One of the best films of the year, “City of God” tells a harrowing story of gangs, poverty and corruption in Brazil’s capital. The film’s title is a slang term Rio de Janeiro residents use to describe their city. By film’s end, it feels like God has pulled out of his city and denounced it as another Sodom or Gomorrah.

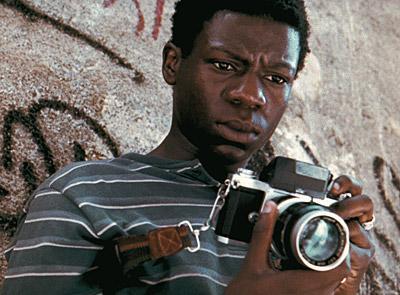

The film begins in a whirlwind: A group of young men chase a chicken through a Rio de Janeiro slum, laughing and pointing their handguns at it. Rocket (Alexandre Rodrigues), a teen-age native of the slums, finds himself in the middle of a street as the group rushes toward the chicken. He turns around, and behind him stands a group of police officers, their handguns raised. Upon seeing the police, gang members immediately draw every weapon they own.

At this point Rocket the narrator steps in, and says in order to explain his current situation he must tell of his past.

The past he describes for the rest of the film exudes pathos. In Rio slums dominate the inner-city landscape. Gang culture thrives on the stump of poverty, and as every citizen of the slum is poor, every citizen of the slum seems to engage in crime. Drug-dealing gang leaders Carrott (Matheus Nachtergaele) and Li’l Ze (Firmino da Hora) control most of the drug trade, and as their power grows, the conflict between them begins to boil. Bodies pile up, and Rocket, one of the few who escaped the gang life, has a strange but important perspective. He watches everyone he knows fall prey to the ruthlessness of gang mentality.

Freshman director Fernando Meirelles integrates disturbingly realistic violence into his film. Images of the true Rio permeate the story, portraying the city as a rotting slum festering with gangs which thrive off drugs and indiscriminate murder. Rival gang members’ lives are worthless, and innocent people’s deaths in heists mean nothing. In the City of God, killing is a way of living.

Meirelles accomplished some of the movie’s realism by using local Rio actors and real slum kids to play his characters. It works, and the actors look the part.

Employing creative cinematic techniques, Meirelles tells most of his story visually. His camera appropriately bounces and twirls along as it follows the winding paths of the story’s characters. They never are still, so why should the camera ever stay still? One virtuoso sequence involves a strobe light, a nightclub and staccato editing. The result is one of the most powerful and intense scenes in the film, pulsating with a concentrated, ferocious energy seen in perfect moderation through the rest of the story.

Many have compared “City of God” to “Goodfellas.” The key difference between to two lies in situation: The “Goodfellas” gangsters live their life as they do because they want to. The characters in “City of God” live their lives as they do because they must to survive. The movie pulls no punches in its storytelling, and each scene is as important as the next. Through a brilliant story, fiery characters and striking technique, “City of God” simply tells it as it is.

Gangs, corruption live in ‘City of God’

April 7, 2003

Gangs, corruption live in ‘City of God’