Standing like a monument to LSU’s international history, a live oak on Dalrymple Drive shadows a plaque dedicating the tree in honor of Latin American revolutionary Simon Bolivar.

The Venezuelan Student Association bought the plaque in 1983, when the association’s 178 students made it the third-largest international student group behind Malaysia and Vietnam.

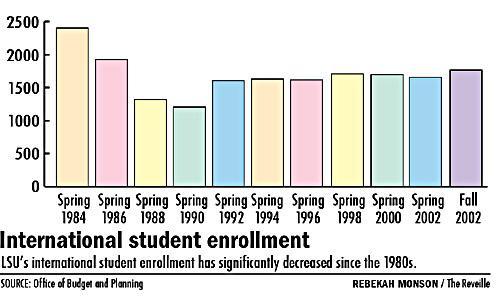

1983 stands out as a pivotal year, a year in which LSU’s international student population peaked at 2,400 students.

By fall 1988, however, that number dropped by half to little more than 1,200. In the 15 subsequent years, the population rose slowly to its total of 1,764 students, according to data from the Office of Budget and Planning.

Total Latin American students numbered less than 300 in 2003. As a result of declining numbers, the Venezuelan Student Association has not held meetings for the last three years.

Most faculty and administrators agreed three converging local and international factors influenced the decline and continue to determine the international student population — international crises in countries like Iran and Venezuela, consecutive tuition rate increases and the absence of a committed University recruitment program.

Although the University increased its total number of international students last year by 3.9 percent, it lags behind national trends, failing to meet the national average increase of 6.4 percent for the second straight year, an Institute of International Education survey indicates.

Unlike LSU’s steep decline during the 1980s, national figures have increased steadily since 1981, said Heidi Reinholdt, manager of publications and editorial projects for IIE.

In the late 1970s, LSU’s English Language Orientation Program — a first-step English language training program for professionals and students — had one of the highest student populations in the country, said ELOP director Margaret Jo Borland.

Venezuela and Iran, two main “feeder” countries, supplied most of the students in the ELOP, but both countries suffered convulsing crises that reduced the number of students each country sent to LSU.

When the Iranian Revolution took place in 1979, instating the Ayatollah Khomeini in power, LSU lost its entire Iranian population, Borland said.

“Iranians were not granted visas by the U.S. State Department,” she said. “No one. The state department turned it into a flatline situation.”

As late as 1983, 129 Iranians attended LSU, but by 2003, that total dwindled to four.

Hassan Marzoughi, who holds a master’s degree in economics and taught at the Ministry of Cooperatives in Tehran, Iran, said getting a visa was nearly impossible. After four trips to the United Arab Emirates last year, he finally got his visa.

Borland said at the same time as the Iranian revolution, the first of the Venezuelan crises occurred.

Gustavo Douaihi, a geology senior from Venezuela, said the 1983 “Black Friday” market crash in Venezuela hurt the international student population immensely. Before the crash, one American dollar equaled 4.3 bolivares, but the exchange rate jumped to 7.5 bolivares on that day, nearly doubling the price of a United States education in less than 24 hours.

By 1988, the exchange rate had climbed to 30 bolivares. It jumped to 170 in 1995, to 470 in 1998, and to 1,600 bolivares at present.

Fewer and fewer parents could afford to send their children to the United States, said Vilma Calhoun, a 1978 LSU graduate and former employee at International Services Office.

Venezuelan students totaled 172 in 1983, compared to 138 Indian students. Today, the 378 Indian students outnumber Venezuelan students eight to one.

Tuition increases compounded the problem. Nonresident tuition tripled during the 1980s.

Julius Langlinais, associate dean of the College of Engineering, said in the early 1980s the Louisiana Legislature mandated the tuition hikes. International students also had to pay out-of-state tuition fees, which had been waived before.

“Fifteen years ago it was a fairly decent bargain for a student to come here,” Langlinais said.

Hoffman said the move by the Legislature made it difficult for international students to attend.

International students in 1980 would pay only the resident tuition rate of $564, which in Venezuela would be about 2,256 bolivares. By the end of the 1980s, tuition rates and out-of-state fees amounted to $5,037, the Venezuelan equivalent in 1988 of 150,000 bolivares.

“Historically, LSU recruited middle-class families who could afford to send their children to LSU,” Hoffman said. “The really wealthy would send their children to Ivy League schools anyway.”

The competition among universities to recruit international students puts the University in a difficult situation.

Frank Cartledge, associate dean in the chemistry department, said the University has no recruitment program for graduate or undergraduate international students. Any recruiting is done on a case-by-case basis, he said.

Several faculty members and former administrators said LSU could do more to live up to its Strategic Plan by actively recruiting and offering more financial assistance to these international students.

The Strategic Plan states LSU must make the most of its attributes like Louisiana’s culture, history and strategic relation to the Caribbean and South America.

Calhoun said only genuine efforts toward the goal of increasing international student enrollment would improve the number of international students.

Hoffman said LSU faculty have not maintained their connections with students and administrators outside the United States.

“We’ve never had a ‘full-court press’ for recruiting international students in the first place,” he said. “Maybe during the Good Neighbor policy, but that’s the exception.”

He said faculty who have connections in other countries could recruit from those countries even now.

An example is Kevork Mardirossian, a music professor from Bulgaria who has increased the number of international students in the School of Music by recruiting when he travels overseas to perform concerts.

Brad Brumfield, who is in the Saudi academic unit for ARAMCO Service Company, said many universities have set up recruiting offices in the Middle East. Because of LSU’s strong engineering program, Arab countries have strong ties with the University, he said.

But Cartledge said LSU’s lack of funds reduces its ability to compete with other universities.

Langlinais agreed.

“The vast majority of graduate students are motivated by assistantships,” he said. “How much money you have available in assistantships determines how many international students you have.”

Calhoun said international students are more of an investment, saying the amount of money the students bring to the community is staggering.

According to data by the National Association for Foreign Student Affairs, international students contributed $23 million to the Baton Rouge economy last year. The University of Florida’s 3,884 international students contributed more than $60 million to the Gainesville economy.

Langlinais said the profit picture is not the same for a city as it is for a university. Revenue in the private sector does not contribute to a university’s economic situation.

The state assumes in-state students, by virtue of their parents’ taxes, will pay for most of their higher education, he said. The logic is that because out-of-state and international students do not pay Louisiana taxes, they do not contribute to the public education and should pay more than Louisiana residents.

“The state foots the entire bill for international students,” he said.

Calhoun said critics overlook the fact that students’ parents spend enough money in Baton Rouge to make up for the difference just by bringing their family and staying in hotels.

“In May, seven to 10 Honduran students will graduate,” Calhoun said. “All their families will visit, stay in hotels, rent cars, eat at restaurants. They will leave thousands of dollars in Baton Rouge.”

For example, Douaihi told his parents he did not want to walk this year at his graduation. He said his parents were appalled. They paid all his tuition, and they were going to see something to show for it, he said.

Hoffman said the University should promote diversity and provide a unique learning experience.

“The difficulty is that people say we’re not in the business of subsidizing students from out of state, whether it be Texas, Mississippi, Chile or Argentina,” he said. “Our mission statement is for the Louisiana community. Taxpayers are footing the bill.”

Natalie Rigby, director of the International Services Office, said they are happy with the number of international students at LSU. Although the University does not recruit, many of the students who apply end up here, she said.

“It’s a healthy number,” Rigby said. “But we’re always looking to be more global.”

International void

May 9, 2003

International void