Biochemistry graduate student Wendy Hansing was taking her qualifying exam for graduate school at LSU when her water broke. She was just shy of 24 weeks pregnant.

“I have witnesses unfortunately,” Hansing says, recounting how her adviser, the chair of her division and the rest of her committee were all present. Her adviser helped her reach her husband who immediately brought her to the hospital.

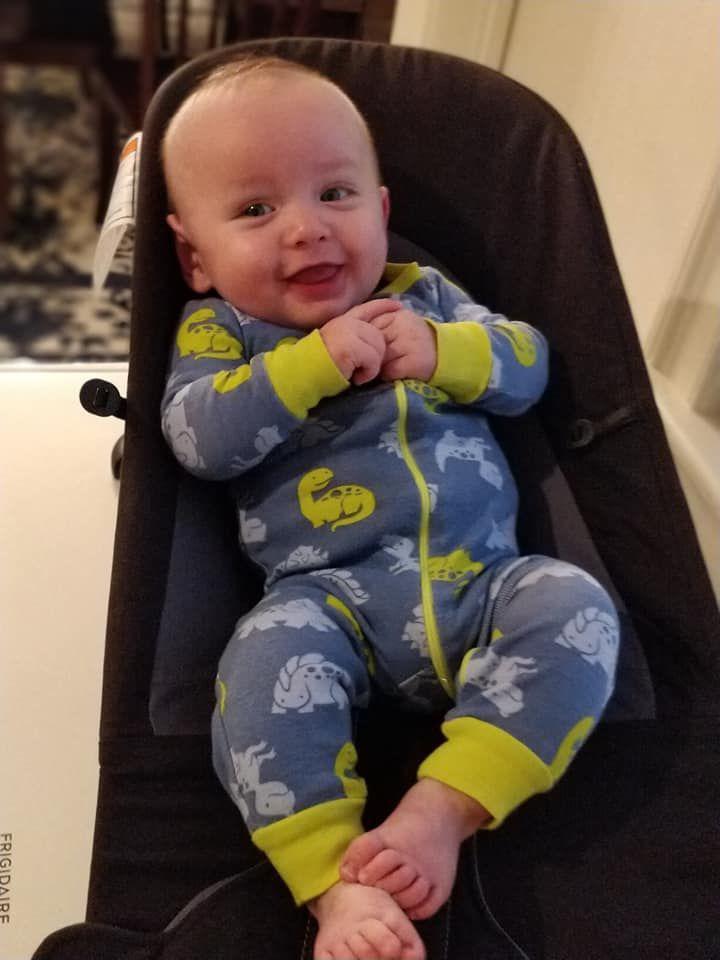

Once Hansing arrived at the hospital, doctors held her off from delivering the baby for a few days. Right at 24 weeks, she gave birth to her son, Charles Rex Hansing —”Charlie” for short — four months early in 2017.

Hansing would visit Charlie in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) daily for the three and a half months he spent there. But around these visits, she had a few hours a day where she would have loved to think about anything else, she says, which is why she tried to come back to school part time.

“The only thing I needed was a place to pump on campus,” she says. But finding and accessing the University’s handful of lactation spaces in a 2000-acre campus proved difficult.

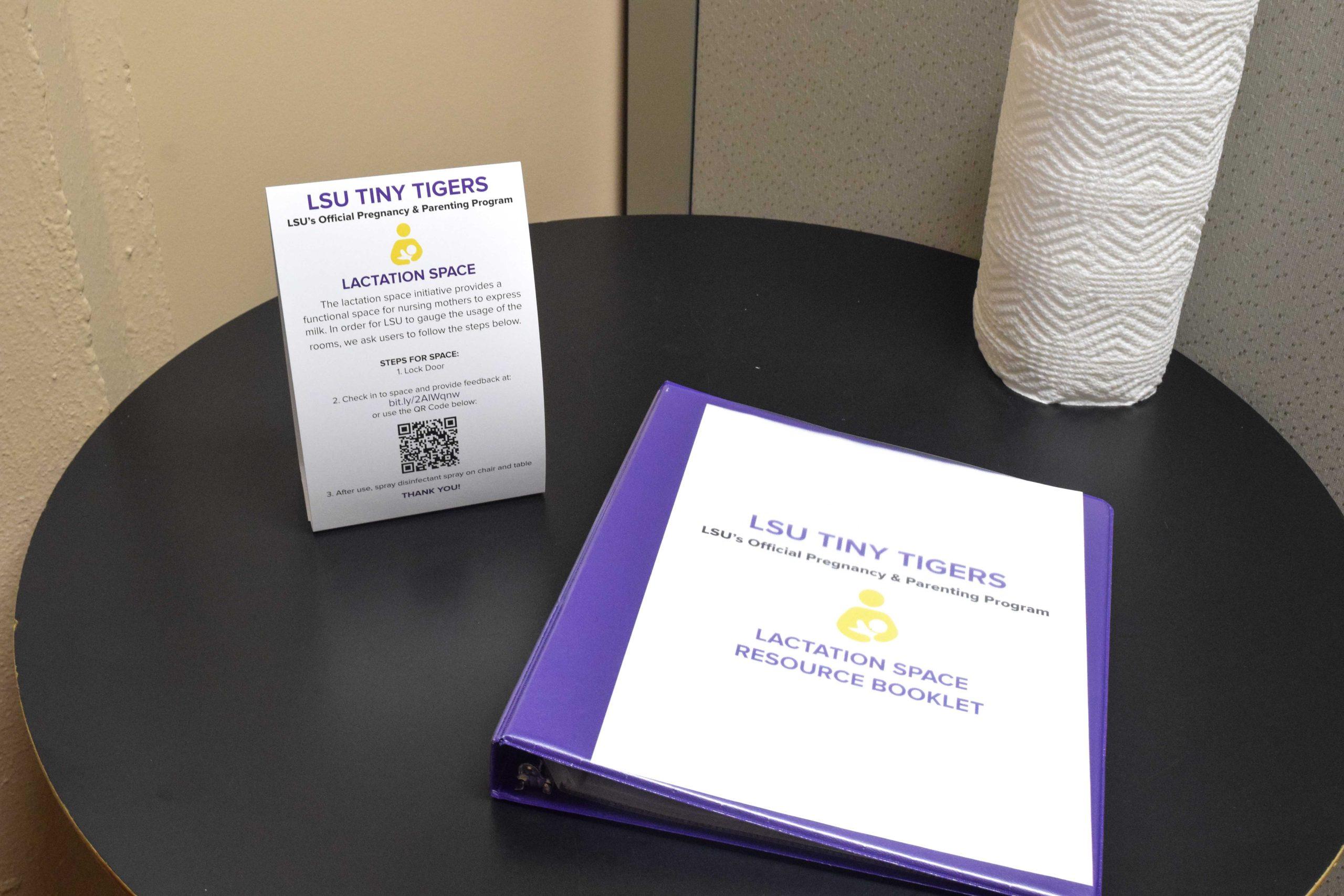

The University increased the number of lactation spaces on campus after the LSU Staff Senate introduced Resolution No. 17-01 in 2017. The push was a culmination of Hansing’s concerns, as well as other mothers on campus. After the Staff Senate introduced the legislation, several University departments came together to form the University’s first Lactation Room Committee.

On Nov. 6, the Lactation Room Committee helped launch the website for the University’s new pregnancy and parenting program, LSU Tiny Tigers, with resources for students, faculty and staff. The committee was comprised of representatives from Staff Senate, Faculty Senate, Academic Affairs, Human Resource Management and the Dean of Students.

The webpage, available through the LSU Women’s Center site, links campus mothers to resources like temporary medical parking and case management services, and provides a map of lactation rooms and their respective hours.

Facility Services assistant director Tammy Millican says apart from the at least 10 lactation rooms currently available for use, the University is working on securing seven others.

“The other ten rooms need a varying amount of work, so there is no firm date yet to have all of them available,” Millican says. “We are already working on the rooms, and the ones that need only minor work will be available soon.”

University administration provided funding for spaces that needed locks, outlets, chairs, or signage to be used as lactation rooms, Millican says.

Millican says the University is also working on a communication plan to publicize the new and existing lactation spaces on campus. The new parent resources page is part of that campaign.

“What we’re trying to do is make it consistent, so that if you come to campus, you know here are all the locations, and here’s what you need to do to use them,” Millican says.

Student parents make up 26 percent of the total undergraduate student body in the United States, according to a 2017 report by the Women’s Institute of Policy Research.

“We’re everywhere,” Hansing says. “We just haven’t forced the system to accept us as real people.”

Additionally, several majors require students to be on-campus after business hours for lab work, theater practice or other activities. But most of the University’s lactation rooms close around 3:30 p.m.

Currently, the LSU Tiny Tigers map lists two after-hours lactation spaces: one in Patrick Taylor Hall, open until 10 p.m., and the other in the Student Union, open until 11 p.m.

“What’s crazy is that this is not a new problem,” Hansing says. “First of all, women have been having babies for forever. Then, LSU has been around for a really long time, and the way they treat athletes or people going to the gym … I mean there’s a lazy river, but there’s [barely any] after-hours lactation spaces on campus.”

For Hansing, pumping breast milk for her son every few hours while he was in the NICU was a matter of life or death for him. She was under strict orders from her son’s doctor not to pump in any bathrooms because it was unsanitary.

Walking long distances in the summer to the nearest lactation space was also risky. Hansing constantly worried about staying hydrated and well-fed in order to produce enough milk for her son. “Every single decision in my day had a consequence,” she says.

Hansing recalls asking herself all the time, “If I go to school, if I miss a pump, if I miss a meal, if I get dehydrated, if I have to walk all the way from the Ag lot to my building, is it going to kill my son?”

“You just feel totally trapped, and all you want is to do right by the person you promised to take care of,” she says.

Soil science graduate student Crystal Vance-Rogers was going to school full-time and working as a teaching assistant when she found out she was pregnant. She continued taking classes and teaching until she was nine months pregnant and delivered her baby at 41 weeks.

But suffering from morning sickness made attending her early soil physics class a challenge. “I would literally be in class, and as soon as I got to class, I would run out the restroom because I would be so sick,” Vance-Rogers says.

Still, she did not want to tell her professor she was pregnant.

“I didn’t want to use my pregnancy as an excuse for people to feel sorry for me, so I kept going,” Vance-Rogers says. “I never would say, ‘Hey, I’m pregnant.’ I would just come to class sick and try to stick it out.”

Finding an affordable child care option in the area can also be challenging. Both Vance-Rogers’ parents and in-laws lived out of state, making finding a child care provider an immediate necessity. Hansing says her friend’s child was on a waiting list for four years.

Vance-Rogers says it took her about five months of researching before she found a suitable child care option for her son.

“When I finished doing work at school, I would sit in the computer lab and write down numbers and I’d call,” Vance-Rogers says. “Either they’re full or they’re going to put you on a waiting list. You have to keep calling every other day.”

Additionally, Vance-Rogers says the daycare in the areas surrounding the University were expensive. She had to be particularly conscientious of the location of the day care, since her and her husband share a car.

Vance-Rogers pulled her son out of the first child care center because she felt it was disorganized. But the transition of enrolling him into another center caused her to miss class frequently.

“Sometimes I brought him to class with me,”Vance-Rogers says. “It was okay in the early stages because he didn’t talk as much or make noise. But he started talking, and it’s like, ‘Okay, I can’t bring him anymore.’”

Hansing signed her son up for the LSU Early Childhood Education Laboratory Preschool, the University’s on-campus child care center, when she reached her second trimester—even before he had a name. She had heard stories from a friend whose child was on the waiting list for four years.

Hansing worries her son will not get into the on-campus child care before she graduates. Then, she will no longer have student priority on the waiting list, one of the highest priorities.

Hansing says that the lack of resources for mothers on campuses across the nation causes many women to drop out of STEM programs, especially since many advanced degrees take five to seven years to complete.

“Plenty women apply and get accepted into STEM programs, but there’s a huge percentage that drop off or end up working from home,” Hansing says. “I can tell you why: part of the reason absolutely is that there’s no support for moms.”

Vance-Rogers says that before she met Hansing and two other mothers in her classes this semester, she had never met another student mom. She says talking with other moms about their experiences can go a long way.

“It’s like you’re alone in this mom world, and it’s hard,” Vance-Rogers says. “You’re around the clock 24/7, and sometimes you just need that support group just to talk to somebody.”

“Because post-traumatic stress disorder is real,” she adds. “I don’t think people realize that, and I think some moms feel like if they just had someone to talk to about it, it would be okay.”