When most people hear the words “bus boycott,” they think of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr. or Montgomery, Ala. Few people think of Baton Rouge.

But several people say the mid-20th century bus boycotts, which were part of the Civil Rights Movement, started in Baton Rouge.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Baton Rouge bus boycott.

In the early 1950s, hundreds of African Americans in Baton Rouge rode the city buses downtown to go to work. Willis Reed, the publisher of the Baton Rouge Post — a paper covering the activities and concerns of the city’s African-American community — said blacks made up more than 80 percent of the bus system’s riders, and public transportation was the only way for many of them to get to work.

At this time, African Americans were not allowed to sit in the front of the bus. The bus system reserved the first 10 seats for whites, whether they were filled or not.

In January 1953, the city-parish council raised bus fare from 10 cents to 15 cents. Reed said many blacks did not want to pay the higher fare when they did not have the freedom to sit where they pleased.

“I started organizing a group to do something about it,” Reed said.

Reed and several others began organizing meetings, which were attended widely by blacks living in the area just north of the University.

Organizers asked Rev. T. J. Jemison of Mt. Zion Baptist Church to speak at their meetings.

Mary Price, director of LSU’s Harry T. Williams Oral History Center, said Jemison went a step further by going to the city-parish council meeting and publicly denouncing the fare increase and reserved seating.

On Feb. 25, 1953, the city council approved Ordinance 222, which gave blacks permission to fill the bus from back to front and whites the liberty to board from front to back.

Ordinance 222 went into effect in March but many bus drivers ignored it completely, Price said. The law was not enforced.

On June 13, Jemison tested the law by sitting in the front seat of a bus, carrying a copy of Ordinance 222 in his pocket.

The bus driver ordered Jemison to move. When he refused, the driver drove to the police station. The officer who boarded the bus sided with Jemison and made no arrests.

On June 15, after several other incidences similar to Jemison’s refusal to move, Baton Rouge bus drivers began a four-day strike to protest Ordinance 222.

Price said drivers went back to work four days later, after the state attorney general declared the law unconstitutional because it violated the segregation laws at the time.

On the same day bus drivers went back to work, Reed and other organizers sent Jemison and Raymond Scott, a black tailor, to WLCS, a local radio station.

Scott announced on the air they would begin a boycott of the city bus system the next morning and urged all blacks to stay off the buses.

“The next morning, the whole city was thrown into an uproar,” Reed said. “That was the first time in the U.S. this had happened.”

Price said boycott organizers promised all blacks who stayed off the buses a free ride to work.

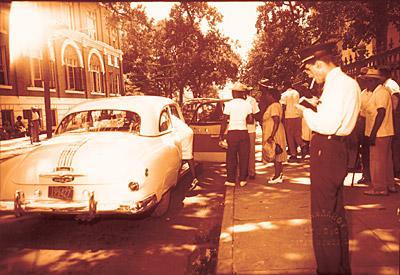

The Free Ride System organized several black people who owned cars and arranged for them to pick up people who agreed to boycott.

Each night of the boycott, organizers held widely attended meetings in which they discussed the unfairness of the segregation laws and the purpose of the boycott, Reed said.

Organizers held the first mass meeting at Jemison’s church and the second at McKinley High School, which was an all-black school at the time. Because of the large crowds in attendance, the third meeting was held at Memorial Stadium.

While the official boycott lasted until June 23, many protesters still refused to ride the buses.

On June 24, the city council passed Ordinance 251, which was viewed as a compromise, Price said. The new law reserved the first two seats on the bus for white people and the last two seats for African-Americans. People of any race could fill the seats in between.

The Baton Rouge bus boycott had a large impact on both the Louisiana segregation laws and the American Civil Rights Movement.

“It’s hard for people today to understand all this, whether they’re white or black,” Reed said. “We’ve come a long way.”

Although it is not confirmed, many people say Jemison helped advise Martin Luther King Jr. when he was dealing with the Montgomery boycotts, Price said.

“Knowing that Jemison and his associates had set up an effective private carpool, I put in a long-distance call to ask him for suggestions for a similar pool in Montgomery,” said King, in his book “Stride Toward Freedom.” “As I expected, his painstaking description of the Baton Rouge experience was invaluable.”

Price explained the boycott did not affect the University strongly at the time because black students were not allowed to enroll until several years later. LSU since has recognized the significance of these events.

Price became interested in the boycott while working on her graduate thesis about the history of African Americans at LSU and in Baton Rouge. She continued her research when she began working in 1991 for the Williams Center, which is a branch of LSU Libraries designated for researching the history of the University and the city.

The 1953 Baton Rouge bus boycott is significant in both American and local history because it helped set the framework for the entire Civil Rights Movement, Price said.

Price pointed out the boycott also is important because some of the issues these events brought to attention still have yet to be resolved. The main issue of the boycott was the desegregation of the bus system, and the desegregation of Louisiana’s public schools still is an issue today.

Because of the importance of the boycott to the community and the country, the University is hosting a conference at the Lod Cook Alumni Center to honor the anniversary on the weekend of June 19.

Several professors and teachers from the University community and around the world are planning to attend the conference.

Price said one of the main focuses of the conference will be teaching the professors and teachers in attendance how to incorporate the Civil Rights Movement into the classroom.

Beginning the Boycotts

February 19, 2003

Beginning the Boycotts