A law that took effect Aug. 1 is diverting state funds for indigent defendants facing the death penalty to district public defender offices to represent those charged with less sever offenses but who cannot afford a lawyer.

That is what the law was meant to do and it’s creating a crippling situation, warns the Louisiana Public Defenders Board (LPBD) headquartered in Baton Rouge.

Currently, there is a wait list of a dozen defendants charged with capital crimes waiting for a lawyer to be appointed for their cases, says Jean Faria, the Capital Case Coordinator on the defenders board.

While the wait list has been sporadically necessary since 2014, the most recent cuts have exacerbated delays by eroding the capacity of organizations to handle capital cases, according to Faria.

For lawyers defending capital clients, the wait period can be damaging to building a defense. The greatest fear, they say, is evidence disappearing or the erosion of its usefulness at trial.

“Let’s say there is a video in a gas station that exonerates your client—that’s not going to be there very long,” said Louisiana State Public Defender Jay Dixon. “You have to jump on this stuff. From where I’m sitting, as a former capital defense lawyer, a day [on the waiting list] is bothersome.”

Records that provide information about the history and mental state of the defendant, which could potentially preclude the death penalty, are time- sensitive, he added, underscoring that schools and other institutions destroy records when they no longer find them relevant

Investigating a case immediately can potentially reduce a first-degree murder to a lesser charge in which the defendant would not face a death penalty.

“You can’t do anything with a capital case until you investigate,” said Faria.

The law, sponsored by Rep. Sherman Mack, R- Albany, mandates the Public Defender Board distribute 65 percent of its $33 million annual appropriation to the 42 district public defender offices.

Repeated attempts to reach Mack for comment went unanswered.

District offices also receive local funding from the parishes that make up each district. That funding comes primarily from traffic tickets and court fees, and tends to fluctuate with many of those operations struggling to make ends meet.

Dixon says that 14 of the 42 public defenders offices in Louisiana are limiting services due to lack of funds, and offices in New Orleans and Lafayette have their own lists of indigent defendants awaiting legal representation.

Previously, many districts have taken on their own capital cases, but due to funding losses almost all have now handed over responsibility to the state.

Currently, the defense of capital cases primarily is handled by non-profit law firms under state contracts. These include Regional Capital Conflict Panels which handle cases at the district level, the Capital Appeals Project which argues appeals to the Louisiana Supreme Court, and the Capital Post-Conviction Project of Louisiana (CPCPL) which represents condemned inmates currently on death row.

Gary Clements, director of the post-conviction project, headquartered in New Orleans, said he was forced to cut his staff in half. And while he attempts to make due with limited resources, the nature of the work is not conducive to cutting corners.

“When somebody’s life is on the line– and all of our clients have their lives on the line– it’s not something we can do at a bargain- basement situation.”

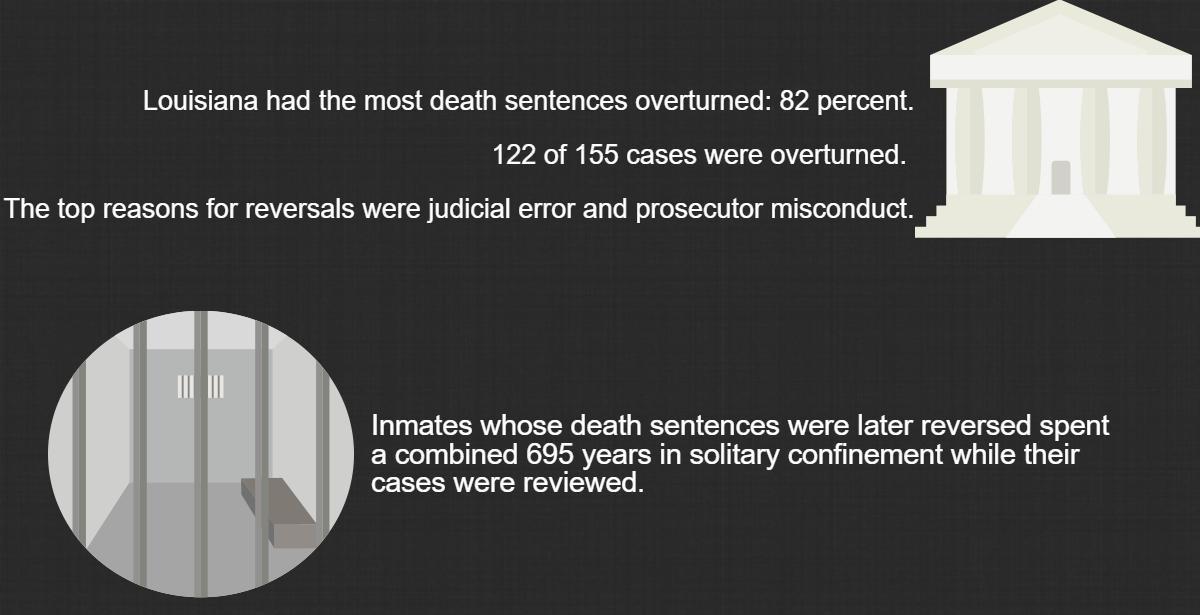

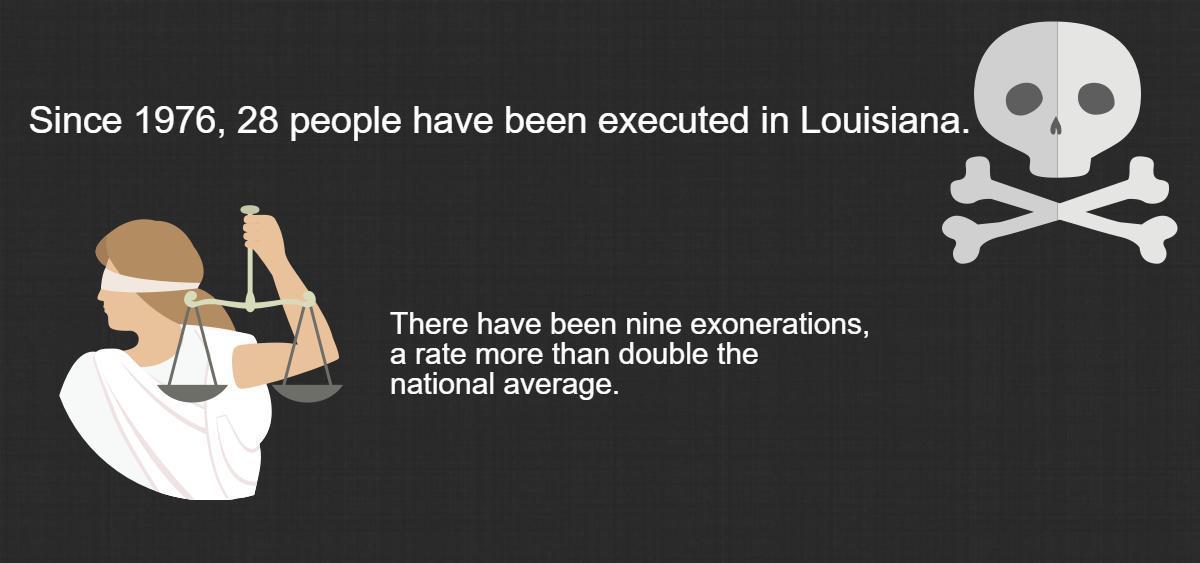

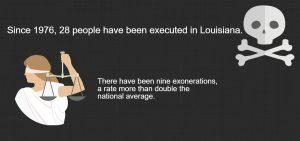

A 2015 study published in the Southern University Law Center’s Journal of Race, Gender, and Poverty reviewed every death sentence in Louisiana which highlighted a legal process fraught with error: 82 percent of all resolved death penalty sentences since 1976 have been reversed, with nine exonerations. The primary reasons: judicial error and misconduct by prosecutors.

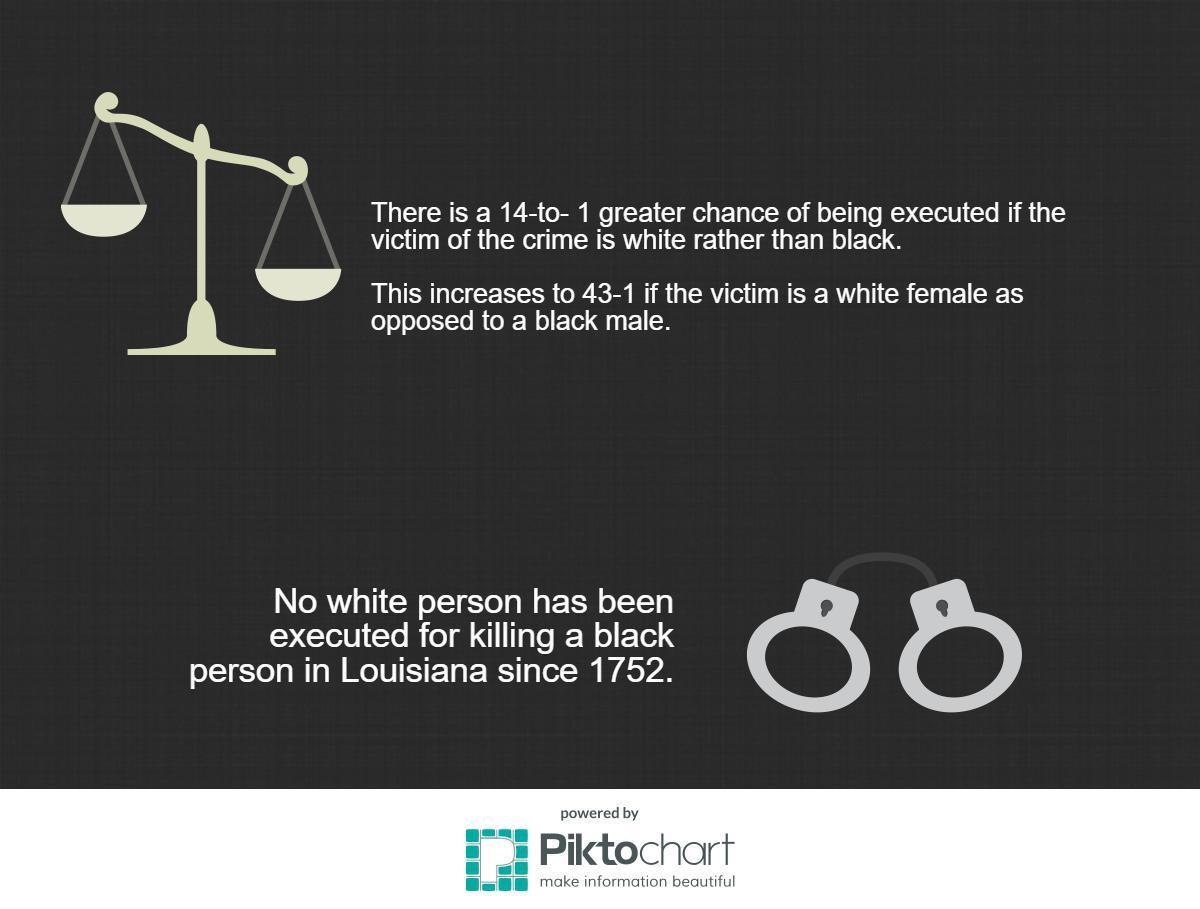

The study also finds a disturbing racial bias in how the death penalty in Louisiana is administered. For instance, no white person has been executed for killing a black since 1752 — a fact the study calls “perhaps the single most shocking element of Louisiana’s experience with the death penalty.”

In March, Michael Wearry, a Louisiana man sentenced to death in 2002, was given a new trial by the U.S. Supreme Court which found that the prosecution had withheld exculpatory evidence, facts that could have helped his case.

In its decision, the Court said that the state’s trial evidence “resembled a house of cards.

Faria says the lack of a uniform system of public-defender funding throughout the state has prompted some defenders believe their obligation is to their immediate clients only. While that can be an appropriate response, she says, there needs to be a push by leadership at the Louisiana Legislature for more funding across the board.

“This is not about power,” said Faria. “This is about poor people accused of a crime. This is not about silos. This is not about protecting turf.”

“We’ve done all the rearranging of the deck chairs on the Titanic that we can do. This is about lack of funding for an entire system.”

Death penalty public defender wait list growing with delays

November 25, 2016

More to Discover