New Year’s in New Orleans. Set to be just like any other year, the city was full of joy and life. That was all until a moment. An attack that shook New Orleans and Louisiana to its core.

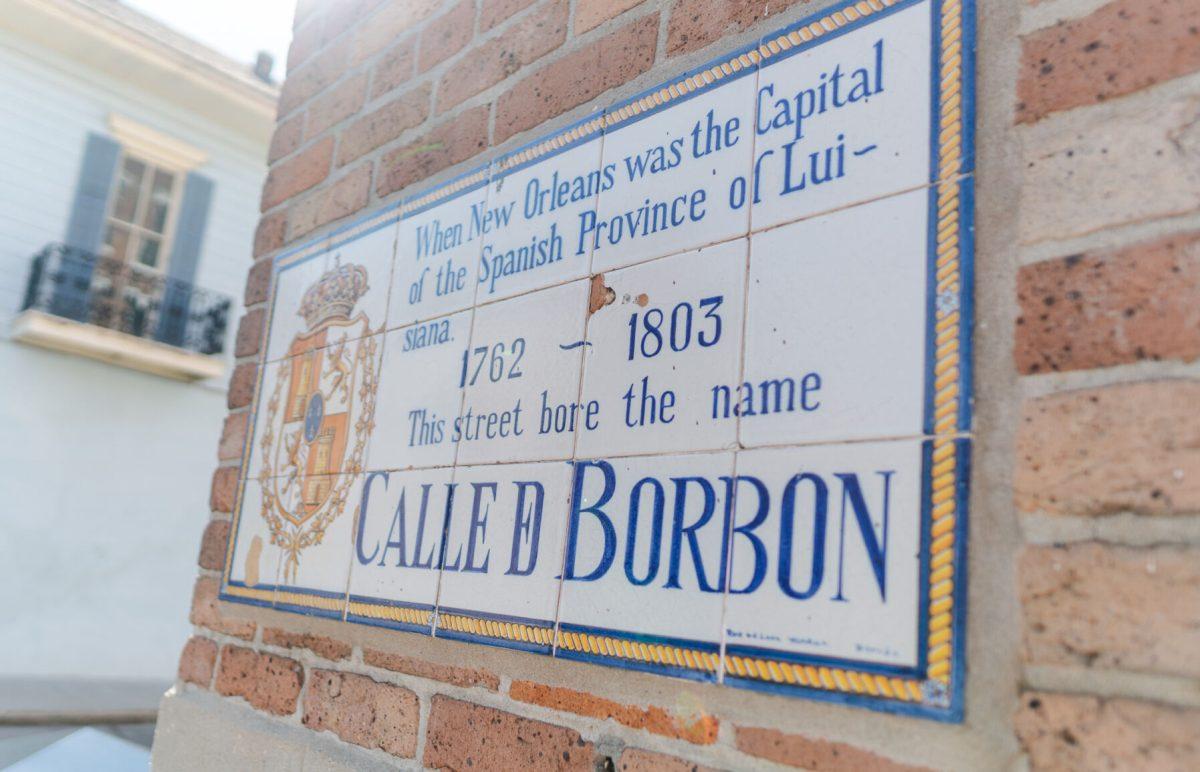

For the first time in recent memory, there was a terrorist attack in the heart of the city. On New Year’s Day, a little after 3 a.m., a man drove a truck through crowded Bourbon Street, exited the vehicle and fired his gun into the crowd.

Fourteen people were killed, and at least 57 people were injured. The FBI’s website says there were approximately 136 victims in total, with the investigation still ongoing.

Following the attack, it emerged that some of this tragedy could have been avoided. The street’s bollards, barriers used to stop cars, were disarmed the night of the attack.

In 2016, Nice, France was attacked. A 19-ton cargo truck rammed into the streets on Bastille Day, killing 86 people and injuring 434 more. After that attack, the City of New Orleans took note and spent $40 million to put safeguards in place. The bollards were supposed to go up every night to protect pedestrians.

On Jan. 1 of this year, most of the bollards were missing or not working. The city was in the process of replacing them in preparation for the Super Bowl. The New York Times shared the report and mapping of how many barriers were not working that night.

The lawsuit

Now, survivors of the attack are suing New Orleans for damages after it was revealed the city was notified there was a high risk for a terrorist attack in a report published in 2019. The plaintiffs include attack victims Corian Evans, Alexis Windham, Justin Brown, Gregory Townsend, Shara Frison and father of the deceased Brandon Taylor, Joseph Taylor.

The City of New Orleans, Hard Rock Construction, Travelers Excess and Surplus Lines Company are named in the lawsuit, but the development, engineering and management consulting company Mott MacDonald is the main focus.

The lawsuit calls the injuries and deaths of Jan. 1 tragic, but preventable, and alleges that every defendant in this case was notified of detailed explanations of risks they could’ve taken action on to improve public safety.

“This isn’t just the story of a bad plan, though,” the lawsuit reads. “There is also bad execution. City contractors failed to live up to contractual obligations and perform work in the order and manner specified.”

The history of knowledge surrounding the risk of an attack is laid out in the lawsuit. It first references a report New Orleans contracted from the construction company AECOM that said the French Quarter is at risk of a mass casualty incident.

In 2018, bollards were up and running on Bourbon Street. Less than a year after the implementation, issues with the bollards came to light, with many being disabled from beads, spilled drinks, rain and other contaminants.

In 2019, the French Quarter Management District requested Interfor International create a study assessing possible safety concerns with the current system. The report found safety risks, of which it notified the city.

“The risk of terrorism – specifically mass shooting and vehicular attacks – remains highly possible while moderately probable,” Interfor’s 2019 report reads.

Later, the report says the bollard system doesn’t work, with the recommendation that the barriers be fixed immediately. The lawsuit documents that Mott MacDonald saw issues with its design, specifically that the system did not protect pedestrian walkways.

The attempt to replace the bollards recently was noted, but the lawsuit said Mott MacDonald is at fault for not putting temporary protection in place.

“Mott MacDonald seemingly did not think it prudent – or negligently failed to recommend – a system that would protect the sidewalks of Bourbon Street from a vehicle attack,” the lawsuit reads.

The suit notes temporary or working barriers were not used on the day of the attack.

Matthew D. Hemmer, the lawyer representing the plaintiffs, explained how this attack has affected his clients. Hemmer explained his job is to “find out not only who is responsible, but why. That’s important because it prevents things like this from happening again, and it also lets you fix the reasons that led to it.”

Originally there were seven plaintiffs in the case, but after the filing, more victims are joining the lawsuit. As for what the plaintiffs were looking for, Hemmer said the suit isn’t about the money, and that most of the victims are looking for answers.

“This is something they are going to live with for the rest of their lives,” Hemmer said. “And I think they want to know why they are going to carry this burden with them.”

Some victims want to make sure this incident isn’t repeated, and others are looking to relieve the massive medical bill and the lost income that they will be facing in the coming months and years.

Hemmer talked about the evidence shown in the lawsuit, alleging Mott MacDonald and others knew the risk posed to Bourbon Street.

“In 2019, we knew this is a plan torn directly out of the ISIS playbook. From that time on, when you look at the terror weapon of choice of these monsters, it’s vehicle ramming attacks.”

The lawsuit also states Mott MacDonald knew and used Ford F-150s, a similar model to the Ford truck that was used in the attack, as an example of cars that could pass the bollards. The suit alleges the consulting firm knew about the bollards’ dangers back in April of 2024, and the same car they used as an example manifested less than a year later.

“When you’re talking about what someone who’s supposed to be a worldwide expert in the field,” Hemmer said, “I can’t think of any good reason why that could not have been entirely foreseeable and preventable.”

In Hemmer’s opinion, the City of New Orleans trusted Mott MacDonald, a well-known and trusted global company, and the company failed the city. He sees that the city did the best it could do, and he said he was bothered to see how much these companies were paid only to provide subpar protection.

In the transitional period for the bollards, the companies were to take out the bollards that could stop 15,000-pound vehicles driving 40 miles per hour. Their plan was to replace them with ones that can stop 5,000-pound vehicles going at 10 miles per hour.

Hemmer hopes in the aftermath of the attack the city moves away from the original plan and puts up stronger bollards.

Currently, Hemmer and his team are working on filing an intervention to add more plaintiffs to the lawsuit. Hemmer says that he feels very confident about the future of this case.

“Big tragedies are rarely the result of one bad decision…” Hemmer said. “When you have something like this, there’s so many opportunities for the problems to get fixed, for better plans to be made, for corrections to be made for something like this to happen. There had to be a lot of bad decisions, and a lot of missed opportunities.”

Mott MacDonald, Hard Rock Construction and the City of New Orleans did not respond to requests for comments.