The Louisiana Senate Select Committee on Women and Children held its third hearing on LSU’s mishandling of Title IX reports Thursday.

Here are five key takeaways from Thursday’s hearing:

General counsel explains why no one showed up

The committee invited nine current and former LSU employees to testify. None of them appeared in person, eight of them submitted letters and one did not respond at all: James Williams of the Board of Supervisors.

LSU General Counsel Winston DeCuir testified at the hearing. He said he decided to prevent all current employees from testifying due to the status of athletics administrator Sharon Lewis’ $50 million lawsuit against the school. He said it would be “inappropriate” or “unfair” for the employees to testify because they may be witnesses in the Lewis suit, in which she accuses LSU of gender discrimination, racial prejudice and a failure to follow Title IX policies stemming from the Les Miles era.

“In light of [the lawsuit],” he said, “I have to begin to take steps to defend the school. We owe it to our institution to do everything we can to defend it from claims. That’s my job as a lawyer.”

Sen. Beth Mizell asked DeCuir who would have testified, if not for the lawsuit. DeCuir said Williams, Executive Director for the Board, Jason Droddy and Board Member Remy Starns would have spoken. DeCuir said he could not speak for athletics department employees and whether they would have testified if not for the lawsuit.

Invited to the hearing from athletics were Head Coach Ed Orgeron, Athletic Director Scott Woodward, Executive Deputy AD Verge Ausberry and Senior Associate AD Miriam Segar. Williams, Ronnie Anderson, Droddy and Tom Skinner, former general counsel, were invited from the Board. The committee also invited Jennie Stewart from LSU Human Resources and Vicki Crochet from Taylor Porter law firm.

“This is a serious lawsuit,” DeCuir said. “It’s going to be a messy affair.”

Committee Chair Regina Barrow said that the committee has subpoena power to compel individuals to testify. At the previous hearing, the lawmakers wanted Orgeron to address the dispute over his alleged conversation with Gloria Scott, the 74-year-old Superdome worker who said Derrius Guice sexually harassed her.

Orgeron told Husch Blackwell that he never spoke to Scott. Then, he told the media that he “truthfully does not remember” speaking to her. In his letter to the committee, Orgeron said he does remember speaking to a representative of Scott. The representative told The Advocate that he never spoke to Orgeron, and Scott and her granddaughter told USA Today that she did speak to the coach.

“If it warrants someone being subpoenaed to come speak,” Barrow said, “we have the power to do that.”

Governor weighs in, disagrees with women lawmakers

Sen. Karen Carter Peterson explicitly called for the University to fire officials found responsible for wrongdoing. A sexual assault survivor herself, she said she wants to see accountability for a “cover-up at a lot of different levels.”

“I am confident that the system is going to change,” she said. “Heads need to roll. And we’re not going to just believe people’s written statements. They have to be answerable.”

In a Thursday press conference, Gov. John Bel Edwards said he agreed with LSU’s decisions to give Ausberry and Segar suspensions, saying that there were “institutional” failures above both employees.

“I accept that [Ausberry] didn’t properly report,” he said, “but there’s reason to believe he reported the way he was told to by his supervisor. In the grand scheme of things, do you terminate Mr. Ausberry? The president of LSU indicated to me that he didn’t think that that was warranted.”

Edwards said there’s no doubt that former LSU employees were responsible for “some of the most egregious behavior.” Former LSU president F. King Alexander resigned from the same position at Oregon State in March, and Miles was fired from his job as Kansas’ head football coach.

The governor said that lawmakers deserve to hear from LSU officials, such as Orgeron and Woodward.

“I think it would be very helpful and instructive to hear from them,” he said.

However, Edwards said the Lewis suit complicates the situation, and that Woodward said he would testify at the Thursday hearing, but that was before he had heard of the lawsuit. He said he doesn’t think it’s fair to say that LSU officials were unwilling to testify.

“I want members of the legislature, and I want members of the public to have as much information as possible directly from those who were involved,” Edwards said, “but whether that’s even now possible with the pending litigation, I’m just not sure.”

Did Ausberry and/or Segar violate their suspension?

Rep. Aimee Freeman said she heard from a University employee that one of the two LSU employees suspended after the Husch Blackwell report was released was doing LSU business while suspended. She said the person told her they did not want to speak at the hearing for fear of losing their job.

Executive Deputy Athletic Director Verge Ausberry was suspended for 30 days without pay and Senior Associate Athletic Director Miriam Segar was suspended for 21 days without pay. Both were supposed to undergo sexual violence training during their suspensions.

LSU suspended Ausberry after the Husch Blackwell report confirmed that a football player texted Ausberry, acknowledging that he punched his girlfriend in the stomach. Ausberry sat on the confession for months, while the player continued to abuse the woman.

LSU suspended Segar after Husch Blackwell found that she kept Derrius Guice’s name off a report of rape. USA Today reported that former Athletic Director Joe Alleva instructed his department to funnel all sexual violence complaints through Segar, a Title IX violation.

“While they were suspended, they were not supposed to be working, but we did expect them to send us any messages they did receive,” DeCuir said.

Freeman said LSU students asked her why other public universities let employees go in response to mishandling of sexual assault reports and LSU did not.

Former LSU President F. King Alexander resigned from Oregon State University after being put on probation amid investigations into his role in the University’s mishandling of sexual assault reports. Former LSU football coach Les Miles was fired from the University of Kansas for sexual assault allegations during his time at LSU.

No current LSU employee has been dismissed from the University in light of allegations.

“For the students, that feels very unacceptable. And I understand why they feel that way,” Freeman said.

In a later response to a similar question, DeCuir noted that this situation isn’t about one person doing something wrong and dismissing them, but instead that it is about “changing an entire system.”

Committee members discuss legislation

The committee members discussed several pieces of legislation they plan to present during the upcoming legislative session.

Freeman spoke about House Bill 375, a bill that she said she previously worked on with STAR (Sexual Trauma Awareness and Response). This bill would allow for victims of sexual assault to get out of a lease agreement if they need to.

“It’s really to protect students,” Freeman said.

Morgan Lamandre, the legal director at STAR, said victims typically want to go home after they have an experience with sexual assault, but sometimes they are unable to get out of a lease.

Freeman also spoke about House Bill 409, which involves training on mandatory reporting. Lamandre said that this bill makes it so that the sexual assault perpetrator is reported in the sexual assault reports. This would help to prevent repeat offenders.

Barrow spoke about a Senate bill that would create a Louisiana power-based violence review panel. She said one of the roles of this panel would be to serve as an advisory board to the legislature, governor and Board of Regents about power-based violence. Barrow said she would include college students on this board.

White spoke about a bill that would allow individuals to make financial contributions to STAR when they are filing their taxes.

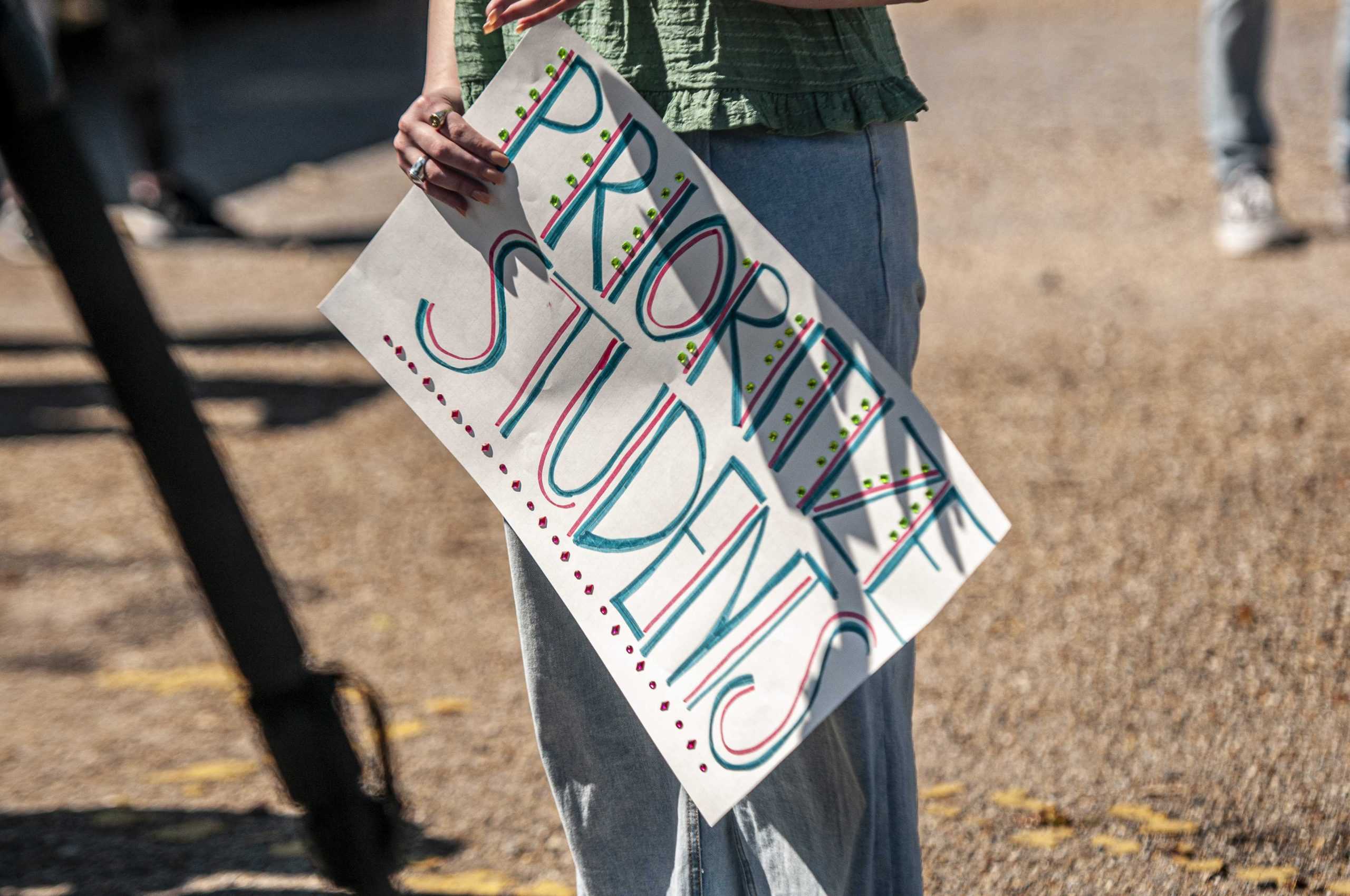

Students not satisfied

The first student to give testimony at the hearing was Kimsey Stewart, a second-year mass communication student.

“I’m here because the school that I love has chosen the athletic department over me,” she said.

Stewart grew emotional while she read a prepared statement. She told of a time just before the pandemic closed campus in 2020 where she witnessed a man peering in dorm room windows. She called LSUPD, she said, and the officer on the other end of the line told her that an officer could not come unless she stayed put in her room. No officers ultimately responded to the incident.

“I have thrived despite an institution that sees students as dollar signs and nothing more,” Stewart said.

Mass communications junior Mia LeJeune also testified. She echoed Stewart’s sentiment and called for more students involved in University decision making.

“I feel powerless,” she said. “What about us? Where is the fairness when it comes to students?”

LeJeune said LSU used to have blue-lit boxes around campus where students could report potential stalking crimes. In an effort to save money, she said, the school took down the boxes and created the “LSU Shield” app, which LeJeune and others called unreliable and dysfunctional.

LeJeune urged the lawmakers to continue to fund higher education despite the shortcomings of those tasked with running it. Cutting funds would hurt the students, she said, sapping financial support from departments that need it, like Title IX.

Mia Macaluso, secretary and social media manager of Tigers Against Sexual Assault (TASA), said she does not feel safe walking through campus, even during the day.

She said a few of her friends reported being stalked by a man, who LSU found guilty. The only punishment the perpetrator received, she said, was a ban from the UREC. Macaluso said it’s humiliating that her parents have to pay tuition to a school that won’t protect their daughter.

“The fact that a university this large could cover up something this large,” she said, “it is humiliating.”

Macaluso, Stewart and LeJeune said they were committed to changing that fact.

“The ultimate boss is the students,” Macaluso said. “We pay to be here.”