In academia, the work one does often feels solitary and requires little collaboration with others, especially when it comes to ethnographic research, but Southern Illinois University professors Craig Gingrich-Philbrook and Shelby Swafford challenged this in a lecture they gave last week at LSU.

On Nov. 19, the LSU Department of Communication Studies held its third annual Place of Performance lecture at the HopKins Black Box Theatre, a series highlighting distinguished scholars and artists who have used performance in public lectures about their work.

This year’s lecture, held by Gingrich-Philbrook and Swafford, was titled “Hydrangeas and Lilacs: Intergenerational Collaboration and Mentorship in Autoethnographic Performance Studies.”

Performance studies is a field originating from communication studies and the social sciences that examines performance, what it communicates and how it applies to culture, society and the world. Autoethnography requires the researcher to use ethnographic techniques such as interviews and observations to study their own lives and experiences.

In this lecture, Swafford and Gingrich-Philbrook integrated their background in performance studies with autoethnography.

People lined the walls before the event, waiting for the Black Box to open. Many knew or had heard of Gingrich-Philbrook and were excited to hear him and Swafford talk about their work. A student even brought their performance studies textbook that Gingrich-Philbrook co-authored for the two professors to sign.

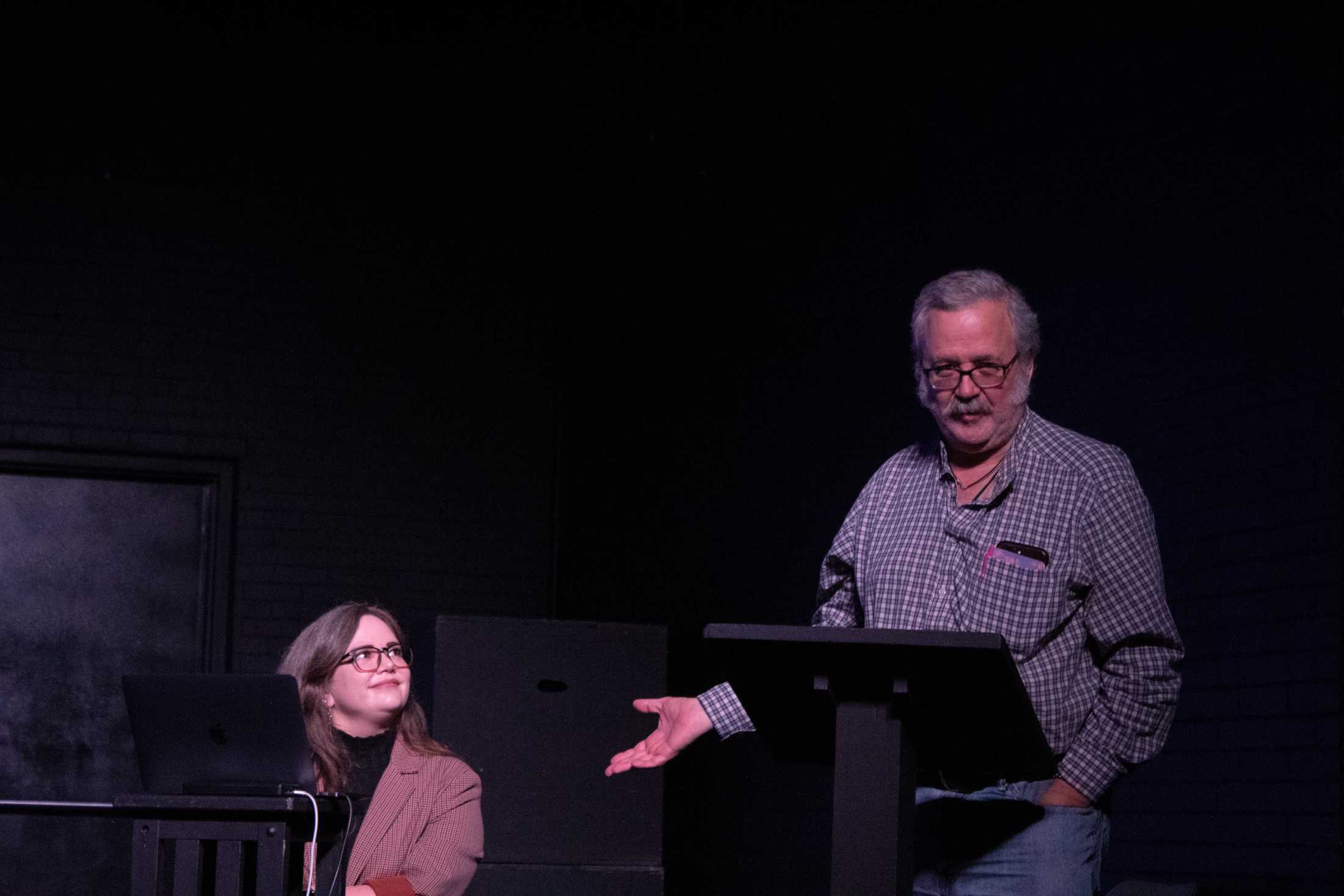

The lecture started with some words from LSU’s Communication Studies Department Chair Tracy Stephenson Shaffer. When introducing Gingrich-Philbrook, she said, “I really cannot think of a practitioner that has made a bigger impact on communication studies, performance studies, through his written and staged research, mentorship of others and his service to the performance studies division of the National Communications Association.”

Swafford rose and told the audience how she and Gingrich-Philbrook began to work together. She had taken his classes for years, but Swafford said, “I hadn’t felt that I truly knew his work until the early days of the COVID pandemic.”

As the world fell into disarray, she went through SIU’s theatre archives, using the recorded performances to dissociate and cope with the challenges of the pandemic. Looking through these archives is how she really connected with Gingrich-Philbrook, who was a key figure in many of the archived performances.

Swafford went from watching performances to writing about them for her dissertation. From here, she began performing parts of these productions with Gingrich-Philbrook.

“That seat of sensation in which we experience, receive and interpret the world around us, reclaiming our agency through the interpretive process and trusting our senses as we made sense through art,” Swafford said. “It’s the kind of thing one learns from audiencing Craig’s work. So we help each other see the hydrangeas and smell the lilacs; we are just midwives for each other. We participate in performance as an act of caregiving.”

Swafford finished, and Gingrich-Philbrook took the floor to speak. Throughout the lecture, Gingrich-Philbrook made occasional repetitive, involuntary movements with his head. As he began to talk and these movements happened, he told the audience he’d explain them later.

He continued by telling a story from when he went to school in the ‘70s. Gingrich-Philbrook was presumed to be queer and was sent home with a note one day saying he was being “socialized incorrectly.”

“I, in seventh grade, lived in a little mountain town where the junior high and the high school were one, and a bunch of the older boys pinned me against a wall and took turns stomping up and down on my feet for, I don’t know how long,” Gingrich-Philbrook said, “wanting me to admit I was queer. It was a few months after that my father died … then I began small movements.”

Gingrich-Philbrook referenced a Human Rights Campaign study that said around 46% of LGBTQ+ students and almost 55% of transgender students feel unsafe in school settings. He also referenced a study that stated these students are three times more likely to experience anxiety, depression and neurodevelopmental disorders, with transgender people being six times more likely to consider suicide.

“The so-called ‘normal folks’ don’t have to explain,” Gingrich-Philbrook said, “but there are some people who learn the habit of explaining their bodies, the presence of their bodies, how they use their bodies. LGBTQIA+ kids are asked to explain their existence and experience and bodies all the time … Bodies that are politicized in ways that have long-lasting effects on their minds and their central nervous systems.”

Years after the note incident, Gingrich-Philbrook constantly surveilled himself, recounting all of his actions. He was diagnosed with functional neurological disorder, a condition where there is miscommunication between the nervous system, brain and the body. Gingrich-Philbrook’s movements would change in frequency and severity, increasing with stress and trauma.

“You could see how those things would be disrupted by a life of assault or trying to style your body in such a way that it would be acceptable to those around you,” Gingrich-Philbrook said.

Gingrich-Philbrook discussed the concept that scholars like him use their bodies as research to understand the structure of the wider world. He said that his work is to shine a light on the effects of “a lot of the rhetoric descending upon LGBTQIA kids today, particularly trans kids.”

The audience was talked through what was a 45-minute scene. Gingrich-Philbrook retold essential moments from his childhood and young adult life – experiences that stayed with him for his whole life.

Right before Gingrich-Philbrook played a video of one of his performances, he explained what the lecture title references: lilacs and hydrangeas sitting in the background of the video.

“Lilacs that represent the reclamation of my childhood,” he said. “The first time I kissed a boy was under the lilac bush.”

In the video, Gingrich-Philbrook tells the story of reconnecting with long-lost family members through a reality TV show. Right as the video gets to the moment when he meets these family members, it stops. As others tried to fix the video, Gingrich-Philbrook began to talk to the audience. He explained a recurring nightmare of his father showing up at the door, Gingrich-Philbrook hugging him and his father dying once more.

The audience was captivated as Gingrich-Philbrook told the story of this replaying in real life. He was going to meet his nephew for the first time, open the door and embrace the last piece of his father.

Gingrich-Philbrook continued his story and fell into performing the rest of the scene for the audience. He told the audience about a thread he found in his experiences. The thread, he said, he pulled and pulled to unravel a tapestry of anchoring truth. The room was left in crushing silence as Gingrich-Philbrook finished until the audience roared with applause.

As the lecture ended, Gingrich-Philbrook reiterated the importance of young mentors and the reciprocal relationship he has with Swafford. Since they began working together, he felt them “co-regulating” or practicing “interpersonal synchronizing,” the moment when people’s minds and bodies match and behave together.

Swafford said one of the biggest things she has gained and will continue to take away from working with Gingrich-Philbrook is “not being afraid to ask to learn together.” Gingrich-Philbrook added that collaboration and learning felt mutual throughout all their work together, referencing how Swafford has taught him through their collaboration. Swafford explained she hoped audience members would take away the importance of cooperation from the lecture.

“To lean on each other and form collaborative relationships that will carry you through beyond just one project that becomes an enduring relationship.”

Gingrich-Philbrook said he is still trying treatments for his FND. “One of the things I have to do is to use it as evidence that hate persists,” he said. “And that persistence in the nervous systems of young people who one day grow old is precisely by design. And that grown-ups that spread lies about LGBTQIA+, particularly trans kids, have a special kind of problem.”

He continued to talk about how systems and the social world affect kids and how it lasts, emphasizing the healing performance can bring to these children.

“I hope [these kids] find performance, and kinship, and friends, and a way to use their bodies to do what they have to do, which is to tell a story of our experience that helps us make sense of it.”