Juan Melendez spent 17 years, eight months and one day on death row for a crime he didn’t commit.

He battled a language barrier, suicide and a system he says failed him in the end.

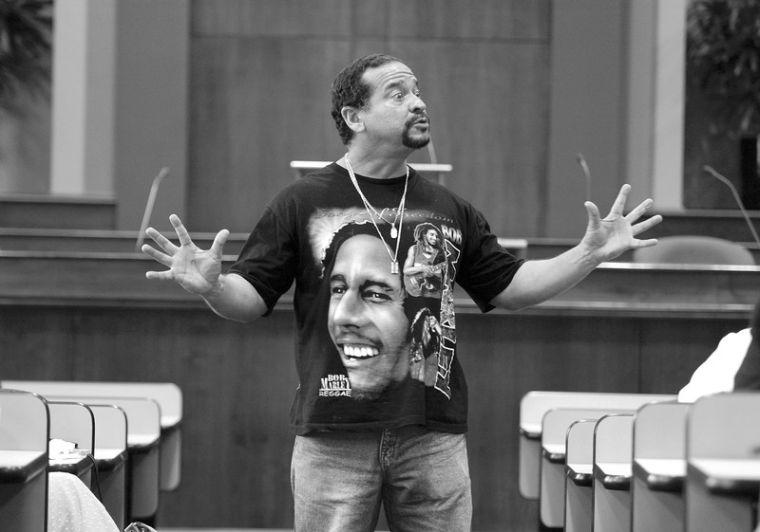

Dressed in a Bob Marley T-shirt and wearing a gold image of the Virgin Mary around his neck, Melendez spoke to students at the Paul M. Hebert Law Center on Tuesday about his experience and why he thinks the death penalty should be abolished.

Melendez was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in 1984.

After he was exonerated in 2002 Melendez began traveling the country, speaking out against the death penalty and telling his story and he hopes to inspire others to take up the fight against what he calls a racist and prejudicial system.

He also works in Florida, where he served his term, and across the country to promote legislation that would decrease prosecutorial immunity and provide financial compensation for the wrongfully convicted.

Melendez, who said he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, speaks out for inmates and the wrongfully convicted.

“Just like we got rid of segregation, just like we got rid of slavery, we can rid of this killing,” Melendez said.

Melendez called the death penalty a flawed system that can never be correctly reformed.

Judi Caruso, an attorney who formed Voices for Justice with Melendez, said legislatures should begin assessing problems with the death penalty within their states.

Caruso said she thinks states will find the system is not reformable.

“No matter how many reforms we do, we cannot reform, we cannot reform a system that could execute an innocent man,” she said.

Melendez, who was born in Brooklyn and raised in Puerto Rico, was arrested in 1984 while he worked as a migrant field hand in Pennsylvania.

Melendez said he will never forget that day: Monday, May 2, 1984. He was picking apples and peaches on a farm a few months after leaving Florida.

Federal agents identified Melendez, arrested him and extradited him to Florida.

Since he grew up in Puerto Rico, Melendez said his only language was Spanish.

“Imagine yourself in a courtroom, and you’ve been wrongfully accused, and you have no idea what they’re saying,” Melendez said. “If I spoke five words of English, three of them were curse words.”

He said he had a court-appointed attorney. Jury selections began on a Monday, and he was sentenced by Friday.

Melendez said after he was convicted, his “heart was full of hate,” and he became severely depressed and contemplated suicide.

Melendez talked about how easy it would have been for him to commit suicide and how other inmates sometimes encouraged it.

“‘You said you didn’t do it, they don’t believe you, they’re going to kill you anyways,'” Melendez said of the advice he received from other inmates. “After 10 years, I was tired of it, and the only way out was to commit suicide, and many of my friends did commit suicide.”

For the price of four postage stamps, a non-death row inmate would sneak in garbage bags, which could be fastened into nooses, he said.

But Melendez didn’t use the noose he received to kill himself – instead he said he found comfort in his dreams of freedom and his religion.

Melendez said his mother wrote him a letter that said she prayed five rosaries a day and put her trust in God that one day he would be free again.

It was the encouragement of his mother and his own faith, he said, that kept him going the last seven years.

The other inmates on death row taught Melendez how to read, write and speak English.

After three appeals, he received a new attorney, the miracle for which Melendez said he prayed and waited.

The new attorney discovered that the court-appointed defense attorney had received a taped confession for the murder by another person a month before the trial but had never introduced it in court.

Further investigation found that the prosecutor not only had the confession, but he also had 16 corroborating statements.

Melendez said the other miracle that saved him from death row was that the attorney who represented him in the first trial had now become a judge, creating a “conflict of interest.”

The trial had to be moved to another county.

The new judge issued a statement after reviewing the evidence, accusing the defense and prosecuting attorneys of misconduct and ordering a new trial, Melendez said.

The prosecutor then decided not to pursue a second trial, and Melendez was released in January 2002.

Melendez, who returned to live with his mother in Puerto Rico after his release, said he now works on a plantain farm with high-risk children.

Melendez said he teaches the teenagers how to grow plantains organically, tells them his story and hopes he will be able to set them straight before they get into trouble.

“I survived on the inside,” he said. “If I put my faith in God, I’ll be able to survive on the outside.”

Contact Ginger Gibson at ggibson@lsureveille.com

Free at Last

March 29, 2006

LUCAS HALEY / The Daily Reveille Juan Melendez, exonerated in 2002 after serving 17 years on death row, speaks to LSU law students Tuesday afternoon in the McKernan Auditorium in the Old Law Building. Melendez said he hoped to offer law students a new

Free at Last