It’s time for LSU and the NCAA to step up their drug-testing game.

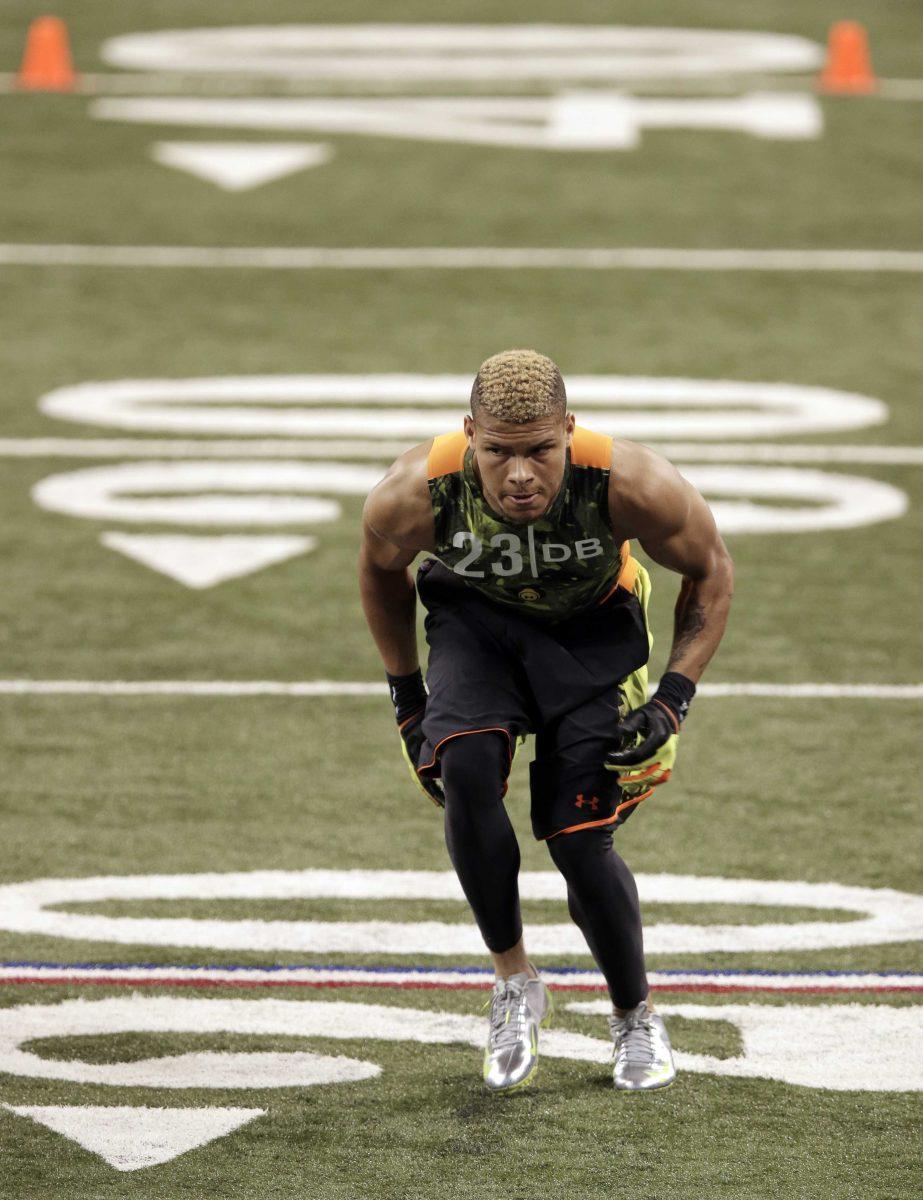

A report surfaced last week in which an anonymous NFL assistant coach told USA Today’s Jarrett Bell that former LSU defensive back Tyrann Mathieu responded to a question about how many failed drug tests he had in college before he was suspended with, “I quit counting at 10. I really don’t know.”

Ruh roh.

I’m not saying the report is true, but drug testing is a big deal when it comes to collegiate athletics. Not the fact that Mathieu was using illegal drugs, but that he failed drug tests over and over and little was done about it before he was booted from the LSU football team last August.

Mathieu went on record rebutting the report in a statement released Friday, “I would expect that conversations regarding my drug testing history during the course of my medical treatment would be private. LSU has a strong drug testing-program, and LSU went to great lengths to help me in my treatment and recovery.”

When I read Bell’s report, I decided to do some digging into both the NCAA’s and LSU’s drug testing enforcement policies.

As it turns out, the NCAA pulls a Pontius Pilate when it comes to enforcing drug testing on a school-by-school basis; it leaves it up to its member institutions to establish drug-testing policies.

According to the NCAA website, “Testing programs are not governed by the NCAA, and schools are not required to release results of the institutionally administered drug test, but they are required to enforce their own policies.”

It sounds like colleges can put in place whatever kind of drug-testing policies they want, and the NCAA can’t do anything about it.

In the 2011-12 season, there were more than 450,000 NCAA student-athletes among all classifications, yet the NCAA only has two programs for testing student athletes.

Approximately 2,500 athletes are tested at least once every five years at the NCAA Championships in all divisions, with some championships being tested every season for performance-enhancing drugs and street drugs.

The second source of NCAA testing involves its year-round program where 11,500 student-athletes across all sports are randomly tested for performance-enhancing drugs, but not street drugs.

I’m no math major, but I crunched the numbers on the proportion of student-athletes being tested: A whopping 3 percent of student-athletes are tested annually by the NCAA.

Penalties are strict for failing an NCAA drug test for performance-enhancing drugs or street drugs. An automatic yearlong suspension is issued for the first positive test. A second positive test for street drugs results in another year of suspension while failing a test for performance-enhancing drugs results in permanent ineligibility.

But what are the chances the NCAA actually has success with such a small sample size? If a school doesn’t make an NCAA championship, the NCAA might not even test a single one of its athletes.

So LSU’s drug-testing policy has to be better than that, right? Not necessarily.

Simply put, LSU has a “three strikes, you’re out” policy when it comes to drug testing.

A first violation results in a slap on the wrist, a second yields a suspension from 15 percent of competition in the athlete’s particular sport and the third gets a one-year suspension from competition.

So the question isn’t whether Mathieu failed more than 10 drug tests, but if he failed more than three.

Whether he passed four, eight, 12 or 24 is irrelevant. According to LSU’s drug-testing policy, he should have been suspended for an entire season if he tested positive more than three times.

But it doesn’t surprise me he was able to continue taking what he wanted on the gridiron. Let’s not forget Mathieu was not technically suspended from LSU along with Spencer Ware and Tharold Simon against Auburn in 2011 — the trio was merely “withheld from play.”

Mathieu was the golden child during LSU’s undefeated regular season in 2011. The Tigers wouldn’t have gotten a chance to be humiliated in the BCS Championship by Alabama without the Honey Badger.

LSU doesn’t have to answer to anyone but itself when it comes to drug policies. It puts the policies in place, and it alone is responsible for following them.

Something needs to change.

Micah Bedard is a 22-year-old history senior from Houma.