For the weeks leading up to Valentine’s Day, I will be reviewing a different romantic comedy movie every week. I am only choosing classics from previous decades that address social issues or offer a unique spin on the romance genre.

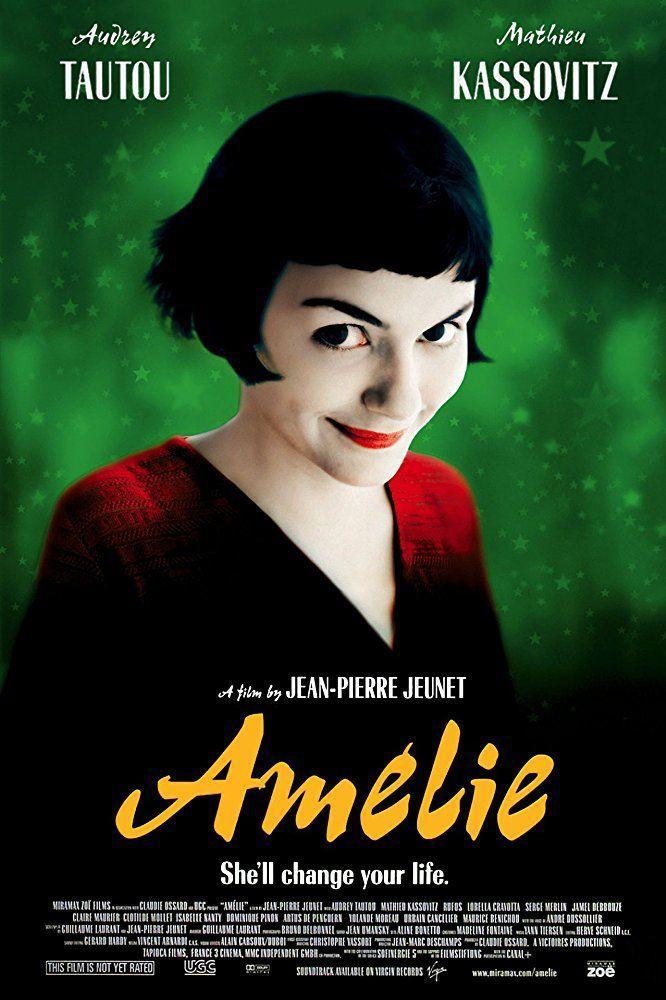

“Amélie” took the French cinema by storm in 2001 and eventually became an international phenomenon. The story about a shy girl who shows kindness to Paris’ outcasts and falls in love with her indisputable soulmate has bewitched audiences for 17 years. The movie inspired a 2017 Broadway musical starring “Hamilton” star Phillipa Soo, continuing to keep “Amélie” alive.

In the movie, Amélie Poulain’s (Audrey Tautou) parents were not her heroes. Her mother died in front of her during a trip to Notre Dame, and her father was a retired army doctor. He wrongly diagnosed Amélie with a heart condition because he seldom interacted with her, so when he did her heart would beat wildly.

Amélie grew up and moved to Montmartre, Paris and got a job as a waitress at the Café des Deux Moulins. When she finds a forgotten box in a hiding place in her apartment, she decides to become an anonymous do-gooder to those in need. She sets up two lonely regulars at the café, visits the man with brittle bone disease across the hall and gets revenge on a particularly bullish grocer.

When a man, Nino Quincompoix (Mathieu Kassovitz) loses a personal book, Amélie makes it her mission to return it to him. She finds herself unwilling to give the book back because that would mean she would never see him again. The two finally meet face to face, already in love, and they ride off into the sunset on his moped.

One of the aspects that makes “Amélie” important is the circumstances following her upbringing. Her parents did not create a healthy environment for their daughter as she grew older — in fact, Amélie was the victim of a neglectful parentage. Her mother died after praying for a son, who would be easier to raise than a daughter. Her father never touched Amélie unless he was giving her a checkup and never ventured far from home due to her false diagnosis.

Once she was old enough to move away, Amélie unwittingly became an advocate for those with disabilities. She pranked the grocer because he would treat his mentally-handicapped assistant cruelly. Her neighbor with brittle bone disease was lonely, so Amélie would visit him. Her warmth touched everyone around her, whether they were disabled or not. She did not discriminate in her acts of kindness.

Most importantly, Amélie exhibited classic signs of social anxiety. Though she did perform kind acts, she preferred to do so anonymously. She never drew attention to herself as she helped people. Subtle hints point to her underlying anxiety, like her reluctance to approach Nino or engage in direct confrontation. Her growth throughout the film shows how those with anxiety can overcome it and let people in.

“Amélie” is a charming, subtle film. The issues the film tackles are not addressed in an obvious way. It takes some thought to uncover the juiciest bits of the movie, but it is one of those rare movies that quaintly discusses issues that are not discussed enough.