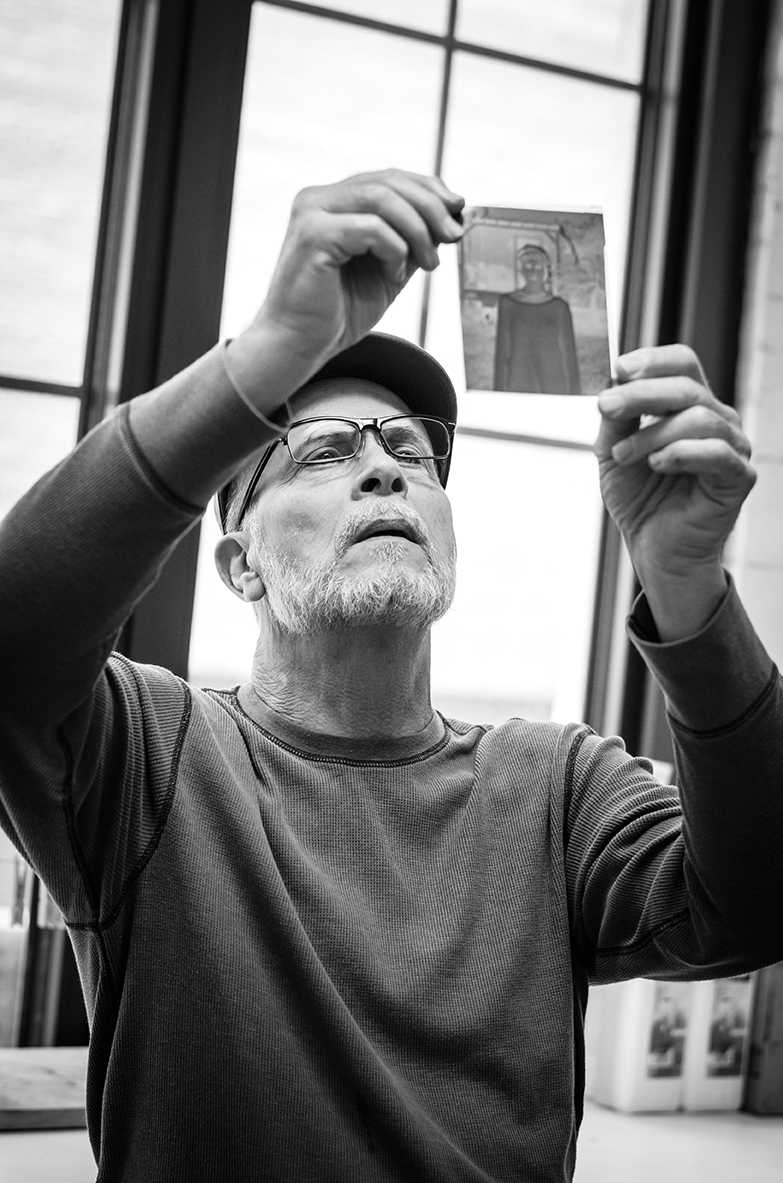

Students always knew photography Professor Thomas Neff had high expectations. The 65-year-old artist’s dedication to technique and traditional black and white photography, combined with uncompromising honesty, make Neff’s classes challenging, but transformative.

However, a stroke in October 2013 left Neff temporarily paralyzed and mute. His only way to communicate was gently squeezing with his left hand. Family, friends, students and coworkers feared he might never recover.

But Neff always had high expectations.

From his recovery, to his craft and classroom, Neff is defined by his persistence.

Neff is quick to say he loves his students.

“Always have, always will,” he said, smiling. “They are my joy.”

But in his 32 years at LSU, Neff’s relationships with his students have been shaped by his resolute demand for excellence, a demand that tests and transforms.

Photography seniors Brittini Bell and Katie Crawford first met Neff as sophomores in his intermediate photography class. Both students described Neff as a film-extraordinaire and master technician.

“I was a little intimidated,” Bell said. “Everyone talks about how serious he is about it [technique].”

But learning techniques like the zone system, a method of capturing the range between true black and white in film photography, helped convert a subjective art form into a procedural operation. Bell and Crawford described how Neff requires students to keep extremely detailed technical notebooks, which he uses to correct composition, exposure or even concept.

“He was very hands-on,” Crawford said. “If we were a minute off he would let us know and help us redo it.”

Neff explained that learning and executing proper technique is the fundamental principle of good photography.

“You have to make your photography as convincing as possible. Technique is only a way to say it better,” Neff said. “You have to convince the viewer that you put your heart into it.”

Neff also emphasized composure behind the camera, reminding students that they decide what a picture looks like – no one else.

“A photo is not the photography of one thing,” Neff said. “It is also a the relationship with the surroundings, deciding what to leave in and what to leave out.”

And Neff isn’t afraid to be brutally honest, saying it benefits no one to let mistakes slip by.

In fact, Neff’s honesty helped Crawford and Bell realize intermediate photography wouldn’t be like their previous classes. While graduate students who taught lower-level classes were quick to encourage personal growth and learning, Neff called out bad work.

Crawford described how Neff told a student her work was not was not good enough for the photography program in a final critique.

“He made a point to say, ‘You didn’t come and see me the entire semester. I could have helped you.’”

Helping struggling students find their photography style is what Neff finds most rewarding, he said. Ultimately, he believes students can find their true nature through the lens.

“My outlook of life is integral to my photography,” he said. “I only photograph what I feel passionately about. Over time, students can find that, too.”

Neff’s discovery of his true nature came when a friend in the Army Reserves introduced him to his first camera.

“I was curious about what he was doing,” Neff said. “Then I took a look in the camera lens.”

Curiosity turned into a passion, leading Neff to enroll in Riverside City College in 1969 and later to University of California at Riverside, where he completed his bachelor’s degree in fine arts. As a student, he met Herb Quick, an industry-renowned photographer famous for his command of light.

“I didn’t know his work,” Neff said. “I just heard he might offer a job. So I pestered him to hire me every week for eight weeks. I was determined to work with him.”

For five years, Neff worked under Quick as an apprentice, learning the zone system. Quick also taught Neff how to use a view camera, a machine the size of a bowling ball developed in the 1850s, which Neff continues to use today. However, Quick’s most valuable lesson was his unwavering work ethic.

“The way Herb pursued his work, he was a great technician and master printer,” Neff said. “I could say it shaped my life.”

Neff also studied briefly under Ansel Adams and Paul Caponigro during a weeklong workshop, which inspired Neff to pursue large-format and landscape photography. Neff’s interest in large-format photography stemmed from his obsession with detail.

“The large negatives provide an element of control. The process drew me in,” he said.

Throughout his training, Neff’s persistence to mastering detail and technique gave him an uncanny familiarity with his large, highly technical 5×7 view camera. He lugged his camera across the country as technique transformed into instinct, capturing diverse landscapes, architecture and people along the way.

After completing his master’s at the University of Colorado at Boulder, Neff struggled for two years before finding a job at LSU in 1982. He decided if he didn’t live in Colorado, then he wanted to live in another place entirely.

“Louisiana is the drippy South – both in the summer and the winter,” he said, laughing.

In Louisiana, Neff’s environment changed, but his devotion for capturing his subjects’ stories remained.

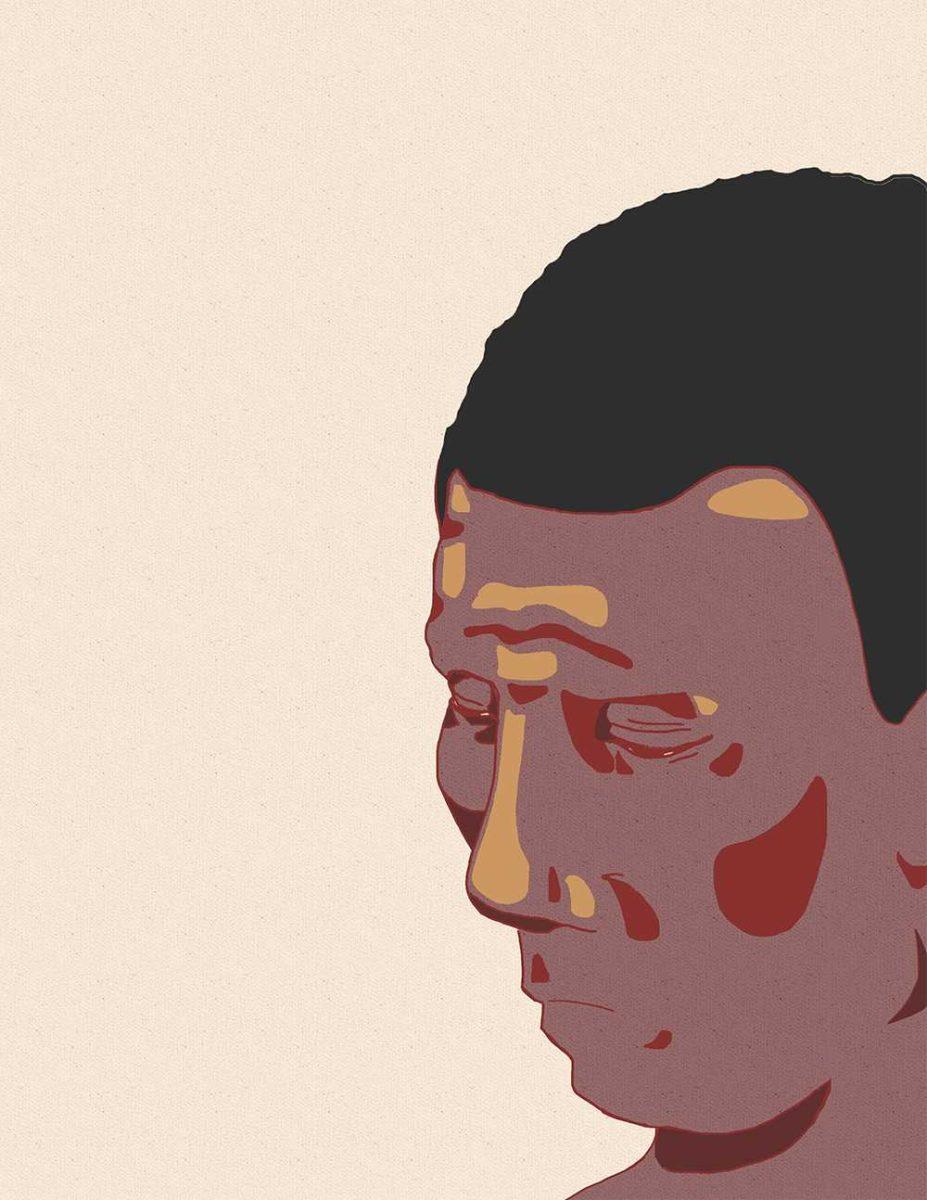

Assistant Professor Kristine Thompson, who has worked with Neff since 2012, said Neff’s work exemplifies his interest in getting to know his subjects, especially in his series following survivors of Hurricane Katrina.

In the months after the storm, Neff traveled around New Orleans, capturing the images of survivors and their environment. He spent hours speaking to each subject.

“He’s very interested in getting to know people, very easy to talk to,” Thompson said.

But a post-surgery stroke on October 16, 2013, left Neff speechless. Damaged receptors on the left side of his brain struggled to connect simple physical messages like swallowing. Doctors predicted Neff might never regain use of his hands or be able to speak again.

Emotionally, Neff also faced significant challenges. Although paralyzed, Neff was cognitive, meaning he was trapped inside of a body that couldn’t obey him.

But Neff was determined to break through. Beginning by squeezing his left hand, Neff astounded doctors and nurses by standing up just weeks after the stroke – even when he wasn’t supposed to, according to his wife, Sharon.

“He was very dedicated to showing he was going to get better,” Sharon said.

Neff’s tenaciousness made him an excellent candidate for rehab, where he focused on intensive physical, occupational and speech therapies. But as Neff’s recovery progressed, he became aware of his absence from the classroom. He worried about how his students, especially seniors completing their final projects, were progressing without him.

Meanwhile, his students worried about Neff. Bell and Crawford explained how upset they were to learn of his stroke, and they both wanted to find a way to show how much they cared.

“He means too much to us,” Bell said. “A card wasn’t enough.”

Students in the department worked together to make a quilt, decorated with drawings and signatures from dozens of Neff’s students. Neff beamed as he showed off the blue and white blanket. It was a surprise he said he’d never forget.

But Neff had a surprise of his own.

While it is customary for photography professors to visit the final art shows of graduating seniors, no one expected Neff to attend – no one, except Neff, himself.

When Neff walked into graduating senior Desiree Watkins’ final show, students were shocked, Thompson said.

“It was obviously important to Tom for [the students] to see how important they were to him,” Thompson said. “He was breaking all the rules, displaying the feistiness of his personality. That desire to be the old Tom was very present.”

Still on sick leave, Neff doesn’t work officially for the University. Instead, he unofficially assists undergraduates and graduate students by offering advice and critiques, and helps maintain the darkroom. He plans on returning to campus in fall 2014.

In the meantime, Neff’s constant presence is sorely missed, Thompson said.

“He’s such a remarkable person,” Thompson said. “He’s clearly working so hard, and to see the progress he’s made — it’s really hopeful.”

Master Craftsmen

March 30, 2014

Tom Neff primarily works with large format film

More to Discover