeful for, that we’ll make, together, for the better.

Will Mari is an assistant professor in the Manship School of Mass Communication at LSU.

LSU professor shares experience ‘finding hope at the polls’ as Election Day poll commissioner

By Will Mari

November 4, 2020

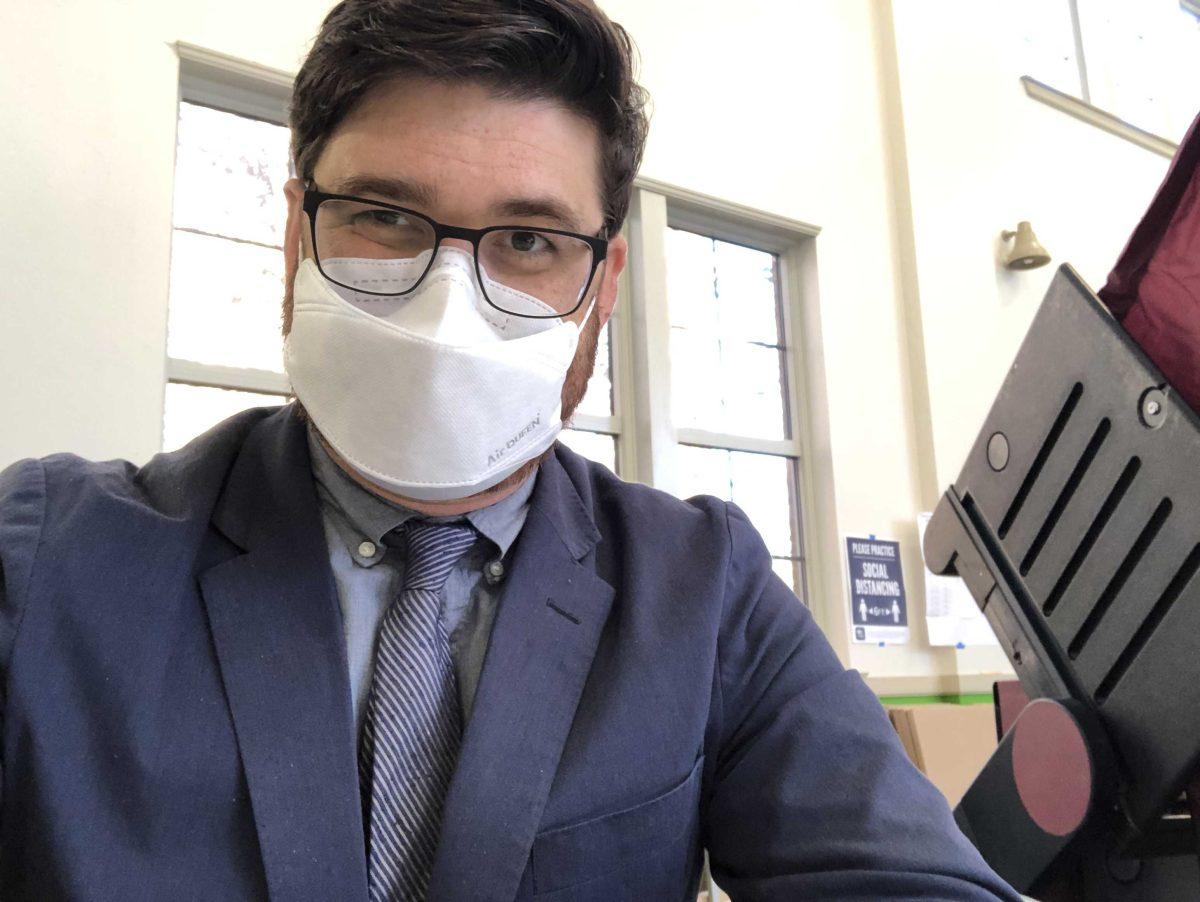

LSU professor Will Mari served as a poll worker Tuesday in Baton Rouge.