When Southern University, Southeastern Louisiana University and LSU’s homecomings fell on the same weekend a few years ago, Paris Tate, a 21-year-old black and gay man, chose to celebrate in Tigerland — the quintessential hangout spot for young LSU students about a mile from Death Valley.

When he approached the entrance of Reggie’s, he said the doorman turned him away because he was wearing white shoes and earrings forbidden in the bar’s dress code.

“I was with a few friends, and when I found out I couldn’t get in, they didn’t go in,” Tate said. ”We all stood outside.”

Tate said he watched as the doorman allowed someone else wearing similar shoes into the bar—a young white man.

Tate grew up in Osyka, a rural Mississippi town of fewer than 500 people, which he said seeps with racism and homophobia. While visiting there last year, an older man drunkenly threw punches and shouted slurs at him during a house party where almost everyone was white.

When Tate was 12, he moved to Baton Rouge, where he said interracial and gay couples could be found seemingly everywhere — a drastic change from the social conservatism of his tight-knit hometown. He spent a year at Southeastern before taking time off of school to work, including a summer waiting tables in Osyka, before transferring to Baton Rouge Community College to pursue nursing.

“Baton Rouge has been very different from where I’m from and where I’m used to,” Tate said. “There’s a lot of diversity out here. I’ve seen more black and white couples out here than I’ve seen anywhere. I’ve seen more gay couples out here than I’ve seen anywhere.”

Tate said his Tigerland experience reminded him of the house party in Osyka where he was harassed for his race and sexual orientation.

“He tried to discriminate against me for being me,” Tate said. ”At Tigerland it was the same thing. I have white shoes on, I’m black, I have earrings on — so you’re not gonna let me in. You’re not going to accept me as a person.”

Many African-American patrons say dress codes in Tigerland target the black community by banning items deemed staples of black culture.

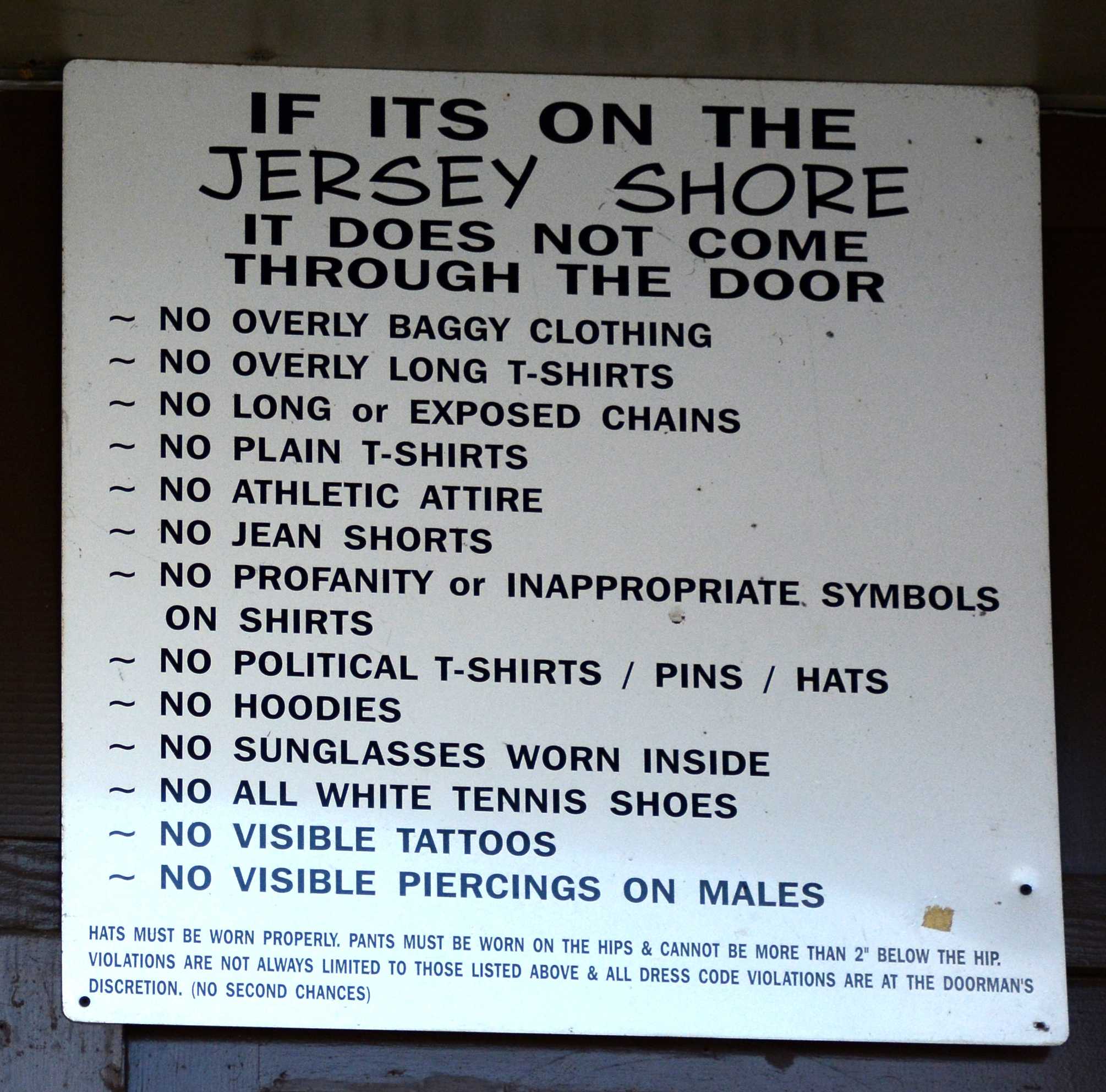

Reggie’s’ list of 13 prohibited items includes “overly” baggy clothing and long T-shirts, all-white tennis shoes, hoodies and jean shorts.

“I feel like they’re just letting in a certain stereotype,” Tate said. “If you don’t wear a plaid shirt and tight khaki shorts and boat shoes then you can’t get in.”

For Tate, Tigerland became a blemish on the otherwise diverse and accepting sheen of the Baton Rouge community, and he has refused to return to its row of bars since.

Darin Adams began working at Reggie’s in 1985, when it was named Sports. He was a doorman and bartender while also studying at LSU. He worked his way up to manager, and now owns Reggie’s.

He said the dress code has been around since roughly 1990.

Adams said Reggie’s has seen incidents of crime in the past — mainly people fighting, vandalizing and breaking into cars. After the Auburn University football day game on Sept. 19 at Tiger Stadium, he said someone broke into the bar.

The dress code aims to keep out troublemakers who will cause problems for his business, Adams said.

“We found that people who caused most of the problems weren’t the people that were wanting to come out. For instance, guys coming in gym shorts — this isn’t a gym,” Adams said. “If you’re coming out and going to a bar, you don’t dress like you’re in gym clothes.”

He said the rules are modeled after the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board’s dress code banning students from wearing anything affiliated with “tobacco, drugs, alcohol, illegal substances or violence or gang-related activities or exhibits profane or obscene language/gestures,” according to its policy. Hats, bandanas and do-rags are also banned, unless necessary for religious, medical or safety reasons.

“The dress code in bars in Tigerland definitely have an underlying ‘no n—–s allowed’ undertone,” LSU NAACP President Cimajie Best said in an email.

Best said Reggie’s’ rules are not consistently enforced across racial lines, and while no “sagging” is understandable, the bar should apply the rule to everyone — not just black people.

The last time Best saw a large number of black people at Tigerland was during a Kevin Gates concert at Mike’s in March, where she said some black ticketholders were denied access.

She pointed to deep-rooted racism as a motivation for Tigerland bars to keep out black people, although “belligerently drunk frat boys” and groups of “white boys” are the instigators of recent shootings and brawls.

Best said she would rather the bar print a “no coloreds allowed sign” on its doors.

“You can literally take one white boy and one black boy, dress them in the same outfit and watch the black boy be denied access,” Best said. “I’ve seen it happen.”

Representatives from Mike’s and Fred’s declined to be interviewed for this story, but Adams said tales of blacks and whites being treated differently at Reggie’s are a “fabrication.”

Adams said, statistically, most of the people Reggie’s turns away are white. He said black people constitute only 11 percent of the population — although 2010 U.S. Census Bureau data showed 32 percent of Louisianans were black, and more than half of Baton Rouge residents were black. Roughly 13 percent of U.S. citizens are black, according to the bureau’s 2013 report, the most recent year of available census data.

Adams said the bar turns away far more white people than black people, but “blacks just drop the race card because it’s easy.”

“We don’t let wife beaters in either,” Adams said. “I mean that’s for rednecks, which are mostly crackers. Now they don’t have a problem with that one. I mean, [African-Americans] pick and choose what they want.”

He said the black community feels “black lives matter and others don’t,” and black-on-black crime is far more of a problem than white police officers shooting black people.

Mike’s has a dress code similar to Reggie’s’. JL’s Place does not have a dress code posted outside, and could not be reached for this story.

Mike’s’ sign, posted on the wall outside of the bar, mandates that “Pants must be worn at the hip and not two inches below the hip.” It prohibits piercings, visible tattoos, white shoes and solid-colored or overly long T-shirts — all items Reggie’s also bans.

A note at the bottom of the sign reads, “All dress code violations are at the doorman’s discretion.” It also adds that the bar is a private establishment and reserves the right to refuse service to anyone.

Refusing service is illegal, however, if the bar applies its dress code to black people and not white people, said LSU Law professor Paul Baier.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits a place of public accommodation — an establishment that holds itself open to the public — from discriminating against people on “suspect lines” such as race, Baier said.

“There are laws and rules that govern this,” he said, “I don’t think I’ve seen any rules that say that a proprietor of a shop cannot lay down a rule that requires people to be well-dressed when they enter the door — that’s not one of these ‘suspect classifications.’”

While shop owners can lay down rules governing dress, they would violate federal law if they use the dress code as a tool to discriminate based on race, he said.

Using an allegedly equal rule to discriminate is known as “discrimination in fact,” he said.

Finance sophomore Mervin Delpit, who is black, said dress codes in Tigerland are part of a subconscious social phenomenon called micro-aggressions he sees across campus.

Micro-aggressions, sociology graduate student Tat Yau explained, are unconscious behaviors that express racism.

For instance, if someone automatically assumes a black person plays sports, they are unconsciously stereotyping them because of their race, Yau said.

He said Tigerland bars’ dress codes perpetuate micro-aggressions by targeting the African-American community.

“Let’s say you make a rule against hip-hop style clothing,” Yau said. “Who is more likely to wear the hip-hop style clothing? It’s African-Americans that are more likely to wear them, and you will disproportionately affect them.”

Delpit said he likes Reggie’s and enjoys its atmosphere, but he also notices an “overwhelming” number of white people there on any given night.

He said de facto segregation is evident in other areas of Baton Rouge, such as City Park, complete with a fence separating million dollar homes on Dalrymple Drive from the “hood.”

“But on campus it’s not like that,” Delpit said. “On campus, because you have a bunch of different Caucasian and African-American students from different places, it’s more subliminal stuff going on.”

Delpit said he has witnessed black people being turned away from Reggie’s for wearing white shoes, but if he was white and wore all-white Sperrys, he would probably be allowed in. While overt discrimination laws are mostly gone from American society, Delpit said, discrete racism persists in places like Reggie’s in the form of cost hikes or rules targeting the black community.

“This is not 1945,” he said. “They’ll either price you out of it, or it’s going to be political stuff like dress codes or policies that don’t allow us to come.”