How would America’s voter turnout change if they thought heaven depended on it? Or how would the legacy of the Occupy Movement be different if participants were greeted with bullets instead of broadcasters?

In numerous countries today — most notably Syria and Egypt — millions of people struggle with the implications of questions like these. Native Egyptians, whether in Tahrir Square or the University’s Parade Ground, have seen their country, family and friends suffer in the latest standoffs between the military-led interim government and the typically maligned Muslim Brotherhood since former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi was ousted July 3.

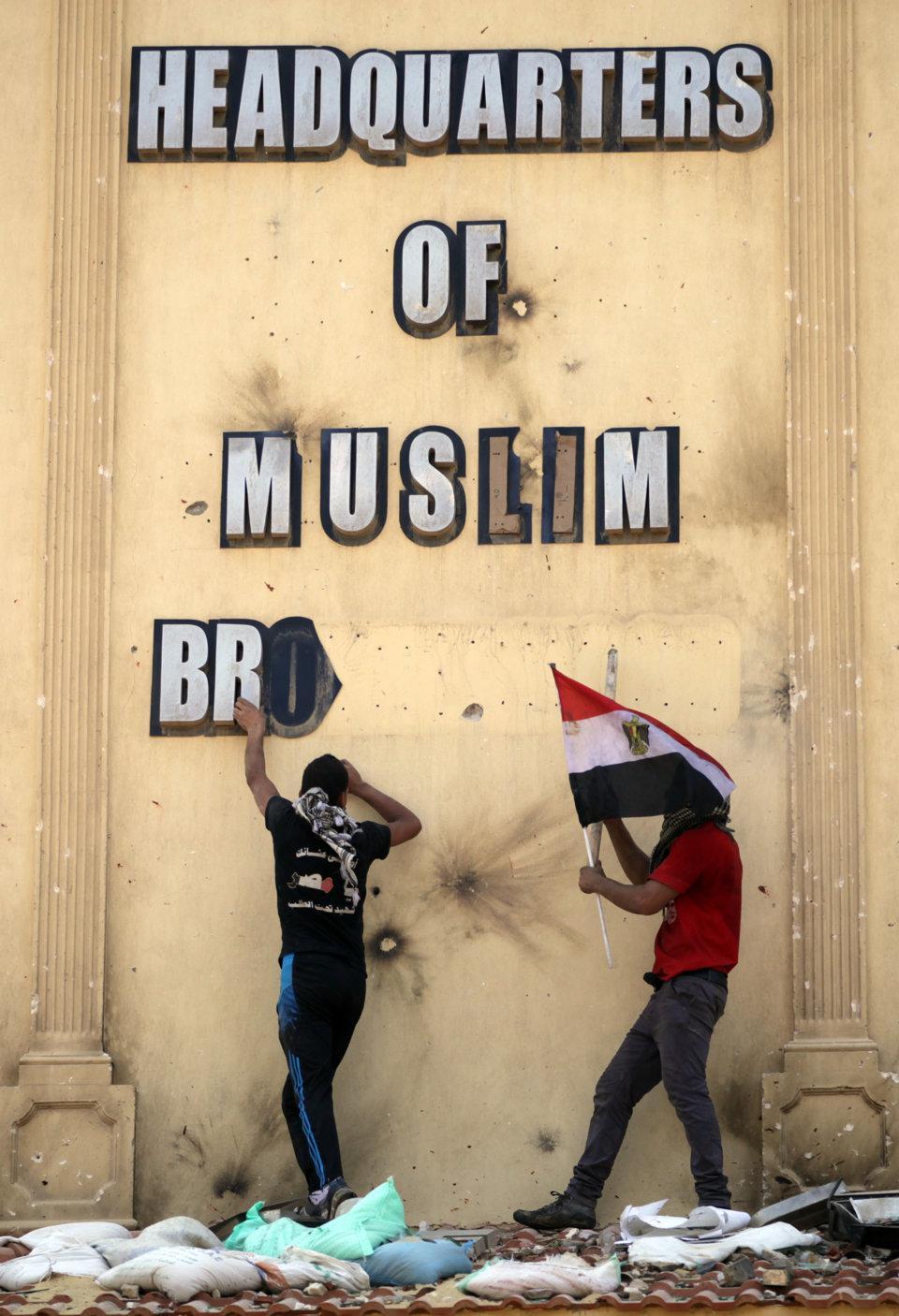

Try though they may, presenting an unbiased depiction of the Muslim Brotherhood’s place in Egyptian society is almost impossible. Even after a month of violent crackdowns and extensive arrests, an Egyptian court mandated the Brotherhood be completely disbanded Monday, as well as the new, Brotherhood-backed constitution be entirely rewritten.

Diagnosing a Coup

Started in the 1920s as an opposing force to British colonialism, the Brotherhood is an Islamist organization that has represented the most organized opposition to dictatorship in Egypt since the group’s inception, though it was banned from politics until Egypt’s former dictator Hosni Mubarak fell in 2011.

Ahmed Mansour, an LSU Ph.D. student who attended protests against Mubarak as well as against Egypt’s current interim government could hardly contain his emotions as he discussed the most recent violence against the Brotherhood.

“If the nation’s request is to kill a person, do you just go and do it? It’s still a crime!” Mansour said, remembering the friend he lost in one of the latest crackdowns. “This guy didn’t even belong to the Muslim Brotherhood; he was there because he is against cruelty.”

Mansour was born in Egypt and moved to the United States in 2001, but he has frequently returned home to Cairo, most recently this August.

Despite the typical us-versus-them portrayal of the Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt’s military council, support and opposition to the Brotherhood vary monumentally. Like his deceased friend, Mansour does not call himself a member, though he has participated in the group’s sit-ins and laments the recent removal of Morsi, the Brotherhood’s candidate in Egypt’s first democratic election in decades.

While Mansour decries what he calls a coup against a democratically elected president, others find themselves struggling to maintain a moderate viewpoint of Morsi’s ouster and the military takeover, made all the more difficult after the imposing military killed hundreds — allegedly thousands — of Brotherhood protesters.

“I hate stereotyping because there are so many circumstances that happened and it was very special. I cannot call it a coup, and at the same time, I cannot not call it a coup,” said Ahmed Hegab, a University master’s student who also grew up in Cairo, leaving in 2010 to get his degree. “The coup was supported by 20 million people — it didn’t happen until people really demonstrated that they wanted change. But Morsi refused.”

Both Mansour and Hegab agreed the adherents of a group cannot be defined by their leaders, and as Hegab describes it, the Egyptian people had to decide between old and new in the voting booth.

“They basically were choosing from the best of the worst,” Hegab said.

And despite the media’s black-and-white portrayal of the Brotherhood, Hegab pointed out that the leaders cause the problems, not the supporters.

“Some people, they had so much passion and sympathy for [the Muslim Brotherhood] because they had so many slogans from the Islamic ideologies and principles, but it was proven by time they were wrong — they were just slogans, they were just trying to get people on their side,” Hegab said, adding that this bait-and-switch has been utilized by many politicians who used the Brotherhood’s, and Islam’s, creeds to win political support. “The religion card was used by politicians very recently to play games — divide and conquer. But the Egyptian people are moderate.”

A Place for Religion

Herein lies the predicament in which countless moderate Egyptians find themselves: Voicing support for or against the Muslim Brotherhood inevitably entangles religion, and after the intense violence that befell them, many who oppose the Brotherhood struggle to find the line between condemning and condoning the crackdown.

“The majority of Egypt, in my opinion, thinks Islam is a very good religion — in the mosque. If you insist on taking your religion outside of the mosque, then you are a fascist,” said one student, who, because of the tensions that have arisen for him when voicing opposition to the Brotherhood, chose to go by the pseudonym Sayed. “Religion is something very good in the mosque, in your morals. The Muslim Brotherhood take it to the next level, and they insist on taking religion outside of the mosque.”

The coup, he said — and he does call it a coup — was not a public revolution, and the military that conducted it does not possess a vision or dream for Egypt. “Even assuming these bad things, I have no choice. Who to choose from: theocracy, or military dictatorship?”

“At least in a military dictatorship, you have no choice in politics. But nothing else. I can have a girlfriend, go to bars. … In theocracy, it’s not only public rights, or political rights, it’s personal rights, and they will interfere with your way of life. I would choose military dictatorship over theocracy.”

Still, Sayed and Hegab speak of the leaders, not the regular members of the Brotherhood who, as Hegab put it, tend to be just as well-spoken and moderate as the rest of Egypt.

A New Era

Though Mansour sees the brighter side of the Muslim Brotherhood’s recent popularity in Egypt — namely, the outpouring of sympathy for their loss at the hands of the military — Hegab and Sayed seem to agree the Brotherhood’s political future is over.

“People who are supporting them are against what is happening to them right now — because they are human beings, not to have them come back to power,” Hegab said. “If presidential elections were to come, I don’t think by any means one of the Brotherhood’s candidates, if there is one, would win.”

Sayed said he sees the latest coup as a transition, and hopefully one toward a more moderate, educated and relatively secular Egypt.

“What people are happy about right now is that it’s the end of the era, the end of imperialist, fundamentalist ideologies,” he said. “Christians, Muslim liberals and moderate Muslims in Egypt are very happy about it.”

For the foreseeable future, it is unlikely religion will cease to both define and distort the political struggle in Egypt, but Mansour, Hegab and Sayed each testify to Egypt’s predominately moderate population.

“I think people are worried the religion card would be pulled and cause more tensions [because] it’s part of the Egyptian identity to be moderate,” Hegab said.

The End of an Era: University Egyptian students reflect on dismantling of Muslim Brotherhood

September 23, 2013

Muslim Brotherhood