We at LSU recently lost our beloved mascot, Mike VI. He was peacefully euthanized as a way of ending his suffering when it became obvious that the quality of his life was unlikely to improve.

People accepted this conclusion to his short life. It is a story we all know extremely well and are comfortable with hearing — regardless of how it makes us feel.

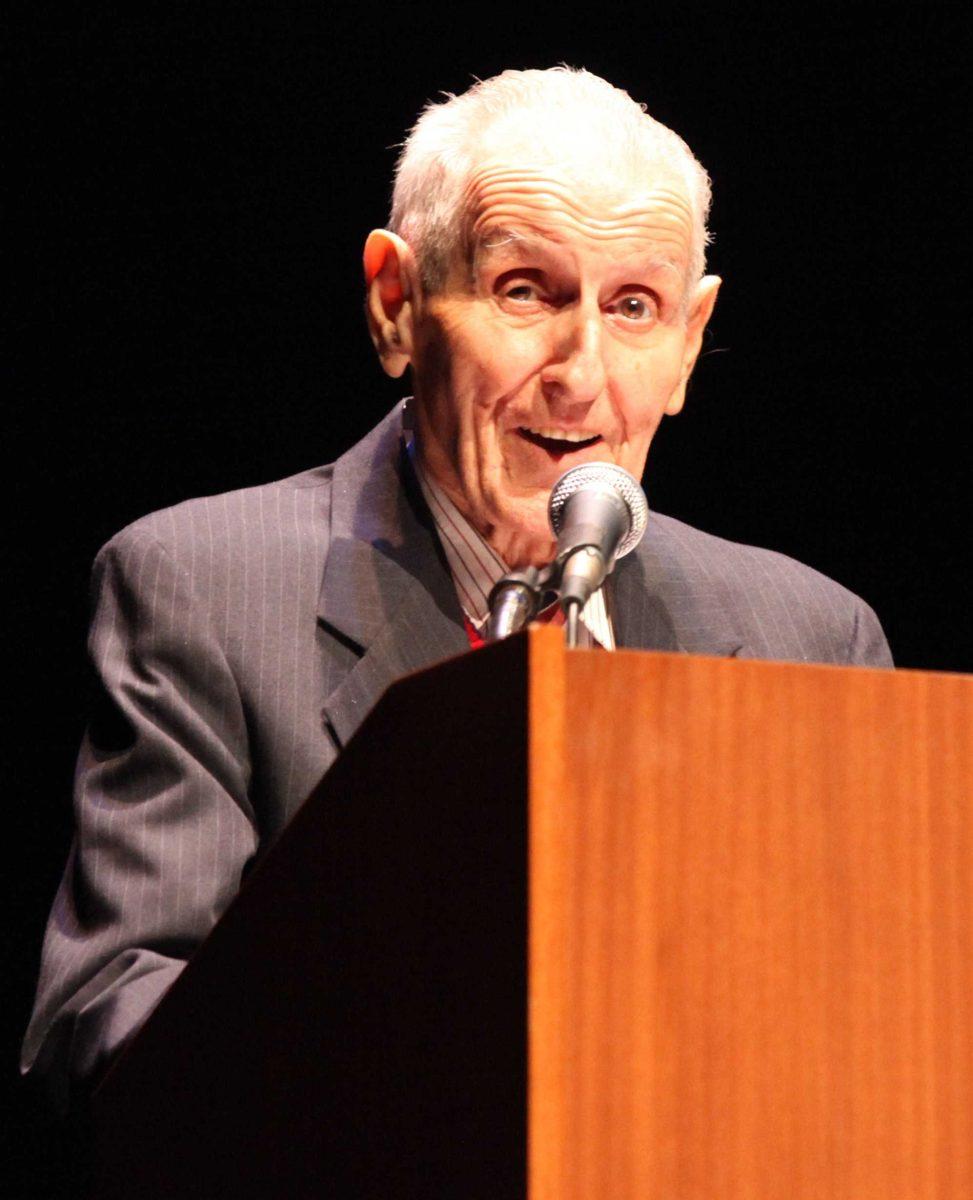

When a poor and helpless animal is suffering, we know euthanasia is a possible answer to ending the pain of our beloved quadrupedal friends and family whom we wish not to see tormented by illness. And, as Jack Kevorkian said, “How can you regret helping a suffering patient?”

Yet, for some reason, the same principle seems to become hard for many people to swallow whenever it is applied to human beings, themselves. To those who are suffering, the widespread distaste for human euthanasia is a devastatingly great injustice.

The masses so often cast dissent toward the idea of human euthanasia, simply because they can’t relate to wanting to die and refuse to imagine a situation so horrid in which their only wish would be to do so.

Strangely though, they can imagine things of equal outcome.

For instance, many people are under the impression that capital punishment is a just method to deal with criminals.

It seems that people in this society are entirely willing to take a perfectly healthy human — who desires with every shred of his or her being to be spared death — and kill them for the sake of revenge. Yet the same people can’t bring themselves to approve of a person in dire circumstance and endless pain who is content with the idea of death and in fact embraces it and begs for its arrival — being allowed to bring about their own end in the manner of their choosing.

This is a sad problem with human nature. The feeling of revenge is simply more relatable than the feeling of helplessness. People don’t want to think about death.

Albert Camus, a French-Algerian philosopher, once made the valid point that, “We get into the habit of living before we acquire the habit of thinking.” It is for that very reason we are far more comfortable with living than we are with thinking about or questioning the matter. It is also for that reason that we wish to avoid thinking about how our lives shall end — whether it be by choice, time or accident.

It is far more comforting for most people to think about the feelings of life, such as revenge. This is why we allow an execution before we would allow a suicide. This is why more people are willing to fight for the rights of the life of something in the embryonic stages of prenatal development than they are for the rights of the tormented to die.

The living, naturally, always fight for life and the feelings associated with it. Though they might fight over deaths, they have never truly fought for it. If they have, it has usually been out of revenge for a death worth fighting over.

Ultimately, however, the feelings of the masses seep into every crack in the busted sidewalk of our society. Now, it is nearly impossible for someone who is suffering and living life with a quality so low that they have decided that the relief of passing would be better for them and their loved ones to get the procedures that they need to finally be at peace.

That is why I say again, this widespread distaste for the practice of euthanasia is a great injustice. It forces those whose lives are nothing but pain to live. It is undeniably a passive form of torture. It causes the suffering to be forced to live with their pain the rest of their days or to go to apprehensive medical practitioners for assistance.

The most famous of these doctors was Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a pathologist from the University of Michigan. He performed several procedures of euthanasia, which were given the harsher name “assisted suicides.”

He was seen by some to be a hero, and by many to be a murderer unfit to call himself a doctor. Yet, just as we don’t call a veterinarian who euthanizes a dog a poacher or a hunter, it is a great falsity to claim that a medical practitioner who condones human euthanasia is a murderer.

It is all part of this stigma surrounding death. People don’t know enough about the matter to approach it. They believe an executioner is righteous and that a doctor who euthanizes someone is a demon of some breed.

Kevorkian said himself, “There’s no doubt I expect to die in prison,” due to to the charges being placed on him for conducting his procedures. That, I say, is not an expectation that someone who wishes to help the suffering should ever have.

This world, and these creatures that we are, are the things that limit us just as much as they empower us. We reason only in ways that are comfortable and easily understandable. We pass judgments as though we are all knowing.

When those judgments bring about the suffering of others, know that you are not as innocent as you think you are.

The suffering should have the right to their life — the same right every human should have.

Our life is the first thing we ever own, and the last thing we ever will. It is every human’s right to decide what becomes of their lives and how it concludes. It is the last thing we have in the universe.

For those who have nothing else but a life of pain, it is their right to find the peace which they desire and their right alone.

Jordan Marcell is a 19-year-old studio photography and linguistic anthropology sophomore from Geismar, Louisiana.

Opinion: Allowing for euthanasia reduces suffering

October 19, 2016

Dr. Jack Kevorkian speaks at “An Evening with Dr. Jack Kevorkian,” hosted by the UCLA Armenian Students’ Association and the Armenian American Medical Society of California. UCLA Royce Hall Auditorium