The LSU Library may be a far cry from the Great Library of Alexandria, but they share two notable qualities: an immense, diverse collection of human knowledge and a slow decline.

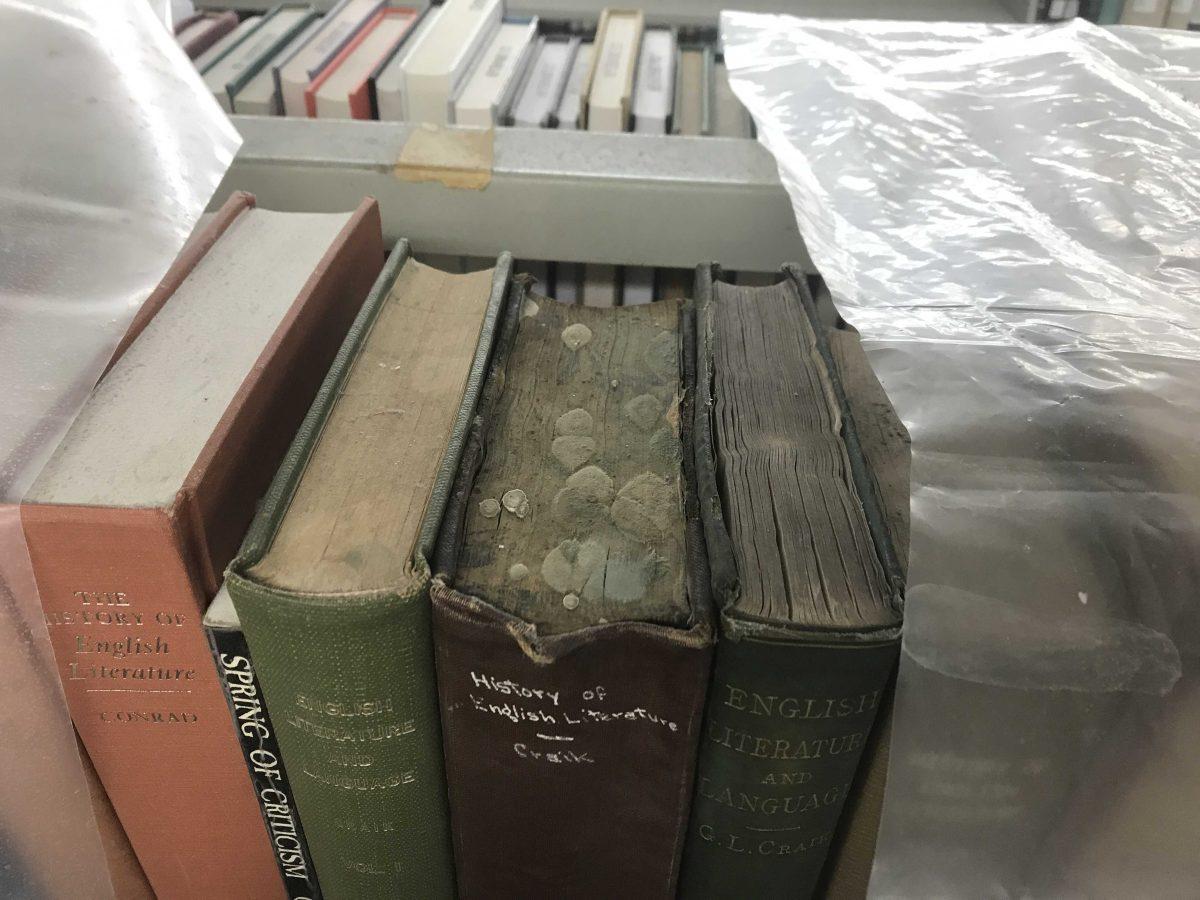

Since January 2020, 115 volumes have been damaged and removed from circulation after water leaked through the library’s decaying roof, according to LSU Libraries Director of Communication Marcela Reyes Ayala.

This phenomenon is reminiscent of basement flooding in 2018, which damaged the library’s microform collection—a stockpile of scaled-down, vintage documents that require specialized reading equipment. Replacing those specialized records may pose a unique challenge because most were “not issued by the Government Printing Office,” Reyes Ayala said.

The LSU Library is the modern progeny of the tradition that established the Great Library. Resting between the LSU Library’s brutalist exterior and asbestos-floored interior is an elaborate collection comprising 2.6 million volumes—more than half of the university’s entire collection. Like the Great Library before it, the collection includes disciplines ranging from the sciences to the arts in almost any language from almost any time period imaginable.

From the distinct microfilm referenced by Reyes Ayala to rows of academic journals, decades-old research and carefully-preserved pamphlets, there’s something for everyone at the LSU Library. For me, the accessibility of primary sources is an essential part of working through my senior thesis. When looking for essay sources as a junior, I left the library with more books than I ever intended or needed to use.

Walking and searching the third floor, I found Louisiana laws from the 19th and 20th centuries and original civil rights era pamphlets from both the progressive Southern Regional Council and the segregationist White Citizens’ Councils. The vast collection of knowledge at the heart of our campus beats even the most advanced Google search.

Although, on the fourth floor, 720,081 volumes that could benefit thousands of students from English majors to STEM minors are at risk of water damage. Protecting the information once coveted by the scholars of the Great Library—science, medicine, language—is a half-inch thick fiberboard ceiling and, of course, strategically-placed plastic sheets. Water leaking into the fourth floor of the LSU Library, like the fire that marked the beginning of the end of the Great Library, is a warning about the building’s future.

During the Alexandrine Civil War, Julius Caesar’s battle tactics unintentionally incinerated countless volumes—a calculated move that secured a military victory at an unfathomable cost. One could say the university makes a similarly calculated move by covering entire sections of the fourth floor with plastic while it carries out maintenance elsewhere. And yet, unlike Caesar, the university does not sit idle, unconcerned with the fate of the library.

“About 40 working hours were spent cleaning and drying out books that were affected by water,” Reyes Ayala said. “We also hired student workers who work in the stacks, and, since we reopened in August of 2020, we have hired three or four student workers who manage risk areas and shift books as needed.”

Tightly holding the university’s purse strings and long ambivalent about facilities maintenance, the Louisiana State Legislature truly makes the decisive, calculated moves that determine the library’s future.

Admittedly, the state’s refusal of funding is not as destructive as Caesar’s unplanned conflagration, but Caesar was an ancient general acting in the heat of battle. On the other hand, our modern state legislature, sworn to serve the public, refuses to act—or act against our interest—as they literally stare the problem in the face.

While the number of damaged volumes seems small, the state legislature’s neglect has an immeasurable cost.

“Keep in mind that ‘cost’ in financial terms is a narrow way of thinking about this,” Reyes Ayala emphasized. “LSU Library collections include invaluable and unique volumes that are difficult to quantify in monetary, cultural and historical value.”

Short-term political victories are not worth the risk of lost knowledge and impeded academic progress. The time, money, resources and effort that developed the LSU Library, unlike the Great Library, should not be diminished by the steady, avoidable decline of its collection.

The state legislature needs to realize that their Library of Alexandria is smoldering. If they refuse to act, they should at least tell their students and scholars to use—or save—the knowledge that’s left while they still can.

Drake Brignac is a 21-year-old political communication and political science senior from Baton Rouge.