The discovery of light fluctuations coming from KIC 8462852, colloquially known as Tabby’s star, caused quite a stir in the astronomy community.

One theory for the cause of the dimming involved an alien megastructure known as a Dyson sphere. However, when the Kepler Space Telescope, which had previously observed the star, changed directions, astronomers lost their main resource for studying the star.

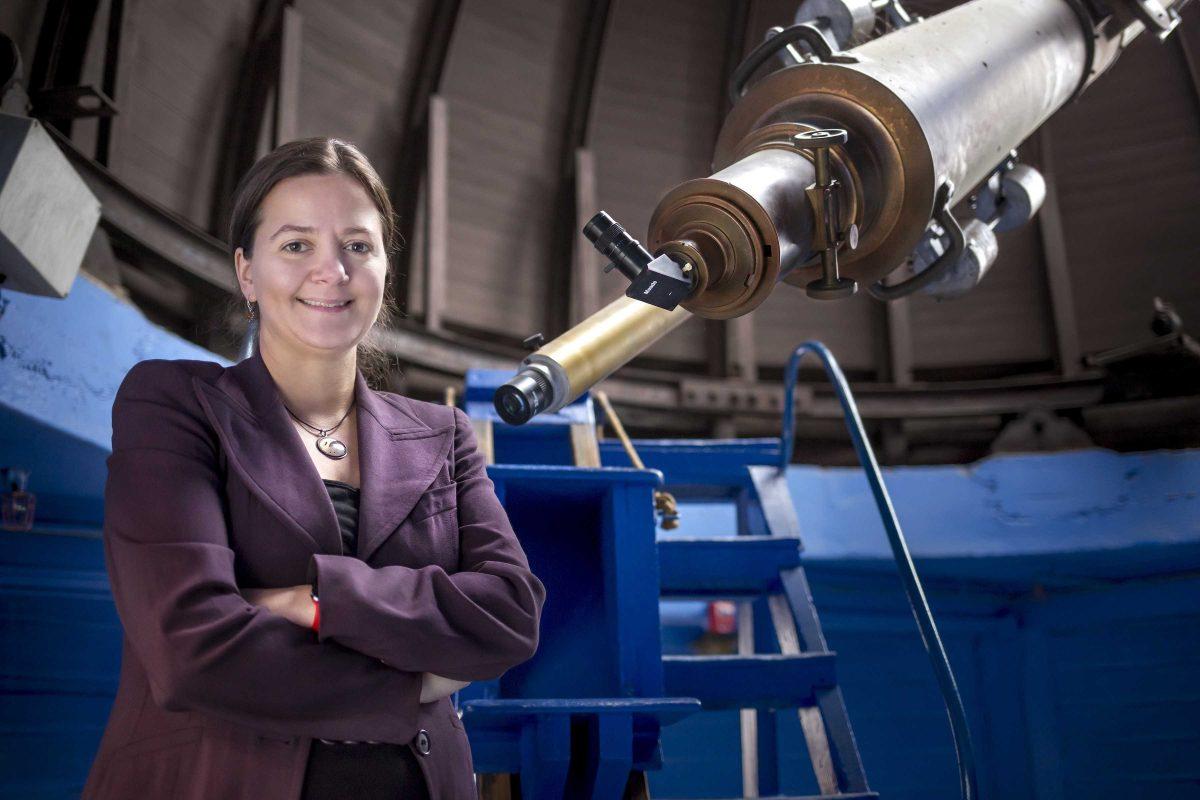

LSU Department of Physics & Astronomy assistant professor Tabetha Boyajian created a Kickstarter campaign in May 2016 to fund the Las Cumbres Observatory in Goleta, California to observe the star.

By the end of the campaign, Boyajian raised over $100,000 from over 1,700 backers. Boyajian said the success of the campaign was particularly surprising as this crowdfunding of science hadn’t really been

attempted before.

“I attribute it to luck,” Boyajian said. “This is kind of the first one of its kind to do something like that. This was a way for people who had a couple extra bucks to contribute to science, which we thought was pretty cool.”

Using the funds, the Las Cumbres Observatory observed the star from March 2016 to December 2017. The observatory gifted the program 200 hours of observing time before the Kickstarter began.

However, when astronomers received data from the Las Cumbres Observatory, they realized that the dimming could not be caused by an alien megastructure. The dimming events were more likely caused by a cloud of dust.

While the severity of the dimming events ruled out the possibility of them being caused by a planet, another detail ruled out the alien megastructure theory. Boyajian and other astronomers noticed different wavelengths of light were being blocked by varying degrees. Since an opaque object like an alien megastructure blocks all light equally, this theory would not work.

For the first few months of 2018, Tabby’s star was not visible due to the Earth’s revolution around the sun. In March, Las Cumbres Observatory continued its observation of the star and has now observed two new instances of dimming, the largest since the star was observed by Kepler. However, these dips were still somewhat small in comparison to the largest dip observed by Kepler of 20 percent.

Going forward, Boyajian said the project will focus on the wavelengths of light being blocked to determine what the dust cloud comprises.

“We’re viewing it in a few different colors,” Boyajian said. “How much the star’s light is blocked in a certain color can tell us the kind of composition and the particle size of whatever it is that’s doing the blocking.”

Although astronomers still do not know a lot about what is causing the dimming, Boyajian said these things take time.

“We can’t really predict anything the star is doing, and that’s what makes it so interesting,” Boyajian said. “We don’t know when these things are going to happen, what they are going to look like and how long they last. We’re waiting on one of those big 20-percenters, but it may never come. Next month we may get five of them in a row.”