When I arrived at LSU in 2019 as a first-year history graduate student, I thought I knew what to expect. I knew I wouldn’t make much money. I knew that I would have to work hard and put in long hours reading, grading papers and writing essays.

But I was optimistic that LSU was the right place for me to pursue my intellectual and professional dreams. I thought I was attending a supportive university committed to keeping me and my fellow classmates safe and supported during our time in Baton Rouge.

While I’m still sure about the former, I’m no longer convinced of the latter. As I begin my fourth year as a tiger, I’ve become increasingly skeptical of the university’s commitment to me and my fellow students. After last fall’s Title IX scandal in the French Department, mishandling of sexual violence cases, dubious financial decisions and a potentially hazardous work environment, I’m now more cynical than ever of LSU’s commitments to the safety and well-being of the student body — but especially to its graduate students and teaching assistants.

Based on first-hand experience, the main reason for this suspicion is the dangerously high amount of deferred maintenance in Himes Hall, which houses history faculty on the second floor and graduate assistants on the third.

I first noticed it early in the fall 2020 semester. As is usual for Louisiana, August and September brought almost daily hard rainfall – so hard, apparently, that the roof became overwhelmed, causing water to flow into the attic space above the teaching assistant’s offices, eventually damaging the ceiling to the degree that sheetrock and insulation fell into workspaces below.

This happened several times, first in my office, which caused water damage to both school and personal property, and then to others’. Every time, maintenance would come — often painfully slowly — and patch the ceiling but not the root of the issue: the roof.

Later that same semester, I was on the second floor of Himes with another student in the waiting area outside of a few professors’ offices. He pointed out to me a sign, written on a piece of cardboard, covering an exposed area on the floor, inscribed “Warning: Asbestos.” We were both concerned.

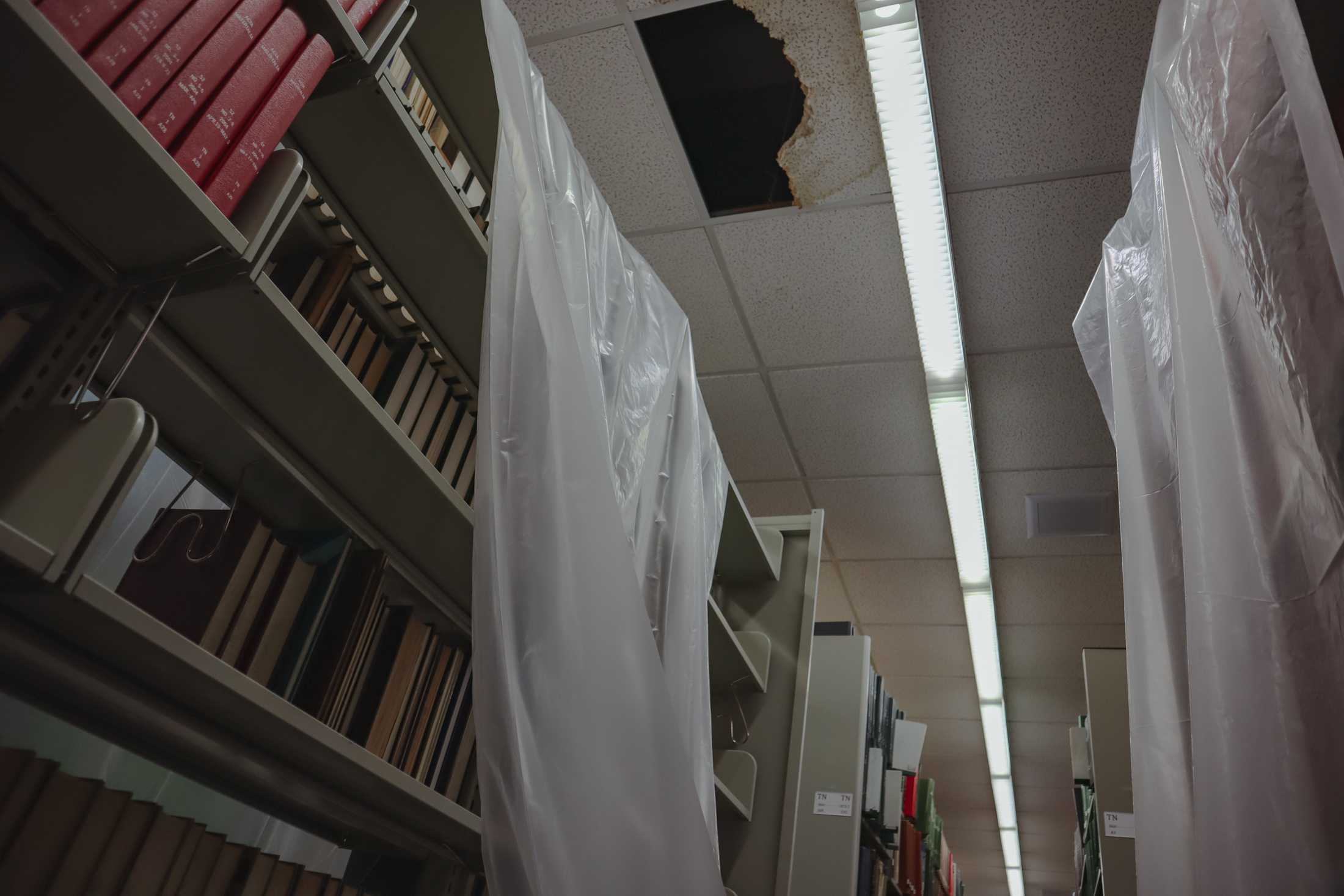

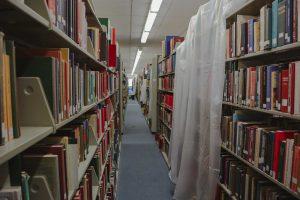

Since then, I’ve been increasingly disheartened by the state of the buildings in the Quad. Here are the two most explicit examples: Over the summer, the ceiling in Stubbs Hall leaked, forcing office furniture to find refuge in the hallway of the second floor, where it still sits. The second is one most of us already know: Many bookshelves on the fourth floor of the LSU Library are covered with tarps to protect the books – not as a short-term solution, but as a medium-to long-term one. They have been there at least a year.

Tammy Millican, the executive director of Facility and Property Oversight, told me that LSU is aware of these issues, is doing its best to keep up with the deferred maintenance and is complying with state and federal guidelines on the management of asbestos materials.

The large amounts of deferred maintenance, Millican said, is due to LSU’s large size and, in many cases, aging buildings. Since 2016, the state legislature has provided $2-3 million annually to address maintenance needs. On a more hopeful note, the backlog of deferred maintenance has been reduced since 2017, thanks in large part to the Strategic Capital Plan. According to Millican, “deferred maintenance will be lower than it was the previous year for the first time in many decades at LSU.”

This statement brings optimism, but we’ll see if it brings results. LSU’s recent spending habits have shown it doesn’t take these structural problems as seriously as it could.

According to LSU’s 2021 Comprehensive and Strategic Campus Master Plan, since 2017, the university has spent $120 million on major, nonacademic updates, such as an expansion of the University Recreation Building, Tiger Park Indoor Practice Facility and additions to the Football Operations Center.

Meanwhile, as students float down the UREC’s lazy river, a recent deferred maintenance budget shows that there are $1.2 million worth of repairs each to Himes and Coates Halls, $1.3 million in repairs each to Pleasant and Johnston Halls, and over $1 million in repairs to the library. In all, the budget reports a total of almost $604 million in deferred maintenance.

This misapplication of funds negatively impacts LSU in two important ways.

First, it shows where our school’s interest really lies: in athletics and non-academic fluff, instead of research, much-needed repairs and employee salaries.

Second, it harms our school’s future. Top prospective graduate students – who would all play a part in grading, advising and teaching undergraduates – are less likely to choose LSU over other schools when they see the signs warning of asbestos or water leaks and rotten sheetrock hanging over their heads. And what would they make of the tarp-covered library books? It would be difficult for one to conclude that LSU is a top academic destination when they can’t – or won’t – take care of essential research materials.

Thankfully, a university isn’t the sum of its administration’s policy decisions. It’s largely the makeup of the experiences and people that inhabit it. If my time in the History Department is indicative of the rest of the school, LSU has a lot of things going for it. We have kind, supportive, knowledgeable faculty members who demonstrate concern for students’ well-being.

Hopefully, the university will soon be mending its ways. New LSU executive vice president and vice provost Roy Haggerty has committed to several campus improvements, including an update to the library and an increase in graduate assistant pay, which is barely above the Louisiana poverty line for a single-person household.

Regardless of who the president was in years past, poor decisions were made. It’s the responsibility of the current administration to rectify those mistakes. To do so wouldn’t just be the bare minimum standard of care and duty, but it would also help LSU in the long-term. It would allow those of us who love this school and the people in it, mistakes and all, to be able to say honestly that LSU is the place to be to fulfill one’s personal and professional dreams.

Ben Haines is a 24-year-old history graduate student from Shreveport.