When a 2019 research paper in Nature Magazine revealed high amounts of microplastic in the air in the Pryenees mountains, LSU chemical engineering professors Kalliat Valsaraj and Bhuvnesh Bharti became intrigued.

“This is a remote place — they shouldn’t be there,” Bharti said. “We started digging into this topic further and further, and we realized that in the last seven or eight years, microplastics have been detected in so many oceans and water bodies; they are kind of ubiquitous.”

Microplastics are defined as pieces of plastic smaller than a fifth of an inch. When plastic waste is thrown into the environment, sunlight degrades the plastics over time, a process known as photooxidation. As the plastics degrade, microplastic is formed, and it has the potential to be transported into the air by wind.

Bharti said these micro-scale pieces of plastic can be potentially harmful, but not much is known about their characteristics, how long they take to form or their implications for human health.

Valsaraj and Bharti received a two-year research grant from the National Science Foundation Chemistry Division to further explore this subject.

Through their research, Bharti and Valsaraj aim to find out how microplastic is generated from plastic waste, how long this process takes and what the characteristics of microplastic are.

Previously, scientists thought plastics would degrade into their elemental composition, such as carbon dioxide or water, and thereby become harmless.

But recent research has revealed that these plastics can remain in the environment and the air for longer than expected.

“The general thought was that most plastics would be biodegradable — that there was some organism out there that would consume it and transform it into their elemental compositions,” Valsaraj said. “But that has not been the case. We are finding that they don’t degrade to their elemental composition, they remain as tiny plastics in the environment for long periods of time.”

Plastic is typically hydrophobic, meaning it repels water. As the plastics degrade, however, they become hydrophilic, or “water-loving” according to Valsaraj.

From there, the microplastic has the potential to be transported into the air by surface winds. Some of these microplastics can be inhaled by humans, but the health consequences are not yet known.

“Intuitively, I would say that ingesting microplastics is not good for our health, but we don’t know how microplastics interact with our various organs,” Valsaraj said. “We don’t know enough about the health consequences yet to say that ingesting this much is going to create this problem or whatever.”

Understanding the characteristics of microplastics, such as whether the particles are clumped together or more dispersed, will have significant consequences for how these materials affect public health.

“Our research would tell them exactly what these particle sizes and characteristics are,” Valsaraj said. “Then, scientists can figure out how it affects our lungs, our kidneys and our liver.”

Bharti said this could potentially impact the future of plastics, including which plastics to use and which not to use.

“We can have certain studies present that can actually allow these companies and even regulatory bodies to regulate which plastics companies use,” Bharti said.

The first stage of the research will involve putting different pure plastics in a reactor and observing how they change over time in different conditions.

“We are going to do some very preliminary experiments on certain types of plastics in a reactor and over time we will be able to figure out how much and at what rate these plastics degrade, and what will be the final product that results from this,” Valsaraj said.

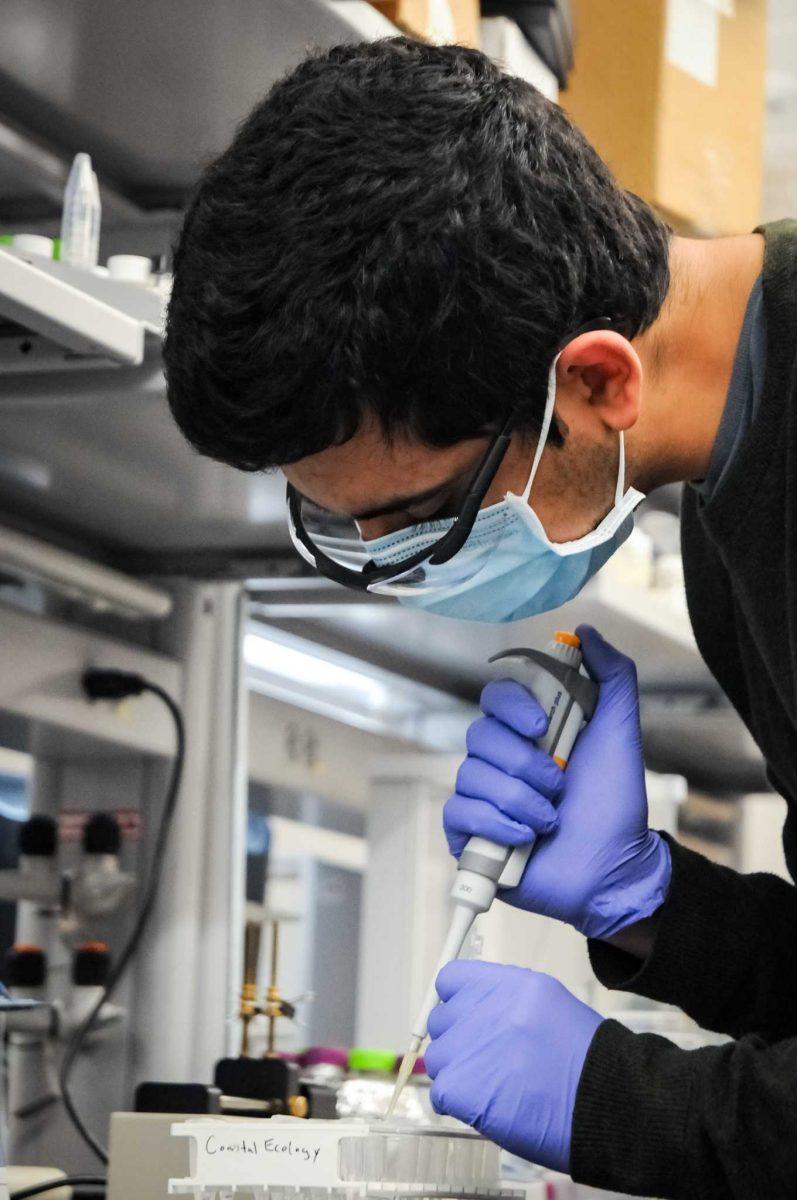

Chemical engineering graduate student Ahmed Al Harraq said the reactor will effectively simulate the role of the sun in photooxidating plastics. Al Harraq will be conducting experiments in the lab for further research.

“The reactor has a lamp that radiates whatever is inside the chamber, and you can then program the radiation to simulate what the sun radiation would be in say six months; you could achieve that in a week in the lab,” Al Harraq said.

Since the field of microplastics is relatively new, Bharti and Valsaraj’s study could provide valuable insight into how these plastics are formed and thereby aid future research into the public health and environmental consequences of microplastic pollution.

“NSF recognized the importance and immediate need to investigate this topic. Kalliat and I had been talking about this field and the potential upcoming issues with microplastics,” Bharti said. “It’s great to see that NSF saw value in our idea and were willing to support our research.”