An LSU researcher and her graduate students found excavations of an abandoned city in Belize, which offer a new view of how the Mayans perfected salt production, according to Heather Mckillop, a professor in the Department of Geography and Anthropology.

In recent research findings at Ta’ab Nuk Na in Belize, McKillop said she and her graduate students discovered salt works, where salt workers and residents of the village boiled brine in pots over fires to make salt.

McKillop has been traveling to Belize for archaeological research since 1979, and it isn’t coincidental that she found ancient saltworks in her work.

“I have carried out field research on the coast of Belize since I was a student,” McKillop said. “I have published four books, and many articles, and am active in being awarded grants for research.”

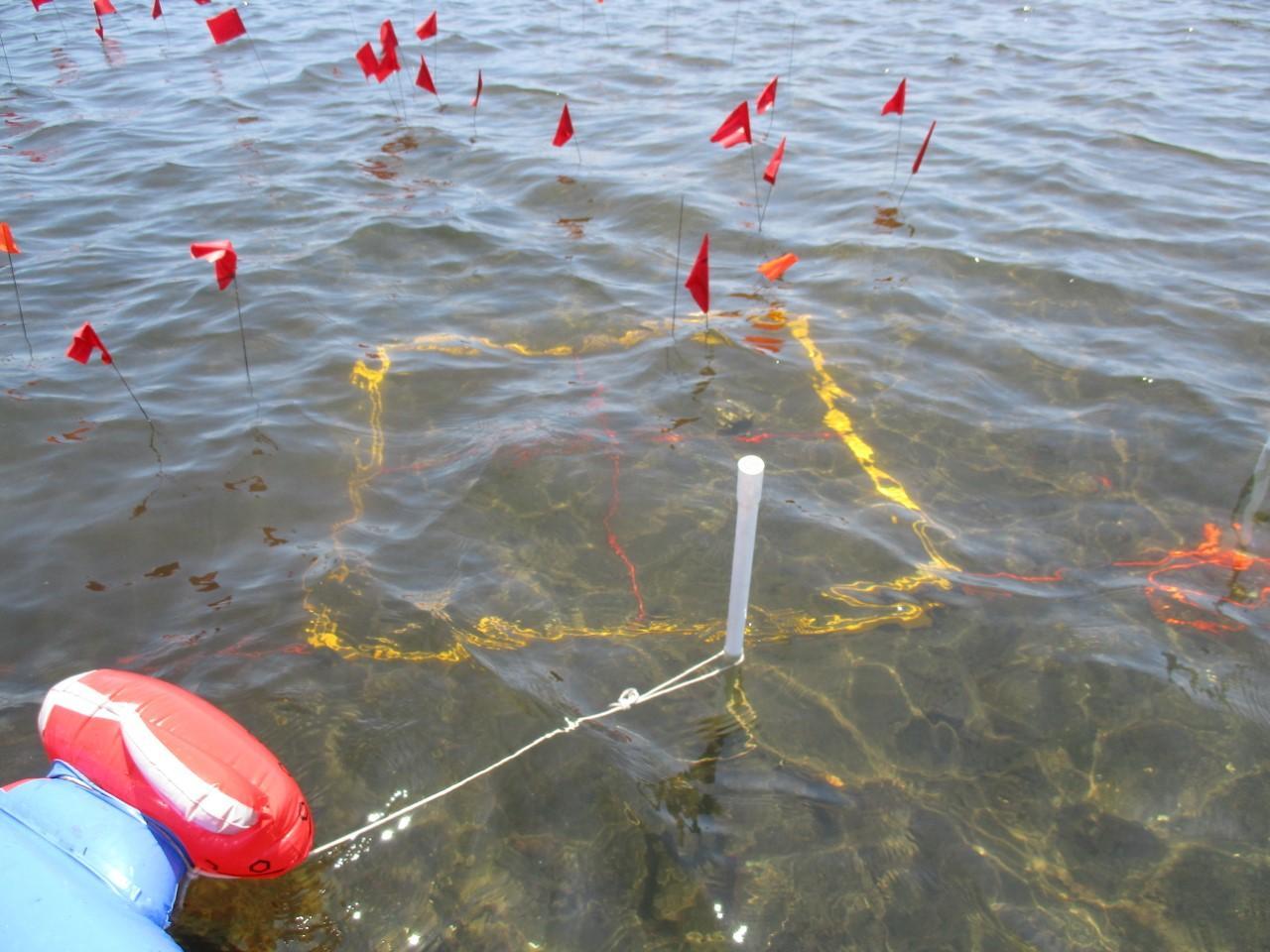

In 2004, with an LSU Faculty Research Grant and a small team of LSU graduate students, McKillop discovered ancient wooden buildings below the seafloor in mangrove peat, solid organic material that lacks oxygen to decay wood.

“I was able to apply for National Science Foundation funding to map, then begin excavating underwater sites,” McKillop said.

She received funding for her research and travels to Belize annually to find more discoveries.

Since 2004, McKillop and her graduate students have reported 4,042 mapped wooden posts marking the walls of buildings at 70 submerged sites. She published the findings regarding the ancient saltworks in her 2019 book, “Maya Salt Works.”

“This finding indicates a focus on the production of massive quantities of salt by Maya families who lived in the community and dedicated their time to making salt to transport to nearby inland Maya cities and towns where salt was lacking,” McKillop said.

McKillop’s discoveries demonstrate that ancient Mayans probably traded salt as salt cakes at inland marketplaces. She said this shows that the economy of the Mayans focused on the common Maya, who produced a surplus of salt.

While new discoveries show information never known to man, McKillop said that excavating ancient salt works is ongoing, long-term research. She will be applying for new grants to continue the research, preserve the waterlogged finds by 3D digital imaging and make 3D-printed replicas.

Since the saltworks were close to Mayan homes and were an important source of wealth, McKillop said that the ancient saltworks can be compared to family businesses in Louisiana.

“The [salt production] was all a family business,” McKillop said. “There are so many family-owned businesses in Louisiana that contribute to the economy. The idea that family-owned businesses such as the salt works could contribute so much to the Mayan economy is really interesting to me.”

Cheryl Foster, a doctoral candidate in the LSU Department of Geography and Anthropology, holds the Maya Research Assistantship and works in both the Digital Imaging and Visualization in Archaeology Lab and the Archaeology Lab.

Foster helps McKillop curate archaeological material and assists in various research projects. She also helps with teaching undergraduate and graduate students in both labs.

Prior to coming to LSU and joining the Underwater Maya Project, Foster participated in archaeological excavations at another ancient Maya site in Belize for three years.

“I joined the Underwater Maya Project in 2019 when we excavated at the large, underwater site of Ta’ab Nuk Na,” Foster said. “Due to the COVID pandemic, we were not able to return until this year, when we excavated another large underwater site with a larger team.”

Foster said the discovery that ancient Mayas were living at the salt works is important because it humanizes the process and shows the importance and intense specialization of making salt.

“Salt is a biological necessity,” Foster said. “However, most people likely don’t think about where their salt comes from. They buy it in the grocery store when they run out and don’t think any more of it. In the past, ancient peoples such as the ancient Maya had to procure their own salt or else specifically trade for it or buy it from merchants that specialized in salt production.”

While modern-day individuals might not think about where their salt comes from, Foster said that ancient salt production discoveries will help open people’s minds to the everyday struggles of earlier populations and our ancestors for basic necessities.

“This will lead to a better appreciation of the struggles still faced by people today who have to work to find salt, such as those affected by the Ukrainian-Russian war,” Foster said. “This has made salt a precious commodity in Ukraine, or people in impoverished communities who cannot buy salt conveniently.”

Foster said that there are plans to return again in spring 2023 for more excavations.

Geography and anthropology doctoral candidate Hollie Lincoln worked in Belize with McKillop this past spring. She said she’s been involved in archaeology in Belize for quite some time.

“In 2011 I started working in Belize, eventually getting my [Master of Science] in cultural resource management archaeology,” Lincoln said. “I didn’t want to give up Maya archaeology, so a Ph.D. specifically focused on ancient Maya Archaeology in Belize was the right next step for me.”

She said that while COVID-19 shut down travel for field work, 2022 ended up being her first field season in southern Belize with McKillop.

Lincoln said the recent discoveries of salt works bring awareness to the complexity of ancient civilizations that were previously unknown.

“I think people are always surprised to hear about how robust or organized ancient economies or ancient people were,” Lincoln said. “Just getting information like this out to the public on a broad scale means more people are made aware of something that they probably never thought to seek out.”