Facility Services workers at LSU are often seen but not heard. Students see them fixing lights, in dorm bathrooms cleaning showers or mowing the lawns outside. They keep the campus alive and functioning, and yet most students will never know their names or stories.

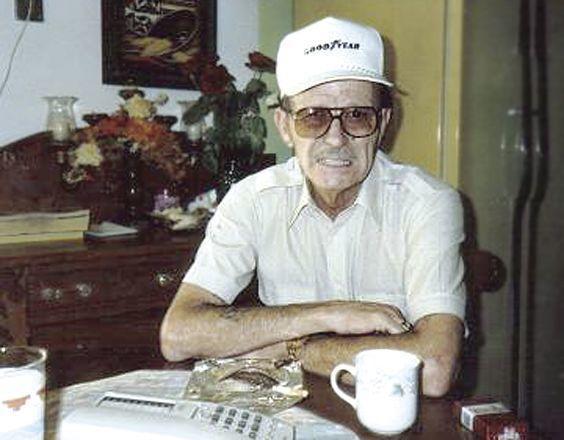

One Facility Services employee is 60-year-old James Poissot. He is a master carpenter and former teacher at Tara High School, where he worked with children of lower socioeconomic status. While working in the LSU Journalism Building, Poissot noticed a New York Times article about the 1964 arson murder of Frank Morris, an African-American shoe shop owner in Ferriday, Louisiana.

Poissot looked at the article on the wall, pointed and told the nearby receptionist that his father was one of the men responsible for Morris’ death.

“I walk by, and I see a picture of the gentleman my dad killed,” Poissot said. “And I did say it without any hesitations.”

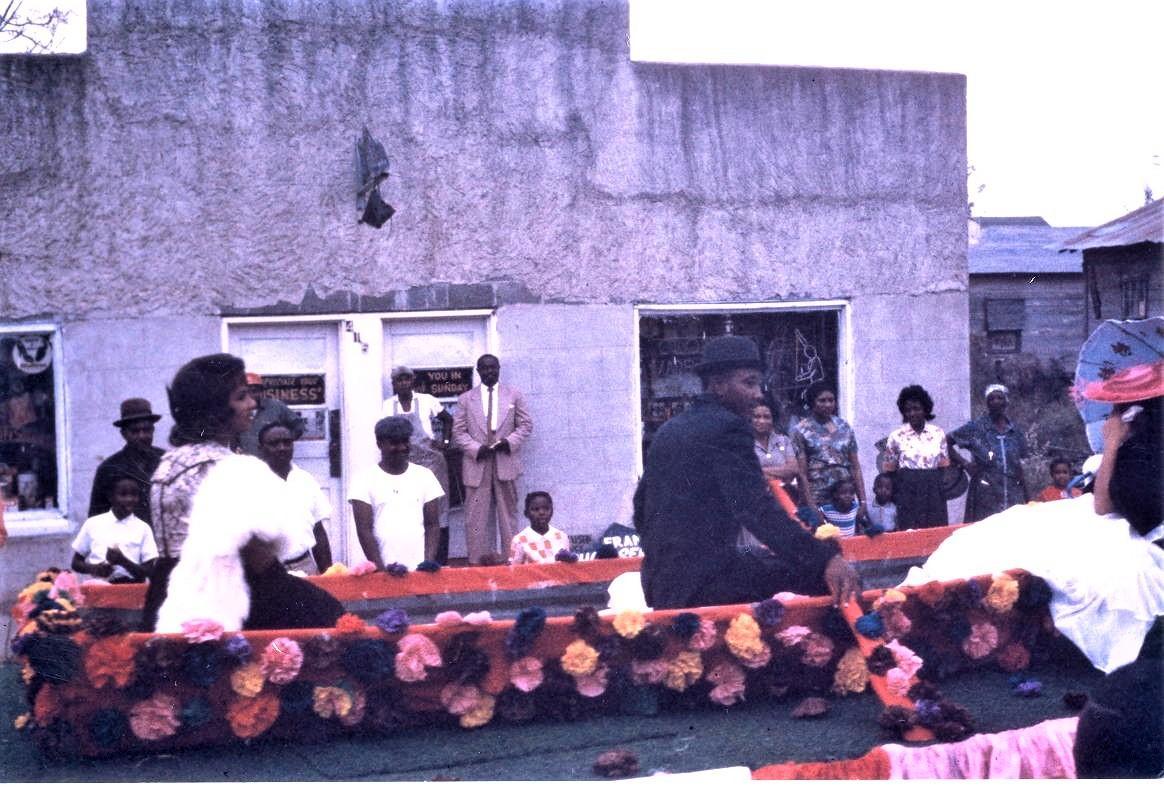

Frank Morris opened a shoe service shop in the 1930s in Ferriday, Louisiana, where he repaired shoes and saddles, sold jewelry, dyed purses and more. His business was known for being open to both black and white customers. Morris would deliver items to white women’s cars whenever they were uncomfortable with entering his shop.

As racial tensions grew in the state and the Ku Klux Klan developed strongholds on political figures and police forces, Morris’ shop became shrouded in false rumors that he allowed interracial couples to come at night.

It was on Dec. 10, 1964, when two white men burned his shop to the ground with Morris still inside. He escaped the shop with his entire body covered in burns but died four days later in the hospital.

The FBI opened and closed the case in 1965, 1967 and 2007 due to a lack of evidence. It was not until 2010 that Stanley Nelson, editor of the Concordia Sentinel, discovered that Concordia Parish Sheriff’s Deputy Frank DeLaughter organized the arson. Arthur Leonard Spencer and Coonie Poissot, James Poissot’s father, followed his orders and committed the crime.

Poissot’s father was riding with DeLaughter in his patrol car the night before the arson, according to FBI documents obtained by the LSU Cold Case Project. DeLaughter told Coonie Poissot that Morris needed “a good lacing [whipping]” because he refused to repair DeLaughter’s cowboy boots without a payment in advance. Poissot recruited Spencer to help him carry out the job, according to the Concordia Sentinel.

A Concordia Parish grand jury, led by a federal prosecutor, was convened in 2011. DeLaughter and Poissot were already dead by then, and no arrest warrants or indictments were ever issued.

Coonie Poissot spent his life in and out of prison with an addiction to amphetamines. He had numerous children in different states, many of whom James Poissot has never met.

Coonie Poissot died in 1992 without ever having a relationship with James.

James Poissot is, however, haunted by one event about his father that occurred before he left the family. One night, Coonie dragged James’ mother, who was pregnant at the time, into a forest and beat her to the point of miscarriage. He left her in the woods to fend for herself.

“I love my mom, and I miss her every day,” James said about his mother, who has since died. “She was always giving to people. I don’t like that he hurt my mom. He could’ve killed my mom; he didn’t take her to a hospital. No one deserves that.”

But after Coonie Poissot left, James Poissot learned to live a productive life under his mother’s guidance. He was born and raised with six siblings in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His mother worked at the sheriff’s office and was the highest-ranking female officer there. She took them to church every Sunday while supporting her family as a single mother.

“My mom taught us how to fish at the LSU Lakes,” he said. “We were catching supper, but she didn’t tell us that. We took care of our business.”

Poissot didn’t find out about his father’s past until the FBI interviewed his mother in the 2007 investigation of Frank Morris’ death and revealed the information from the 1960s declassified FBI documents.

He has accepted his estranged father’s past and is glad he did not lead a similar life.

“This is the flesh of my flesh and the bone of my bone, but this is not who I am,” Poissot said. “He chose his badge just as you choose yours. He set the stage. He set the bar.”

Not all sons of Klansmen are as fortunate, though. According to Concordia Sentinel editor Stanley Nelson, Arthur Leonard Spencer’s son, Boo Spencer, followed in his father’s footsteps as a racist and a criminal for most of his life, spending time in and out of prison.

“It’s amazing to me looking at the Klan households,” Nelson said. “How some [children] come out good and positive and live good lives, while others just can never get things going.”

In 2010, however, Spencer confessed to his father’s murder to the Concordia Sentinel in order to bring peace to the Morris family. Him and his father severed ties with one another until Leonard’s death two years later.

Poissot said the only reason he wishes his dad was a part of his life was for his grandchildren. He has three children and three grandchildren, one with cerebral palsy. He said he is inspired by his grandson’s bravery and believes his father missed out on the opportunity to see that for himself.

Poissot himself denounces racism and sees no reason to hate people based off their skin color.

“I think of my dad and I thank God that I was so far away from it,” Poissot said. “Some of the most cherished people that I loved the most in my life are not my color. So much hatred in this country. It’s wrong.”

Poissot feels no connection to his father or his actions. However, he still understands the pain and sorrow his father’s actions placed on the black families of Ferriday. He said his heart goes out to Morris’ surviving family.

Poissot dedicated his life to carpentry and feels incredibly passionate about the craft. He attended classes at the University to improve his skills. As technology developed, he forced himself to learn the necessary computer programs to succeed both in his career and in his University education. He continues to practice his craft as a Facility Services worker at the University.

Poissot doesn’t drink or smoke. He goes to church every Sunday and loves to watch shows on YouTube. His family history is dark and rich, while he strives to be accepting of all people.

“You’re going to see me around this campus,” Poissot said. “If you haven’t already, just in a blue shirt. We don’t know who we’re going to meet. We don’t know their stories. We don’t know where they come from.”

LSU Facility Services employee reveals father’s history as Ku Klux Klan member, accomplice in infamous murder

February 27, 2020

Frank Morris standing outside of his shoe shop.