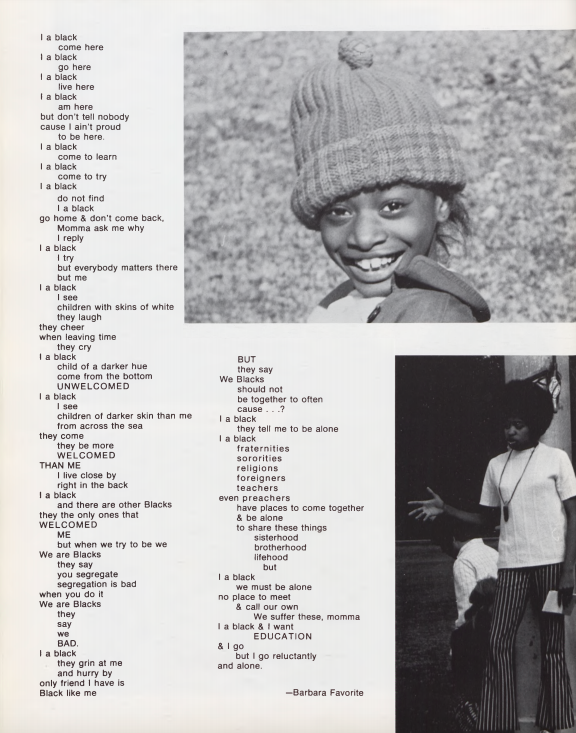

Barbara Favorite was a University student like any other — she walked around the quad, attended classes and earned her degree. In 1971, the year of her graduation, she published a poem in Gumbo Yearbook recalling her time at the University.

“I a black / we must be alone / no place to meet & call our our own,” Favorite wrote. “I a black & I want EDUCATION / & I go / but I go reluctantly and alone.”

Favorite, one of the few black students to attend the University at the time, wrote about her isolation from other students on campus. In 1971, there were no on-campus black student organizations and nearly no black professors. It wasn’t until 1972 when the Harambeé House opened, marking the first space dedicated to black students.

During Black History Month, the University looks to its past, present and future of diversity and equal opportunity on campus. Remembering “the good, the bad and sometimes the awful ugly” isn’t easy, but it’s necessary, said Dereck J. Rovaris, Vice Provost for Diversity and Chief Diversity Officer.

The University initially tried to desegregate in 1953 when Alexander P. Tureaud Jr. became the school’s first black undergraduate student. However, he was not allowed to finish his first semester, and it wasn’t until 1964 when the first group of six black students enrolled at the University. Freya Anderson Rivers, the first black woman to enroll, described her experiences in her 2012 book “Swallowed Tears: A Memoir.”

“The city ignited the cancerous pain of hatred that was enveloping me and destroying my life,” Rivers wrote. “At some point, I had to face this pain and the people of Baton Rouge to exorcise that demon. I could not recall the summer of desegregation without clenching my teeth and tightening my jaws, which caused a severe sharp lightning strike in my head that started a feeling of nausea.”

Rivers’ experience shows a darker side of Baton Rouge and the University’s history. However, the school has come a long way in the 55 years since Rivers first walked on campus. Now, there are more diverse students and on-campus organizations than ever before.

The University saw an increase in minority student enrollment from 21.6 percent of freshmen in 2017 and 30.9 percent of freshmen in 2018. Just nine years ago, minority students only made up 16.7 percent of undergraduate students and 13.5 percent of graduate students, according to the Office of Diversity’s 2009-10 Annual Diversity Report.

Rovaris, who worked at the historically black Xavier University before coming to the University, said LSU not only welcomes diversity but supports and celebrates it. The first step is getting students to enroll here, but the goal is to make them feel like they are just a student — not a minority student.

“Diversity is being invited to the dance. Inclusion is being asked to dance when you get there,” Rovaris said. “We’re asking students to dance now. We’re making sure they’re included in all kinds of ways, large and small. Recent history has included underrepresented students on the basketball court and football field, but now we’re in all kinds of walks of life.”

The Office of Diversity, first established as the Campus Diversity sector in 1999, has worked to increase inclusion and diversity support around the University. In addition to recruiting more minority students, the office created an opportunity hire program to increase diversity in the faculty. A lack of minority faculty members is still a big issue on campus, Rovaris said.

Rovaris and his team work with the Office of Human Resource Management to do “faculty search training,” which teaches departments how to increase the hire pool in terms of diversity. It’s a challenge, Rovaris said, but the office is focused on being more intentional about faculty recruiting efforts.

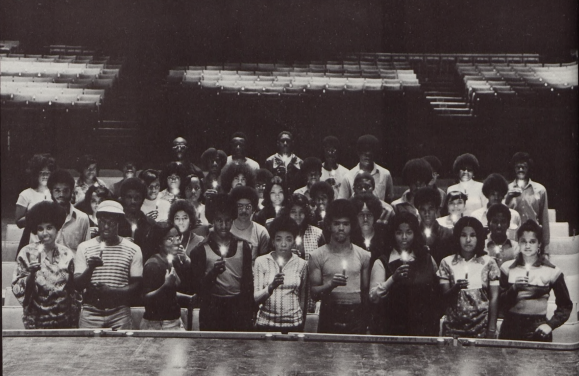

While administrators work to increase faculty diversity, students work to better the school themselves. Now more than ever, students are fostering an environment geared toward supporting people of color in the professional world.

People of color go through a different experience in the workplace than their white peers, said management senior Kendall Calvin, who is the treasurer of the Minority Business Student Association and the social media co-chair of Minority Women’s Movement LSU. She said it’s important to have a space for all minority students, not just for students of a particular race or ethnicity.

“We wanted to make a space to get professional development opportunities where we could talk about issues that affect minority business professionals when they leave college, when they get these full-time offers and when they’re really sitting within the real world,” Calvin said.

While having specific organizations geared toward minority students shows progress, it’s also important to have a diverse population in all parts of campus life, said Student Government president Stewart Lockett. Even SG, which Lockett said used to comprise of predominately white males in Greek Life, now has more minority student involvement than even a few years ago.

“Andrew Mahtook, who was Study Body President when I was a freshman, started the Department of Diversity within Student Government,” Lockett said. “We saw a very big cultural change. When he did that, it opened the door for other people to come in. Just four years later and Student Government looks very different, diverse and inclusive. I think it’s only going to grow.”

None of this progress would be possible without the men and women who attended the University when most people were against them, Lockett said. Nothing matches the bravery and hard work of the minority students who paved a way for the students of the future.

Barbara Favorite’s poem has been unknown for nearly 50 years — she was just another black student at the University. During Black History Month, it’s important to remember that progress does not exist within a single month, Calvin said. It’s about making sure that no student feels reluctant and alone at LSU.

“It’s important for us to know that history and that struggle to understand how far along we’ve come from where the University was at its beginning,” Calvin said. “But it’s also to pay homage and respect to those who had to go through a lot more difficult circumstances than we have, and making sure we understand that none of this is over yet — it’s just starting.”