Tiger Stadium is built not just of concrete and steel but of the devotion and tradition of one of sports defining fanbases. It holds over 100,000 fans and ranks in the top 10 largest U.S. stadiums but now it also holds a century of memories and relationships built around football

This week, LSU celebrates the centennial of Death Valley, a place with a heartbeat as strong as an earthquake. It’s known for the gridiron titans that clash on the field, but its true trademark lies in a folklore of dedication and community.

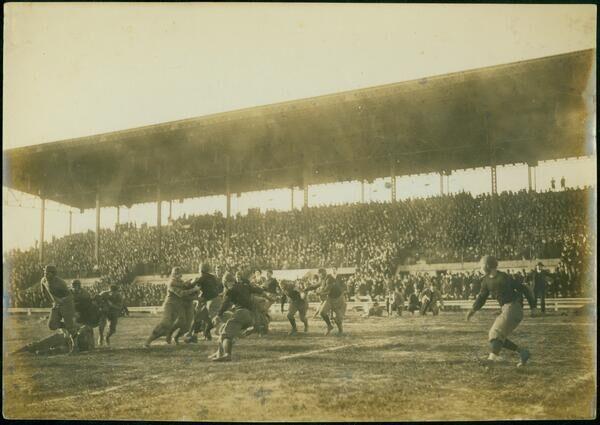

Former Louisiana governor Huey Long obtained the initial funding for the stadium’s construction by labeling it as student housing — which it was, just with the size, shape and functionality of a football arena.

Originally in a horseshoe shape, its barracks housed hundreds of students, none of which had air conditioning. While free attendance to games was not granted, sneaking in through dorm windows was not an uncommon maneuver.

The colossal stadium is much different today. The game day experience back then is also unrecognizable to modern day.

The early years

Mike Nola, a lifelong LSU fan, recalls attending games with his father in the early ‘50s. They would watch through hedges on the south side of the stadium before getting in free after halftime.

“A ticket was a dollar, maybe less,” Nola said. “He wasn’t gonna pay that.”

To maintain free entry years later, Nola got a job selling Coke bottles at the game. He’d make around $2.50 a shift with tips.

“Back in those days, after the game, fans could walk on the field,” he said. “I’d have a bunch of my buddies I sold drinks with, and we’d get chin straps.”

In this era, fans could walk right up to players and collect gear. Being the quickest, Nola was once able to obtain a chinstrap from Billy Cannon.

By the time he was in college, Nola no longer had to finesse his way into games, though even attending as a fan required formal attire.

“We wore a coat and tie,” he said. “The student section all brought a date.”

Nola recalls all freshman boys and girls lining up on the Parade Grounds for orientation. They were told to walk in line across from each other and then stopped. Whoever was across from them became their date for the game.

These early years also saw Mike the Tiger wheeled out in his cage for every game day.

“They’d bring him around and cheerleaders would be on top of the cage,” Nola said. “They’d get in front of the student section, they’d bang on the cage, and he’d growl. It would fire up the crowd.”

As the stadium and game day experience evolved, so too did the football fanaticism. One night in particular, that fanaticism apexed.

The Earthquake Game

“All you could smell was bourbon and popcorn,” former LSU defensive lineman Karl Dunbar (1986-89) said. “You could see the smoke over the field and the fans going crazy. The mist from the bayou was starting to come over the stadium.”

It was 1988 and No. 4 Auburn was coming to town. It would amount to arguably the most famous game in Tiger Stadium history.

“That was probably the most physical game I’ve ever played in,” former LSU linebacker Eric Hill (1985-88) said. “That was not for the weak. There were some guys getting laid out and some guys delivering some hits. Anybody that played in that game came out of that game sore.”

After struggling to push the ball all game, LSU’s offense finally hit a rhythm in the fourth quarter. Then finally, less than two minutes on the clock, 4th-and-10 from the Auburn 11, down by six. It had to be now.

Quarterback Tommy Hodson dropped back and found running back Eddie Fuller in the back of the end zone. The overwhelming tension that had filled the stadium quickly detonated into a deafening roar.

“We’re just high-fiving and hugging because talking, you can’t hear each other,” Hill said. “It wasn’t like an explosion that settled down, the fans just kept going.”

The morning following the victory over Auburn, the Louisiana Geological Survey discovered something unbelievable. Activity registered on a seismograph was determined to have come from the eruption of the crowd after Fuller’s catch.

“It was almost like you’re walking along and there’s a stampede coming behind you,” former homecoming queen Renee Myer said. “It was that kind of energy.”

This game has remained a symbol of the scientifically unfathomable intensity one finds in Death Valley.

“Our stadium, it’s like it’s coming down on you,” former LSU linebacker Walter Moreham (1998-2001) said. “The whole stadium feels like a rabid student section.”

Tiger Stadium is perennially considered an epicenter of college football and among the most difficult environments to play in.

“The fans are everything that we desire to have as a player,” former LSU wide receiver Eddie Kennison (1993-95) said. “Hearing the roar of the crowd, that gives us that extra boost of energy.”

Hill considers the fan base responsible for a significant number of wins in the stadium.

“That energy that you pull from the fans, that’s different,” Hill said. “That is that premium additive that nobody gets a chance to get.”

The extremes of fanaticism

Just as strong as this undying intensity is the strength of community.

“They make you feel good about the choice that you made years ago,” Hill said. “Because you’re always welcome. You’re part of the family.”

Hill makes an effort every year to bring someone he knows to a game who has never been. Most recently he brought a coworker and his son.

“They are in awe. I mean jaw dropped on the ground,” Hill said. “I felt good, to be able to offer somebody something they’re so appreciate of.”

Wearing different colors in the stadium may be ill-advised, but the welcoming southern charm is on full display at tailgates across campus, even to opposing fans.

“We had a lot of UCLA people come over and just chat,” recent LSU graduate Caitlin Glancey said when the Tigers played the Bruins recently. “Just being very welcoming I think was something that surprised a lot of them.”

The scents of jambalaya, étouffée and gumbo combine with the smell of stale beer on what is for many a multiple-day affair.

“Those RVs start rolling in on Thursday,” Hill said. “So those tailgates, they get cranked up early. By Saturday night, they’re on the three-day drunk.”

As a player, after every game, Moreham would head straight for a certain tailgate that had a sourdough sandwich topped with gravy waiting for him. Once he became a graduate assistant, that came with a beer.

These rituals do not reschedule, deviate or surrender. Because what would a Louisiana Saturday night be without them?

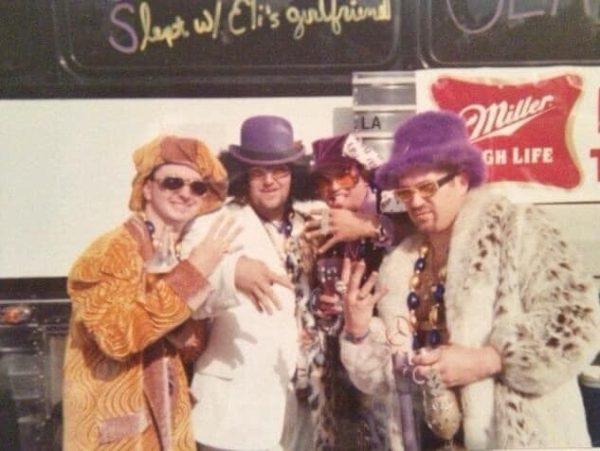

Just as often, this fanaticism makes its way from its designated tailgating spots to opposing stadiums. Like filling a coach bus with 40 LSU superfans in pimp attire.

On a trip to watch LSU play Virginia Tech in 2002, a years-long tradition was conceptualized.

Brian Rappold and a number of friends cruised in a Winnebago to a CD hip-hop mix labeled “Pimpin’ to Blacksburg.”

The natural progression, of course, was a six-season commitment to a yearly Pimp Nation migration.

Rappold made his suit out of Crown Royal bags, and another was made by a friend’s mother-in-law out of LSU bedsheets.

The ensemble included a mix of canes, fur coats, rings, glasses, capes and suspenders.

“Never taken more photos and had more paparazzi than when we did those trips,” Rappold said.

Eventually as Pimp Nation grew, the commute expanded into a coach bus. The ride featured drinking games, card games, pen-to-paper prop bets, yelling, booze and camaraderie.

On a trip to Starkville, the bus was stopped by a police officer.

After pulling him over, the cop asked the bus driver, “What do you got back there?” Unsure how else to say it, he replied, “I got like 40 pimps.”

After some complicated explaining, the officer escorted the bus to campus and proceeded to take photos with the group, including a few miming arrest.

Debbie Heroman, a lifelong fan and decades-long educator at LSU, inherited an allegiance to the purple and gold from her father, Billy Scruggs. Scruggs was so dedicated, he made nearly every game in a 63-year stretch.

She would call her father a “redhead” for his screams and frustration when watching games. Her family would tease that he was going to give himself a heart attack.

Their humor was prophetic.

“He had a heart attack in Tiger Stadium,” Heroman said. “He noticed but he wasn’t gonna leave the game.”

The friend he had come with suggested they leave, but Scruggs declined. He drove himself home, was taken to the emergency room and later underwent a bypass surgery.

Years after selling coke bottles and wearing a coat and tie to football games, Nola started a family. Raising a six-month-old baby kept he and his wife plenty occupied, but not enough to miss football.

In anticipation of what would become the historic 1972 “four-second game” against Ole Miss, Nola was eager for a ticket.

“We needed to go to this game,” Nola said. “Somebody offered us tickets; it was impossible to get a ticket.”

Because of the last-minute opportunity, he and his wife were left unsure of what to do with their baby. So, they found a creative solution.

“We looked at classified ads, found a lady in a trailer that was babysitting for the football game,” he said.

Prior to the game, the couple stopped by a trailer park and handed off their child to a stranger. All ended well, though Nola said he regrets taking such a risky decision.

Unsung heroes of game day

“No bored moments are to be permitted the spectators in the short periods of inactivity during a game,” then-LSU cheerleader W.B. Graham said in a 1924 issue of the Reveille. “Win or lose, it’s going to be one grand jubilee from start to finish.”

Today, this jubilee is characterized by Mike the Tiger, the Color Guard, cheerleaders and, of course, the band.

“The band is one of the hardest working groups I know,” Moreham said. “They stay out there later than we do.”

Former Mike the Tiger mascot Alex grew up in the shadow of Tiger Stadium and was among the longest-serving mascots in school history.

“Whether it’s football or even just outside events, LSU and Mike the Tiger just means so much to the local community that it really makes you emotional sometimes,” Alex said. “Being able to provide that kind of happiness, that kind of thrill to fans was one of the best parts of the job.”

On a game day, Alex would visit familiar faces at tailgates, take pictures with kids, march down Victory Hill and lead the team out the tunnel with fireworks around him and a giant flag in hand.

“No matter what the outcome is, no matter how it played out on the field,” Alex said. “I had to represent my school to the fullest. It’s very easy to do when things are going well, but no matter what, you got to get out there.”

Other SEC mascots fight to travel to the LSU game because they hear the stories and want to see it for themselves, Alex said.

Alex’s last game as Mike the Tiger ended in epic fashion.

“LSU scored a touchdown in the final seconds,” Alex said. “The player ran to the sideline and high-fived me. That was the very last play of my football career as Mike, and I’m like, ‘That’s as good as it gets.’”

Most games, cheerleaders wake up at 6 a.m. to do hair and makeup. Once they arrive, they warm up, do promotions, meet families, do pregame preparation, march down Victory Hill, warm up again and go onto the field for hours of physically demanding performance.

“I think it shows that we care a lot, and we really care with what we do,” current cheerleader Maggie Hawkins said. “That we’re 100% in with everything.”

Recently, the cheerleaders were asked to execute a newly introduced and sometimes dicey skill.

“Our coach had called for us to do the double-up pyramid,” she said. “Looking out into the fans and seeing that as encouragement and motivation… We ended up smacking it, it was one of our best double-ups we’ve ever done.”

Morgan Schooler, a current member of the Color Guard, shares this understanding of the commitment behind every game day.

“You don’t see all the hours that go into it,” Schooler said. “You don’t see the work, the tireless nights. We were coming up on close to 25 hours of practice last week.”

But for Schooler, it’s well worth it.

“When I’m on the field marching pregame and you hear the T-I-G-E-R spell out — it’s echoing, I can’t hear myself breathe, I can’t hear myself think,” Schooler said. “I get a glimpse of old me and I think, ‘I really made it.’”

Going from lifelong fan to playing a role in what makes LSU special can be an emotional experience.

“Going down the hill the first time, I was crying, and I didn’t even know it,” Schooler said. “I was like, ‘Why is this energy flowing through me right now?’ … If I could do this forever I would.”

In her first game with Color Guard, Schooler and LSU performed alongside McNeese. The performance was in response to Hurricane Ida for a “Louisiana Strong” show.

“I can impact the life of somebody else and they can choose to come here because of me,” Schooler said. “I think it’s so great being a part of something so much bigger than myself.”

Bigger than football

Mikaela Davenport, a former student and now Associate Extension Agent with LSU AgCenter, can credit LSU for some of the most significant moments in her life, specifically those with her husband Jerry.

The two met formally for the first time at a football game.

“He did a double take and I guess thought I was pretty cute,” Davenport said. “Which is nice after I’ve been sweating, tailgating and hooting and hollering all day.”

After about four years dating, just before graduation, he proposed.

“When he proposed to me, he proposed in front of the bell tower,” Davenport said. “So much of this campus and everything about the culture of LSU and LSU athletics has played a significant role in our relationship.”

That trend continued with a wedding that fell on a game day.

“My family growing up were huge LSU fans,” she said. “If you got married in the fall, you either got married around LSU football, or you had the game on at the reception.”

As promised, Davenport prepared for her big day with mimosas and football. She said it helped take her mind off the stress of it all.

“We decided to go with the plum roses and sunflowers,” she said. “I was adamant to say my colors were plum and sunflower, because otherwise everybody said my colors were purple and gold.”

As a result, many were inadvertently in LSU colors, including the best men and bridesmaids.

To keep with the trend, the couple had their child just before a game day.

Much like Davenport, Glancey had one of her relationship’s biggest moments in true LSU fashion.

Because her fiancé, Jacob, worked for the Tiger Athletic Foundation, he devised a plan to propose in the middle of Tiger Stadium.

After “just swinging by” the stadium to pick up some documents, the couple began a quick tour that ended on the grass. After deviating her attention, Jacob got down on one knee.

“It was kind of romantic in a way because it was still kind of drizzling,” Glancey said. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I’m on Tiger Stadium getting kissed in the rain like a Taylor Swift song.’”

In terms of total significance, few moments measure up to that of Myer. In 1991, at the 50-yard line, she was crowned the first black Homecoming Queen in LSU history.

“It’s heartwarming to know I’m considered a bit of a role model to some,” Myer said. “Especially in my daughter’s eyes.”

After being crowned, Myer walked over to her sorority sisters, where she was serenaded.

Myers’ victory came the same night as the 1991 election for governor between David Duke and Edwin Edwards. This context likely affected the reception of her trailblazing achievement.

“I did feel a little uncomfortable because there were some folks that weren’t happy about the fact that I was crowned,” Myer said.

Myer had heard rumors that in previous elections, when a black queen was nearly chosen, changes were made to the process to avoid it moving forward.

But Myer believes in and has witnessed the substantial change that has taken hold at the university since 1991.

“I think if you look around in the classroom and if you look around in leadership positions, you’ll see a lot more diversity there,” Myer said.

She did not realize until later the significance of her Homecoming victory, but as time went on, recognition mounted, and her perspective altered.

A.P. Tureaud, the first black student at LSU, developed a relationship with Myer.

“A.P. Tureaud was someone that I admired and looked up to,” Myer said. “Now to have him be a friend.”

Today, a portrait of sailboats with hints of pink and yellow sits in Myer’s office at LSU, painted by and gifted from Tureaud.

“That feeling as though you’re a part of something bigger than yourself,” Myer said. “It’s kind of a part of what you are when you’re a Tiger.”

To Myer, Tiger Stadium represents a part of LSU that is inclusive all the time.

The stadium means so many different things to so many different people.

Hill recalls his last moments there, while preparing for the NFL draft in January.

“I was stretching in the middle of Tiger Stadium,” he said. “That’s when it hit me that I’d never play another game in the stadium. I was by myself, that was emotional.”

Now every time he hits the Mississippi bridge coming into Baton Rouge, he always looks over to the right for Tiger Stadium.

“You hear the roar of the stadium, all of these people are here at the exact same moment in time, cheering for the same team,” Schooler said. “I think that’s really, really special.”

You can point to the H-style goal posts or the numerals every five yards to distinguish Tiger Stadium, but an arena that holds the hearts of fans across the globe and seizes a full day of their week has more character than that.

“This is the definition of home,” Glancey said. “It is quite literally where culture comes alive.”