Behind every strong female coach is a long battle she fought to better women’s athletics for those who follow.

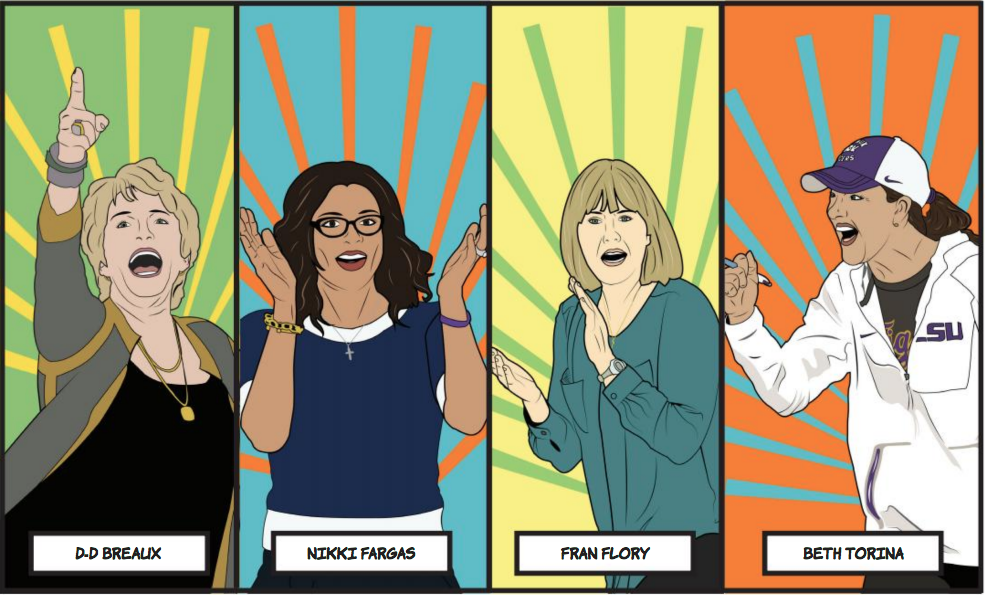

The women of LSU athletics have left lasting impressions on Baton Rouge, whether it has been for 40 years like gymnastics coach D-D Breaux, 20 years like volleyball coach Fran Flory or only six like basketball coach Nikki Fargas and softball coach Beth Torina.

In an industry that is dominated by men, these four LSU women coaches have learned to stick together and create lifelong friendships.

“It’s a very unified front,” Breaux said. “It’s a lot of inner support among us.”

Breaux, Flory, Fargas and Torina have each faced their fair share of struggles and battles, but they all agree that women’s athletics are still on the rise and stress the importance of having each other’s support.

Between the four women, there are 57 NCAA tournament appearances in their respective sports. The group of women at LSU are special because of the standard they uphold in their programs.

“The pioneers that fought for [us] and the growth that has occurred from their fighting, it has really been fun to be a part of,” Flory said. “I can only imagine how much further can we go.”

THE TRAILBLAZER

Fargas calls D-D Breaux the “Pat Summitt of gymnastics.”

Breaux has led the charge of women’s sports at LSU since the inception of LSU gymnastics in 1978.

Breaux was hired in 1977 to train the women’s club gymnastics team. However, Breaux’s women didn’t have scholarships, an official training facility or even a locker room.

What they did have when the women’s team first officially competed in 1978 was a small corner of the Field House, where they would set up and break down their own equipment to train.

They shared a locker room with the general population and often had to give up training time to football on rainy days.

It was a start.

Getting a fledgling program off the ground, especially a women’s program, wasn’t without a few bumps in the road.

When LSU Athletics underwent budgetary problems in the early ‘80s, the first to be punished was women’s athletics. According to Flory, Breaux wasn’t going to let then-athletic director Paul Dietzel drop the program she poured her life into.

And she didn’t. She fought that battle for weeks and eventually won.

Breaux has single-handedly built the gymnastics program from the ground up. She has established and maintained a program of excellence and helped grow gymnastics locally and nationally.

She went from handing out free tickets outside of Winn-Dixie to having them be a sponsor for the program.

“She’s seen it grow from basically when she had to beg people to come inside and watch,” said senior gymnast Myia Hambrick. “Now we have people begging to come inside and watch.”

The PMAC during a gymnastics meet presents an atmosphere that rivals the likes of Tiger Stadium and Alex Box Stadium. LSU has averaged over 10,000 fans for the past five gymnastics seasons.

“When I sit in the PMAC and watch her sport, I just can’t imagine an atmosphere like that anywhere else,” Torina said. “She has truly scratched and clawed and fought for that, and just what a mentor and model she’s been.

Called the “Dean of Coaches,” Breaux’s 40-year resume has set the standard for the other female coaches on campus. She turned LSU into one of the most successful gymnastics programs in the country.

“When I think about her sleeping in a tent to sell tickets or doing the things that she used to do, we’re so fortunate to be where we are now because of people like her,” Torina said.

None of the program’s success, both on and off the floor, comes as a surprise to Breaux.

“You don’t come into work every day thinking ‘Oh it’s okay if I’m just average,’” Breaux said. “There were a lot of battles and a lot of anger and emotions. I think it was worth every battle.”

THE SHIFT

When she would go on recruiting visits, it was commonplace for Flory to see just mothers and daughters at volleyball matches.

About a decade ago, she noticed a new group of spectators at the games: the fathers.

“The biggest influence in this whole process is the men that grew up with women’s sports in existence now value women’s sports for their daughters,” Flory said.

Flory said that as the dads became more involved, the support for the sport overall grew as well.

As women’s athletics began their uphill battle when Title IX was passed in 1972, Flory referred to it as a ‘necessary evil’ because schools were forced to equalize men and women’s sports at the time.

LSU athletics promoted volleyball, women’s basketball and gymnastics to varsity sports in 1977-78 to comply with the Title IX laws.

“The hard thing during that time was the fact that everything that the women got, the men resented,” Breaux said. “[The men] felt like we were taking it away from them. I never saw that. I never felt like they took something away from the men’s gym program so that the women’s team could have something. They never lost anything.”

While Breaux built a gymnastics empire from nothing, Flory was also in a position where her volleyball program still needed change.

Flory remembers when she would have to drive her own car to tournaments and games, and now the team takes a charter plane to away games.

“I look back, and the difference in kids today is that we were honored, and we would have given anything just for the chance [to play],” Flory said. “The kids today — not all of them — but they think they deserve the chance. They don’t know how hard people fought to get this chance.”

During her time as a student-athlete, Flory played in the first NCAA national championship women’s volleyball game, was part of the last AIAW national championship team and even started the basketball program at her high school.

Through more than 20 years of coaching, one of the biggest changes Flory has seen during her time is the respect and recognition of the program.

“The evolution of women in sports is what I find really fascinating,” Flory said. “Today, it’s respected and it’s honored and there’s some prestige to it. Back when we all started, women didn’t have these opportunities.”

In a head coaching position, the women coaches help run and are part of a multi-million dollar company when it comes to scholarships, travel expenses, revenue and more.

In college athletics alone, the NCAA made $1 billion in revenue for the first time and the LSU athletic department generated more than $147.7 million in 2017.

“Now, the door is opened and because it’s become a business,” Flory said. “We’ve all become business women.”

Unlike Breaux and Flory, Torina and Fargas are building programs that were established by powerful women before them.

Former softball coach Yvette Girouard is well-known in the community for building up softball at LSU and at Southwest Louisiana and then expanding it outside the state.

“She’s done so many things just to pave the way so that when I got here, it was smooth sailing from the groundwork she laid for us,” Torina said.

And before Fargas, there was Sue Gunter.

Gunter coached LSU women’s basketball for 22 years, and in 2005 was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. She is widely remembered for being a pioneer of the game and one of the greatest women’s basketball coaches in history.

“We don’t want to come and be gone,” Breaux said. “We want our programs to sustain us. Yvette wanted her program to sustain her. You just know that [Girouard] feels a part of the success that [LSU softball is] continuing to have.

“I feel the same way about going to women’s basketball, and I know the price that Sue Gunter and Pokey Chatman paid and the hard work that they did to build that program with Sylvia Fowles and Seimone Augustus,” Breaux said. “I go to women’s basketball games and I know that Nikki feels like those days are going to come back.”

MOVING FORWARD

Before 1972, women couldn’t run the Boston Marathon, get a credit card and struggled to get a divorce.

When Title IX was passed in 1972, opportunities for women increased. It started with being teachers and nurses, and it slowly inched closer to equality.

“We’re already there, and we’re growing it,” Torina said. “We have a product that people want to see. We’ve got to keep playing the game the right way.”

Women’s sports are now nationally broadcasted daily. The Women’s College World Series and the Women’s Final Four are two of the largest programs every year. The SEC Network puts on “Friday Night Heights” every week to showcase the gymnastics programs across the nations.

Through all of this development, Fargas emphasizes that there are so many more stories to be told in women’s sports, and there is so much further to go.

Outside sources like television broadcasts have done so much to assist in the growth of women’s sports across the nation, but that fight from within is never over.

It goes far beyond the games they play.

“I feel the responsibility to be a guardian of the game and make sure that we’re doing all that we can to promote women in a positive way,” Fargas said. “The sportsmanship you see on the court, the way we carry ourselves in the classroom, how involved we are in the community — we all have to take on that responsibility.”

Many women have made sacrifices to get them where they are today, and they want to make sure the world understands what those sacrifices have meant.

The changes are stark, from the differences in facilities and arenas to simply fan appreciation and attendance.

Flory urges young people in the industry to never feel like any job is too small for them. Whether it’s cleaning or assisting, every part of a program is important, and those running it must be multi-faceted enough to take that role on.

“You have to be a visionary,” Flory said. “You can’t be satisfied sitting and waiting for somebody to tell you, ‘Here’s the next step.’ All of us that came from that era have to see what potential is out there and quite often we have to be the ones to create it. You can’t wait for the help. We never have.”