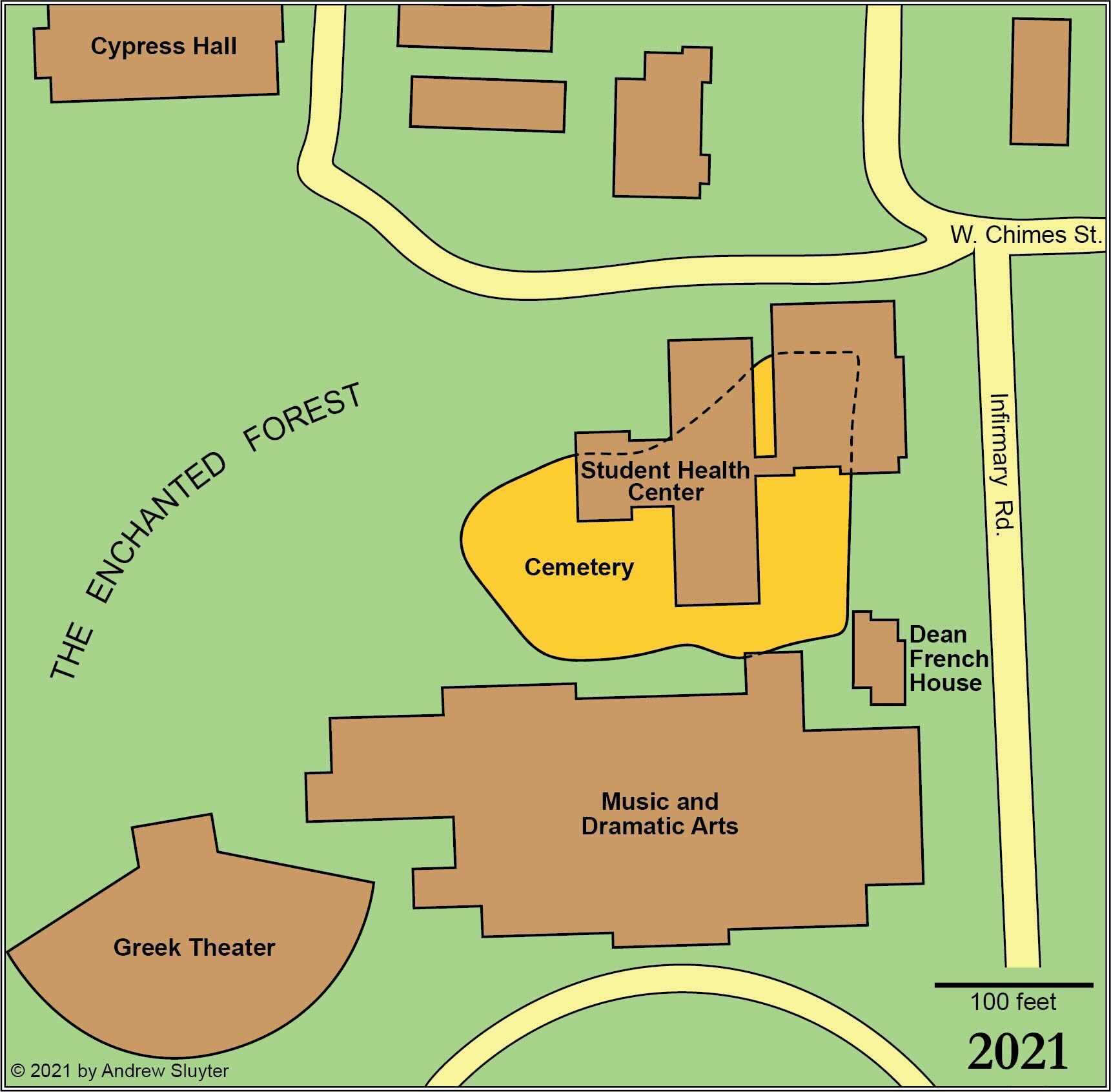

The university’s Student Health Center (SHC) was built atop a cemetery for enslaved plantation workers, according to an LSU professor.

Geography professor Andrew Sluyter has been conducting geographical research at the university for years, and with that has come a vast knowledge of the campus’ history. So when reports of slave cemeteries on campuses of multiple southern universities materialized, Slutyer theorized that the same could be true on the Baton Rouge campus.

“I was reading through newspaper articles about different universities in the South finding these old slave cemeteries on their campus,” Sluyter said. “So, I started looking at the old maps, and sure enough there was a slave cemetery right on the edge of what would become LSU property.”

Sluyter established the existence of the cemetery by reviewing century old documents from surveyors who worked with architects after the university’s purchase of the current campus grounds in 1918.

“When the surveyors surveyed this in 1921, it was right after LSU bought it and they wanted a survey of the campus before they decided what to build here,” Sluyter said. “And that’s the outline of the cemetery that he drew.”

The university purchased the site for the current campus from the Gartness plantation in 1918 and construction started in 1922, however it wouldn’t be until 1932 that the university was completely moved from the previous downtown campus.

As the student body population rapidly increased in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, the university deemed necessary to construct a university hospital, which is now known as the Student Health Center.

“In 1938 they started building the Student Health Center,” Sluyter said. “And in June when they put the first shovels to the ground, they found a bunch of graves.”

Sluyter had an undergraduate intern, Sarah Seivold, work for him by looking through Hill Memorial Library to look through all the editions of The Reveille from the 20’s and 30’s to find any mention of the cemetery.

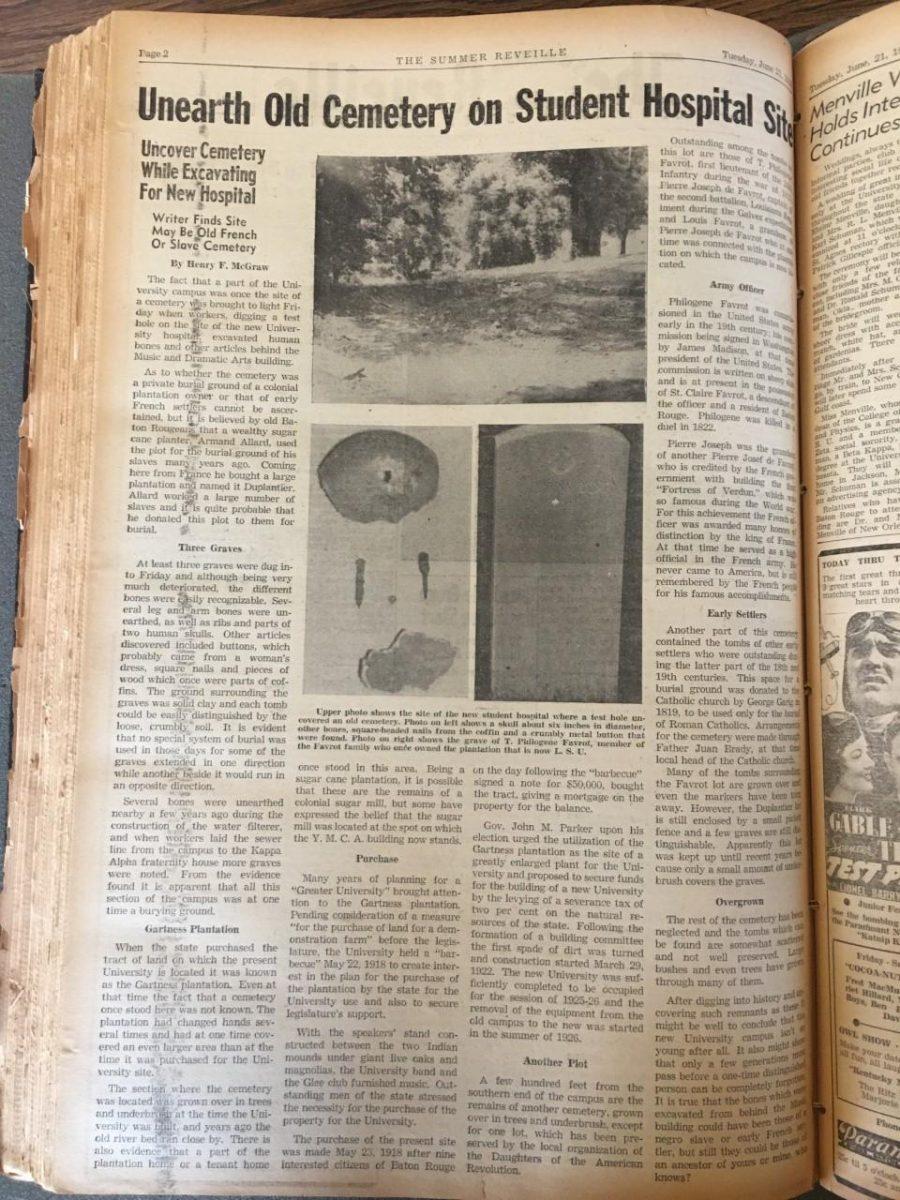

“At the very end, like on the last week, we found an article that talked about unearthed bodies here,” Seivold said.

The Reveille covered the discovery in a late June 1938 summer edition, documenting when university workers digging a test hole at the site of the current Student Health Center found human remains. The workers dug into three separate graves and discovered several bones and parts of two human skulls.

At any given point in the plantation’s history there would have been 50 to 100 slaves working, according to Sluyter.

While there is no way to identify the bodies discovered in 1938 or any others that were buried in the cemetery, Sluyter strongly believes the evidence suggests the cemetery was used to bury slaves.

“Of course, there’s no exact way of knowing who is buried here for sure,” Sluyter said. ““But we do know that all the owners of Magnolia Mound Plantation and this plantation were buried at Highland Cemetery.”

After the workers discovered the human remains in 1938 and photos were taken for The Reveille, there is no documentation of what happened to the remains. The loss of these alongside the lack of documentation for the burial grounds of slaves means Sluyter can’t definitively pinpoint when these graves were originally dug.

“The graves could date to any time between 1770 and 1918,” Sluyter said. “There’s no way of knowing.”